A couple of years ago, a gent who pumps publicity for one of the Ivy League colleges was pondering the direction the race for the Ivy football title would take during that particular season. He had a three-part test that he applied to each team: offensive potential, defensive potential, and a final side of the triangle that he called something like "psychological intangibles."

That was back in 1973. Dartmouth had won the Ivy title during the four preceding seasons. It figured to be somebody else's turn. The odds of another title were about as long as flipping a coin and having it stand on edge. It wasn't a matter of percentages that our friend was contending with, but rather a basic assessment of the three pieces of his casually devised football barometer.

He considered the first two factors, and your favorite team was somewhere in the middle of the pack. Then he punched in Factor Three and" suddenly he was the voice in the wilderness, a non-Dartmouth man of all things, who figured that the special "intangible something" - call it "knowing how to win better than anyone else" - made Dartmouth his choice.

Then our man began to question his system as the Greenies lost their first three games. You know what happened after that. Six wins and a fifth, straight title. The guy came up smelling sweeter than Jimmy the Greek.

Factor Three went into hiding for Dartmouth in 1974 and for all the sweat, pain, and hope there wasn't much of Factor One either. Factor Two, the defense, held up pretty well and continues to look more than reliable. So what about One and Three this time around?

If you consider what everyone, including the aforementioned in-league sharpie, has said about this autumn's Ivy football ritual, it will be at least another year until Dartmouth regains its grip on the top rung. The reasoning is sound but the published judgments were made during the spring, long before it came time to put things on the line. Therein, perchance, lies the flaw.

For all of the leadership and inspiration that team captains can offer, most football teams develop a personality that is shaped by the quarterback. He is the drummer. Rarely can the position be shared. The last times Bob Blackman (in 1968) and Jake Crouthamel (last fall) tried to split the duties between two men, the result was a losing record.

When Crouthamel greeted his current team in September, the quarterback position prompted split vision because two men were presumed to be heading down parallel paths in quest of the starting job. Mike Brait is the senior who bears the asset of varsity experience, while Kevin Case, a junior, is the possessor of better size and raw ability. But it quickly became apparent that it wasn't going to be a drawn out affair. After two years of assorted frustrations, Mike Brait has finally arrived.

For two seasons, Brait worked behind Tom Snickenberger. There were times when he appeared at the brink of taking the starting job away from Snick, but it never came to pass. His height, only 5-11, prompted some to say he is too short to be effective. He disagrees despite an episode early in his freshman season when he cockily advised his coaches that he could throw drop-back passes against anybody. Crouthamel had Tom Tarazevits, a 6-6 All-Ivy tackle, stand with arms raised against a wall. The coach climbed up, marked the peak of Tarazevits' fingertips, and asked Brait if he could throw against an on-rushing defender of such dimension. The reply was obvious.

Fate dealt Brait a stacked deck as a sophomore. Dartmouth had lost its first three games and Crouthamel had made up his mind to give the starting nod to Brait. Two days before the next game, Brait broke his thumb in a fluke mishap (he was throwing a pass and his hand struck a lineman's helmet on the follow-through). He didn't see duty again until the season was virtually over.

Another hand injury early last season put him in the back seat again. He played a lot but never started. He and Snick had the added liability of operating with an inconsistent running game, and when Tom Fleming was injured the deep pass threat was negated.

For Brait, however, all of this is ancient history. From the outset this fall, he has taken command of the offense. He hasn't been perfect by any stretch, but he has given the offense a feeling of consistency that was lacking a year ago. The lad from Chicago never has lacked for confidence nor has he been alone in learning lessons from the frustrations of 1974.

While the tight end position has been unsettled, the opposite flank is occupied by two of the league's finest receivers. In Fleming and junior Harry Wilson, Brait has a pair of targets with excellent speed and grip. Across the line there is experience - Tom Parnon, Jud Porter, Lennie Nichols, Pat Sullivan, Mike Fitzgerald, and Phil Ward are the guards and tackles who flank a solid center, Jim Lucas.

If there was uncertainty among these players last year, today there is confidence. "We've learned so much," said Brait. "We know each other better and we believe in what we can do. The line feels it can move people for the running game and give us time for the pass game. We've made some adjustments in some of our pass routes and they seem more effective."

