Dealing with Dartmouth and the World in terms of alumni activity involves making choices every bit as difficult as those which went into showing how active the faculties of the College are. More than a thousand alumni are living abroad; a strong contingent work in the State Department and international agencies of all kinds; it would be almost impossible to sort out the number whose business activities include daily contact with other countries. Take a ferry across Hong Kong harbor and, at a few removes, you are in the hands of Edmond T-C. Lau '61 TU '62; go to see a movie at the National Film Theatre in London and it will have been chosen by Ken Wlaschin '56; listen to the CBS chief correspondent in Paris and you're getting your facts from Tom Fenton '52 the list could go on and on to the point of tedium. The four profiles which follow, however, are meant to reflect the diversity of achievement of four people, one from each decade through which John Dickey's presidency extended, who have done exceptionally well the work they have chosen to do. And then there are two essays about men who came to Dartmouth from abroad and now work for the cause of international understanding in quite different parts of the world; again they are but representative of many.

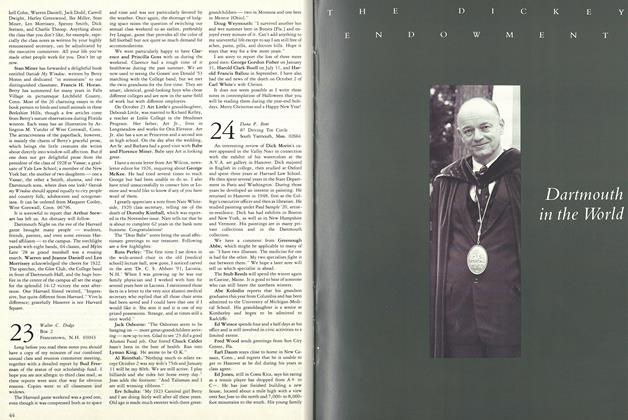

Ronald I. Spiers '48,

United States Ambassador to Pakistan

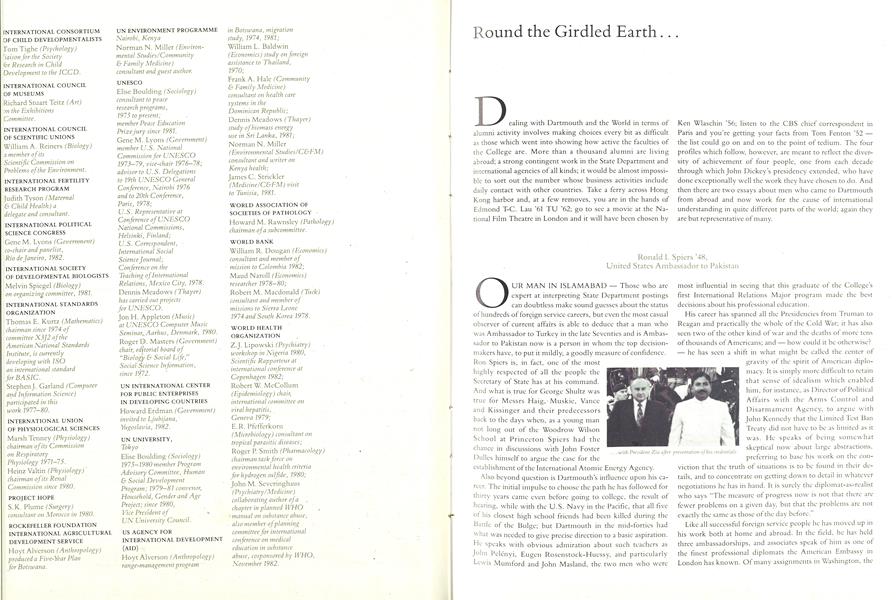

OUR MAN IN ISLAMABAD Those who arc expert at interpreting State Department postings can doubtless make sound guesses about the status of hundreds of foreign service careers, but even the most casual observer of current affairs is able to deduce that a man who was Ambassador to Turkey in the late Seventies and is Ambassador to Pakistan now is a person in whom the top decisionmakers have, to put it mildly, a goodly measure of confidence. Ron Spiers is, in fact, one of the most highly respected of all the people the Secretary of State has at his command. And what is true for George Shultz was true tor Messrs Haig, Muskie, Vance and Kissinger and their predecessors back to the days when, as a young man not long out of the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton Spiers had the chance in discussions with John Foster Dulles himself to argue the case for the establishment of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Also beyond question is Dartmouth's influence upon his career. The initial impulse to choose the path he has followed for thirty years came even before going to college, the result of hearing, while with the U.S. Navy in the Pacific, that all five of his closest high school friends had been killed during the Battle of the Bulge; but Dartmouth in the mid-forties had what was needed to give precise direction to a basic aspiration. He speaks with obvious admiration about such teachers as John Pelenyi, Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, and particularly Lewis Mumford and John Masland, the two men who were most influential in seeing that this graduate of the College's first International Relations Major program made the best decisions about his professional education.

