HEAD AND NECK INJURIES IN FOOTBALL: MECHANISMS. TREATMENT, AND PREVENTION.

April 1974 THOMAS E. CLARKE '66HEAD AND NECK INJURIES IN FOOTBALL: MECHANISMS. TREATMENT, AND PREVENTION. THOMAS E. CLARKE '66 April 1974

By Richard C. Schneider '35 M.D. Baltimore: Williamsand Wilkins, 1973. 261 pp. $18.75.

One of the reasons football is so popular is that it is a rugged, at times violent, contact sport. Everyone accepts the cliche that "injuries are a part of the game." Unfortunately, included with minor bumps and bruises are the tragic head and neck injuries that result in death or permanent injury. Dr. Schneider reports that 96 percent of fatal gridiron injuries in 1966 were due to head and neck injuries and that there were 29 fatal neck and head injuries in 1970. While not condemning the sport, he points out as a fan and as a physician that something must be done to prevent more individuals and families from paying the ultimate price for mere sport.

Head and Neck Injuries aims to educate coach, physician, trainer, medical student, and specialist toward the reduction of such injuries. Dr. Schneider accomplishes his purpose in readable style, punctuated with case histories and action photographs. The more scientific material is in fine print, and a comprehensive bibliography is available for the physician.

The first section of the book is devoted to an understandable description of head and neck anatomy and classification of the craniocerebral injuries. Following is a chapter on Mechanisms of Injury which should be required reading for coaches, officials, and rules committees. Dr. Schneider suggests that the increased incidence of severe head and neck injuries may be due to ne exploitation of improved equipment. For instance, the sandlot player is less likely than his college counterpart, with a bigger and "better" helmet, to spear and stick-block, two practices which Dr. Schneider considers sufficiently dangerous to be outlawed.

Two chapters on the psycho-social aspects of [he game shed some insight on who plays football, who should not play and why, information that should help coaches in effective counseling 0f their squads. A chapter on first aid offers many useful suggestions. Having a bolt cutter available to remove the face mask to gain access to the airway, for example, prevents the necessiry removing the helmet so the cervical spine is not jeopardized.

The final chapters of the book, devoted to the development of experimental models to evaluate mechanisms of injury and equipment improments, were of special interest to us at the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital. Dr. Michael Mayor of the orthopedic section, who helped with this review, and Dr. Ernest Sachs of the neurological section are currently investigating the abrupt rise in head and neck injuries from skiing. Like Dr. Schneider, they are trying to develop more effective head gear.

Whenever an orthopedist and a neurosurgeon discuss a common problem, there are apt to be slight differences in emphasis. We would have liked to see more on the role of neck musculature in preventing cervical spine injuries and the effect of trauma on the soft tissues. These and other criticisms are minor, however, compared with the enormous contribution Dr. Schneider has made.

This book is not just for physicians. It belongs also in coaches' and trainers' libraries, alongside You Have To Pay the Price by Blaik and Cohane. Only through a sane balance of opinion can we achieve improvements for, in Dr. Schneider's words, "our favorite national sport, football."

Dr. Clarke, currently a resident in orthopedicsin Hanover, has an intimate working knowledgeof both viewpoints toward the subject of thisbook. He will be well remembered as the captainof Dartmouth's 1965 undefeated, Ivy Leaguechampionship football team which won theLambert Trophy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTomorrow: A Call for Limited Growth

April 1974 By DENNIS L. MEADOWS -

Feature

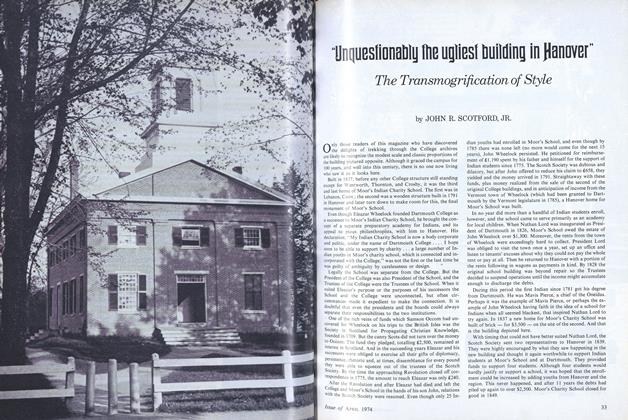

FeatureUnquestionably the ugliest Building in Hanover"

April 1974 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD, JR -

Feature

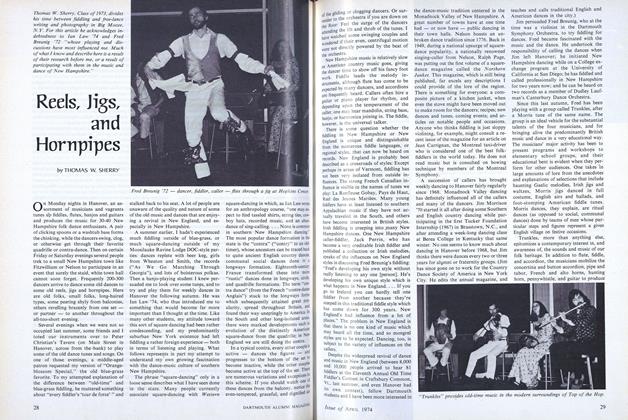

FeatureReels, Jigs, and Hornpipes

April 1974 By THOMAS W. SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureYesterday: A Policy of Consumption

April 1974 By GORDON J. F. MacDONALD -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR. -

Feature

FeaturePoseurs, Impostors, and Scalawags

April 1974 By MARY BISHOP ROSS

Books

-

Books

BooksHERE IS A BOOK (SCOOP)

February 1940 -

Books

BooksTHE LITERARY ART OF EDWARD GIBBON.

June 1960 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksSHOW ME THE WAY TO GO HOME.

January 1960 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38 -

Books

BooksTHEATRE OF SOLITUDE: THE DRAMA OF ALFRED de MUSSET.

November 1974 By M.A.BILEZIKIAN -

Books

BooksTHE COLONIAL CRAFTSMAN

June 1950 By Virgil Poling -

Books

BooksTHE MISSISQUOI LOYALISTS

October 1938 By W. R. Waterman