While Parnon and linebacker Reggie Williams are the titular leaders of this team and Brait seems to be adding his bit to the command structure, there is another segment of the "psychological intangible" that may be the most vital link of all: collective senior leadership. "Tom and Reggie are the co-captains but we have a totally strong group of seniors," said John Reidy, a regular in the defensive secondary. In numbers, it ranks with the seniors who led championship teams in 1970 and 1972. Whether the overall talent measures with the depth of those two groups remains to be seen.

"Leadership comes from many directions," said Brait. "It comes in different ways, from different people. It's something that we really didn't have within the team last year. It makes an awful lot of difference."

There's been a tendency, too, during practice to throw the ball more frequently, an opening of the Dartmouth attack which has been guided in past years by a philosophy of "Establish the ground game and it will make the pass game work." For Brait, who has long been itching to throw the ball, it seems like a bit of a dream. The ground game remains an improving but questionable facet. Last year, with Fleming hurting and the deep threat negated, defenses keyed on pressuring the running attack. A comparable approach this fall could have an unsettling impact on the opposition during the remaining weeks of the quest for the Ivy trophy.

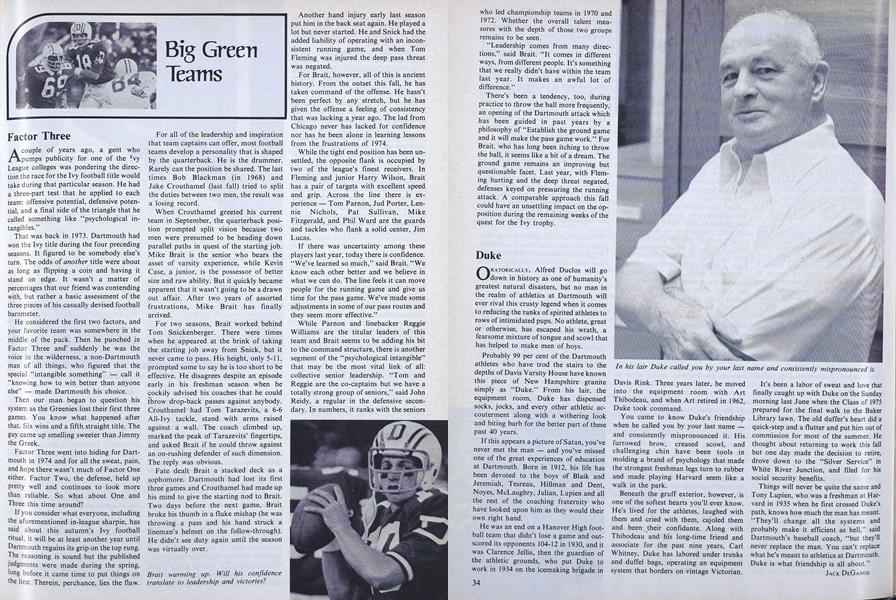

Brait warming up. Will his confidencetranslate to leadership and victories?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBefore the Revolution

October 1975 By ALBERT F. MONCURE JR., RONALD V. NEALE -

Feature

FeatureA Dialogue for Autumn

October 1975 By COREY FORD -

Feature

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe College

October 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Trolley Never Stopped Here

October 1975 By GEORGE W. HILTON

Article

-

Article

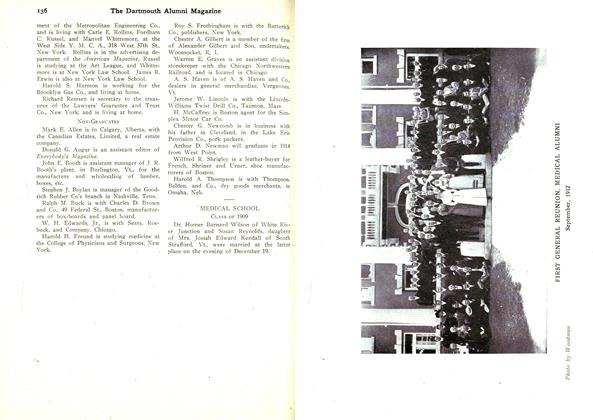

ArticleFIRST GENERAL REUNION, MEDICAL ALUMNI September, 1912

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

November 1918 -

Article

ArticleFIVE RECITALS REMAIN ON MUSIC PROGRAM

March, 1923 -

Article

ArticleGifts from the Old Guard

April 1941 -

Article

ArticleAlumni in Westchester Establish Scholarship

January 1954 -

Article

ArticleIn Memoriam: Cudworth Flint

MAY 1971 By THOMAS VANCE