His career has spanned all the Presidencies from Truman to Reagan and practically the whole of the Cold War; it has also seen two of the other kind of war and the deaths of more tens of thousands of Americans; and how could it be otherwise? he has seen a shift in what might be called the center of gravity of the spirit of American diplomacy. It is simply more difficult to retain that sense of idealism which enabled him, for instance, as Director of Political Affairs with the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, to argue with John Kennedy that the Limited Test Ban Treaty did not have to be as limited as it was. He speaks of being somewhat skeptical now about large abstractions, preferring to base his work on the conviction that the truth of situations is to be found in their details, and to concentrate on getting down to detail in whatever negotiations he has in hand. It is surely the diplomat-as-realist who says "The measure of progress now is not that there are fewer problems on a given day, but that the problems are not exactly the same as those of the day before.' Like all successful foreign service people he has moved up in his work both at home and abroad. In the field, he has held three ambassadorships, and associates speak of him as one of the finest professional diplomats the American Embassy in London has known. Of many assignments in Washington, the two most recent were at the assistant secretary level, in key areas of the State Department, first as Director of the Bureau of Politico-Military Affairs, and then, before going to Islamabad, as Director of Intelligence and Research.

The conversation turns to the matter of ambassadorial life styles, and one detects a certain amount of nostalgia for the years when, like the Urdu-speaking junior officers on his current staff, he could spend time getting to know at first hand something about the day-to-day ordinary goings on in the country he was working in. But an American ambassador in the 1980s must have a constant bodyguard assigned to him, and drive in an armored car; and an ambassador at any time inevitably has a range of contacts which is limited to the very senior people in government and society. So one is made aware of the sadness over what is lost as well as the satisfaction over what is gained which come with moves up the foreign service ladder.

Those expert State-Department-watchers see him as one of a very small handful of people who are in line for the terribly demanding job at the top of his profession the chance to serve as Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs. Whether that opportunity comes his way or whether what he has ahead of him are more years in United States embassies in critically important capital cities, he will bring an unusually rich set of experiences to the task, as well as a palpably strong sense of commitment, as well as a growing-by-the-year resolve to try to get in an annual visit to his Vermont family homestead for the best kind of R and R he knows.

Christopher S. Wren '57.

New York Times Bureau Chief in Beijing

A FAIRLY HUMDRUM EXISTENCE "Have lived in four foreign countries and worked or traveled in about forty others. Otherwise, a fairly humdrum existence over the past twenty-five years. Two of the three sentences in Chris Wren's entry in the '57 25-Year Book, and they suggest that among all the qualities which have made him an outstanding journalist is a certain wry sense of humor.

Here is a man who, in 1963, could check in a rental car which has just been wrecked by people who resented the arrival of New York reporters lopking for news in Bogalusa, Louisiana, a car with a Coke bottle still embedded in what was left of its windshield, and say in response to the clerk's routine "How do you like the car?" "I like it a lot, but I'm not sure how much you're going to." A man who immediately after filing the story about being, in effect, run out of town, left his office at LOOK magazine and went to the deep south for two years to write about what he considered the most important issue of the era. Here is a man who must have run a risk or two to get the material for the reporting which won him his first Overseas Press Club citation the 1969 story of how the Greek generals were dealing with politicians of whom they did not approve. (He has since received other O.P.C. awards: in 1970 for his dispatches from Vietnam, and in 1974 for his reports for the New York Times about the first American expedition to climb the Pamir range of mountains in Soviet Central Asia.) Here is the man to whom the Times has entrusted the post of Bureau Chief in, successively, Moscow, Cairo and Beijing.

He has always been on the move. His parents were in the theatre business when theatre business could mean a lot of travelling, and if he and his twin sister were not literally "born backstage" they came very close to it. There seems to be every reason to assume that his four years at Dartmouth will prove to be, by the end of his working life, the longest uninterrupted stay in one place he has known; and he certainly acknowledges that the three or four square miles surrounding Ledyard Bridge come closest to being his "roots" place. A telephone conversation brings out the fact that the College gave him much more than a solid chunk of time in one location, for he makes clear that he found its isolation the ideal context in which to sort out what it would mean to do something interesting with his life; and its spirit encouraged him to believe in the idea of the road less traveled by.

