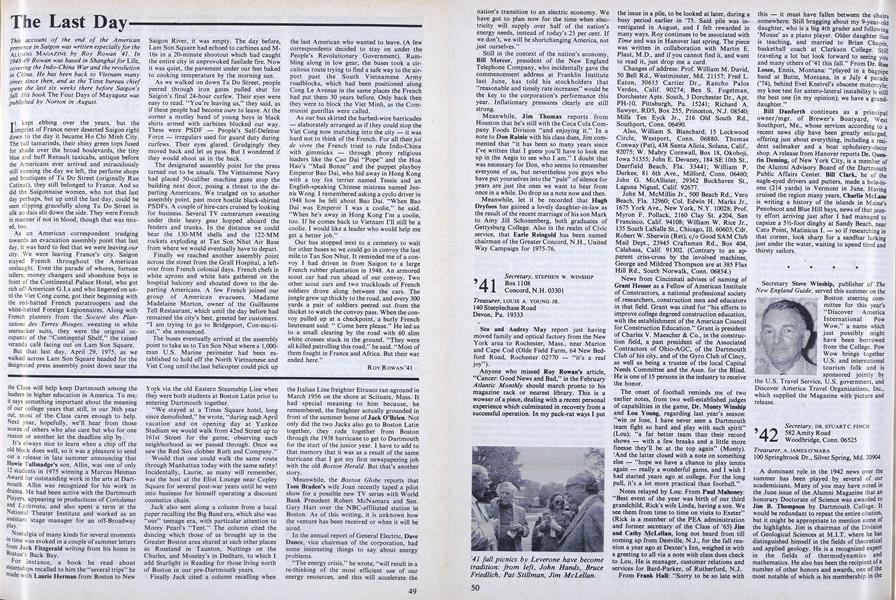

This account of the end of the Americanpresence in Saigon was written especially for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE by Roy Rowan '41. In1948-49 Rowan was based in Shanghai for Life, covering the Indo-China War and the revolutionin China. He has been back to Vietnam manytimes since then, and as the Time bureau chiefspent the last six weeks there before Saigon'sfall. His book The Four Days of Mayaguez waspublished by Norton in August.

It kept ebbing over the years, but the imprint of France never deserted Saigon right down to the day it became Ho Chi Minh City. The tall tamarinds, their shiny green tops fused for shade over the broad boulevards, the tiny blue and buff Renault taxicabs, antique before the Americans ever arrived and miraculously still running the day we left, the perfume shops and boutiques of Tu Do Street (originally Rue Catinat), they still belonged to France. And so did the Saigonnaise women, who not that last day perhaps, but up until the last day, could be seen slipping gracefully along Tu Do Street in silk ao dais slit down the side. They were French in manner if not in blood, though that was mixed, too.

As an American correspondent trudging towards an evacuation assembly point that last day, it was hard to feel that we were leaving our city. We were leaving France's city. Saigon stayed French throughout the American onslaught. Even the parade of whores, fortune tellers, money changers and shoeshine boys in front of the Continental Palace Hotel, who got rich off American G.I.s and who lingered on until the Viet Cong came, got their beginning with the red-hatted French paratroopers and the white-hatted Foreign Legionnaires. Along with French planters from the Societe des Plantations des Terres Rouges, sweating in white seersucker suits, they were the original occupants of the "Continental Shelf," the raised veranda cafe facing out on Lam Son Square.

But that last day, April 29, 1975, as we walked across Lam Son Square headed for the designated press assembly point down near the Saigon River, it was empty. The day before, Lam Son Square had echoed to carbines and M-16s in a 20-minute shootout which had caught the entire city in unprovoked fusilade fire. Now it was quiet, the pavement under our feet baked to cooking temperature by the morning sun.

As we walked on down Tu Do Street, people peered through iron gates pulled shut for Saigon's final 24-hour curfew. Their eyes were easy to read. "You're leaving us," they said, as if these people had become ours to leave. At the corner a motley band of young boys in black shirts armed with carbines blocked our way. These were PSDF - People's Self-Defense Force - irregulars used for guard duty during curfews. Their eyes glared. Grudgingly they moved back and let us pass. But I wondered if they would shoot us in the back.