His closest friend, the man with whom he wrote Quotations from Chairman LBJ and The Almanac of Poor RichardNixon, as well as a picaresque novel about the youth culture of the Sixties, speaks of his having the perfect temperament for a journalist, "He gets up every morning wanting to know what's new. And he always knows that there's something more to find out." The conversation reminds one that Chris Wren was a very successful child actor, is an accomplished musician who has had some of his songs recorded by Johnny Cash (whose biography he subsequently wrote), and is a mountaineer in the international class. But after a lot of heady reminiscing comes the sobering thought called for by the request that he speculate about what might lie ahead in the career of one who has accomplished so much. "I guess he would do fabulously well for the Times in London or Paris, but I can t help wondering what the effect would be if someone who is one of the few people to have worked close to the center of things in both Moscow and Beijing" (the triend knows that Wren learned Russian at Cambridge and Chinese at Stanford) could bring his intelligence and his honesty to bear upon the State Department or the Pentagon."

Such a man, one who can end one of his reports by quoting a Russian climber's "Mountains separate nations. They do not separate mountaineers," surely has much to offer his country and the world. He was, after all, born on February 22nd.

Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. '63,

Vice Chairman of the American Express Company

DON'T LEAVE HOME WITHOUT. . . Lou Gerstner has on display in his office at American Express some words from John le Carre, "A desk is a dangerous place from which to view the world." They have special significance when you are the man in charge of that world's most extensive network of services devoted to travellers.

Extensive is surely the word: the company does business in 130 countries and deals with credit card membership accounts in 20 different currencies. Indeed one of the most important facts to take in about American Express is that it doesn't just look after Americans but rather helps travellers of all nationalities travelling in virtually all the nations on the planet. There is a huge matrix of activity affected by what its executives decide, and when it comes to the travelrelated side of the enterprise (which is what most people think of when they see that powder blue sign), Gerstner leads the band.

Just how huge the matrix is may be seen from the statistics which show that travel and tourism constitute the secondlargest world industry (only the petroleum business is bigger) in terms of the volume of money changing hands. In a host of countries the travel and tourism turnover comes either first or second or third in the components which make up the gross national product; and especially in countries whose history or natural beauty make them unusually attractive to tourists, the money brought in by them is often the primary source of foreign exchange, even, in a couple of instances, for oil-exporting nations.

It is an industry which is growing all the time and which has the virtues of providing a lot of work for a lot of people in a lot of places, as well as being what one might call non-pollutant. Above all it has a major, contribution to make to international relations: no matter how cautious and rhetoric-avoiding it may be, any statement about travel among nations will surely suggest that it helps to break down barriers and promote goodwill. And an electorate informed by first-hand experience about the lives led by people of other lands is likely to make better choices than one that is not.

People who work with Gerstner speak of him as a thoughtful and "aware" man; and one quickly senses that his being in a service-oriented (rather than product-dominated) business is a matter of choice rather than accident. When he speaks of his current fascination with China it is principally in terms of the attractiveness of the people. When he talks about the American Express worldwide staff he recalls instances in which their service award has gone to men and women who have gone extraordinary distances beyond the call of duty. And he heeds the warning implicit in le Carre's aphorism by travelling frequently and all over the world, to see for himself how policies which he a,nd his colleagues established are being implemented for the benefit of the travelling public. Always time is too short to explore a new scene as thoroughly as he would wish.

Dartmouth cannot be said to have set his course precisely towards his current preoccupations, but it certainly broadened his horizons, and gave him his first opportunities to meet and make friendships with foreigners. Like many others of his generation, though, he feels a little shortchanged when he thinks of how the intensive study of foreign languages and the extensive foreign study program came after his time. For all that, he is now responsible for one of the most far-reaching foreign study programs anyone has ever engaged in, and he is clearly taking it very seriously indeed.

He likes the fact that you don't have to read very far in American fiction before coming across a reference to a rendezvous set for an American Express office in some foreign city. His is, in fact, a company which likes to think of itself as something of an institution, providing a modicum of extra security for millions of travellers every year. Lou Gerstner has another context in which to set a watch lest the old traditions fail.