The designated assembly point for the press turned out to be unsafe. The Vietnamese Navy had placed 50-caliber machine guns atop the building next door, posing a threat to the departing Americans. We trudged on to another assembly point, past more hostile black-shirted PSDFs. A couple of hire-cars cruised by looking for business. Several TV cameramen sweating under their heavy gear hopped aboard the fenders and trunks. In the distance we could hear the 130-MM shells and the 122-MM rockets exploding at Tan Son Nhut Air Base from where we would eventually have to depart.

Finally we reached another assembly point across the street from the Grail Hospital, a leftover from French colonial days. French chefs in white aprons and white hats gathered on the hospital balcony and shouted down to the departing Americans. A few French joined our group of American evacuees. Madame Madelaine Morton, owner of the Guillaume Tell Restaurant, which until the day before had remained the city's best, greeted her customers. "I am trying to go to Bridgeport, Con-nec-ticut," she announced.

The buses eventually arrived at the assembly point to take us to Tan Son Nhut where a 1,000-man U.S. Marine perimeter had been established to hold off the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong until the last helicopter could pick up the last American who wanted to leave. (A few correspondents decided to stay on under the People's Revolutionary Government). Rumbling along in low gear, the buses took a circuitous route trying to find a safe way to the airport past the South Vietnamese Army roadblocks, which had been positioned along Cong Le Avenue in the same places the French had put them 30 years before. Only back then they were to block the Viet Minh, as the Communist guerillas were called.

As our bus skirted the barbed-wire barricades - elaborately arranged as if they could stop the Viet Cong now marching into the city - it was hard not to think of the French. For all their joide vivre the French tried to rule Indo-China with gimmicks - through phony religious leaders like the Cao Dai "Pope" and the Hoa Hao's "Mad Bonze" and the puppet playboy Emperor Bao Dai, who hid away in Hong Kong with a toy fox terrier named Tessie and an English-speaking Chinese mistress named Jennis Wong. I remembered asking a cyclo driver in 1948 how he felt about Bao Dai. "When Bao Dai was Emperor I was a coolie," he said. "When he's away in Hong Kong I'm a coolie, too. If he comes back to Vietnam I'll still be a coolie. I would like a leader who would help me get a better job."

Our bus stopped next to a cemetery to wait for other buses so we could go in convoy the last mile to Tan Son Nhut. It reminded me of a convoy I had driven in from Saigon to a large French rubber plantation in 1948. An armored scout car had run ahead of our convoy. Two other scout cars and two truckloads of French soldiers drove along between the cars. The jungle grew up thickly to the road, and every 300 yards a pair of soldiers peered out from the thicket to watch the convoy pass. When the convoy pulled up at a checkpoint, a burly French lieutenant said: " Come here please." He led us to a small clearing by the road with 60 slim white crosses stuck in the ground. "They were all killed patrolling this road," he said. "Most of them fought in France and Africa. But their war ended here."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBefore the Revolution

October 1975 By ALBERT F. MONCURE JR., RONALD V. NEALE -

Feature

FeatureA Dialogue for Autumn

October 1975 By COREY FORD -

Feature

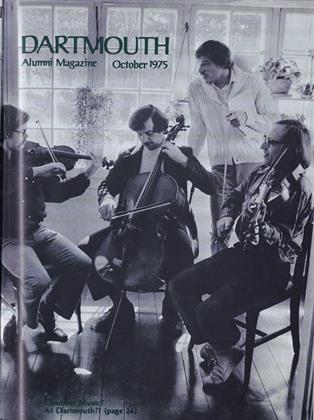

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe College

October 1975 -

Article

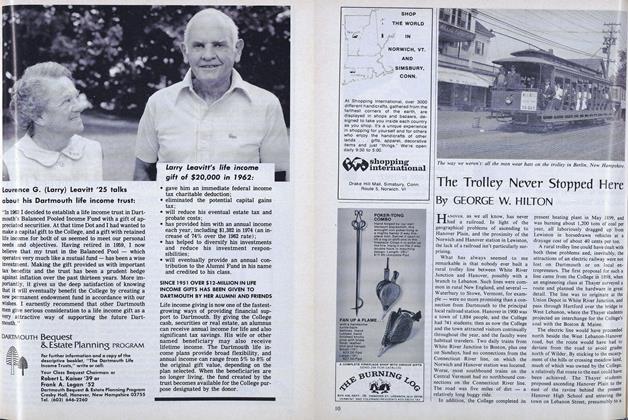

ArticleThe Trolley Never Stopped Here

October 1975 By GEORGE W. HILTON