Kimberley Ann Conroy '76,

Institute of Current World Affairs Fellow Mexico City

THE ROAD TO SAN JUAN BOSCO, AND BEYOND "For National Public Radio this is Kim Conroy in San Salvador." No one who had come to know her in the years since she arrived at Dartmouth would have been surprised when they heard her on All Things Considered" reporting on the El Salvador crisis during the Duarte era, even if they had no idea that she was anywhere near that country then. In fact it is probably fair to say that just about the only thing that could surprise them would be the news that she had settled down in Connecticut or some such place; even New York City would not seem right unless the "settling down" had something to do with working in the front line of one of that city's big problems.

Right now she is in another huge metropolis Mexico City with huge problems, and the letters she has been sending back to the Hanover headquarters of the Institute of Current World Affairs (the sponsors of this latest of numerous assignments in Central America) reveal once again her determination and. her perspicacity in seeing into the nature of difficulty.

In any report about this extraordinary young career pride of place is bound to go to the project in San Juan Bosco, for it is singularly original and admirable. Under the aegis of a Reynolds Scholarship (Hats off to a selection committee with the breadth of vision to respond to what must have been one of the most unusual submissions in the history of the program.) Kim Conroy was able to demonstrate that vision, hard work and sheer audacity can turn.life around.

The Reynolds year went to implementing a study made for the Save the Children Federation immediately after she graduated with the very special Class of '76, a study of the feasibility *of establishing a cooperative in a village in Honduras. The idea was that such a cooperative would deal with the waste of a valuable natural resource at the same time as bringing some kind of hope to a desperately impoverished community. Up to 1976 San Juan Bosco had had an abundance of mangoes but no idea about what to do with the! fruit except to sell it for immediate consumption at harvest.time and let whatever was not bought spoil and rot away. For'the last five years, however, it has had a fruit canning cooperative which, against all the odds, successfully produces and markets mango puree (based on a formula worked out by the ingenious Conroy), mango jam and mango candies, an enterprise which brings the eighteen member families of the cooperative a better living.

The full story of her work leading a group of women every one of whom was older than she was, through every stage of planning, construction, organisation and starting up the cannery (and then writing a manual to guide others interested in doing similar things) needs a monograph rather than a couple of paragraphs in a profile; but the essential beauty of it can be seen even in the merest outline. And it made possible and almost inevitable an involvement with Latin America (the study of which had been the focus of the special major she had devised for herself at the College) which has become total.

After the Reynolds work came a two-year stint as a consultant for the Mexican government's Integrated Rural Development Program, followed by a year as advisor to its director during which she had responsibility for some negotiating with agencies such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank as well as for coordinating a pilot productive projects program for peasant women in four of Mexico's states. The I.C.W. A. fellowship which followed that work has given her the opportunity to travel widely and her reports from Honduras, Brazil, El Salvador and Guatemala as well as from Mexico make it clear that if, as seems likely, her future is as journalist she will have as much success there as she has had as an organizer and activist on behalf of others. After the Fellowship she will head for Rio de Janeiro where her Portuguese will doubtless quickly become as fluent as her Spanish, and where her indomitable spirit and keen eye for the key details of the situations she has to deal with will surely lead to some adventures which may turn life around for some more people who know nothing whatever about Miss Porter s School or even Dartmouth College, but who owe much to one of their more extraordinary young alumnae.

Yoshihiro Nakamura '68,

Director of the Inspection Division, Foreign Ministry of japan

"AFTER ALL, WE NEED EACH OTHER VERY MUCH." After all the peace treaties were signed and Japan joined the United Nations, the man entrusted with the heavy responsibility of being his country's first ambassador there was a Japanese diplomat who had been an undergraduate at a small New England college. One cannot avoid the thought that some small part of Japan's success in coming back into the family of nations came from the four years at Amherst which helped to shape one man's life. The inter-relatiojiship comes easily to mind when one takes in the career, a generation later, of Yoshihiro Nakamura. In the fourteen years since he graduated from Dartmouth, majoring in economics, Nakamura has engaged in an extraordinary series of duties for his country. In his first posting, to Australia, he soon found himself heavily involved with economic negotiations in a country for which Japan ranks in importance after only the United States and Great Britain, in terms of its economy. A period followed as the official in charge of atomic energy matters in the Scientific Affairs division of the Japanese Foreign Ministry, years during which agreements were made with several countries and the existing one with the U.S. was revised. Then came a stint of working sixteen-hour days as the officer in charge of oil negotiation activity within the Ministry during the period of the Arab Oil Embargo, days which brought several dozen journeys to European and Middle Eastern capitals (and the realization that perhaps his physical fitness was in some measure "owing to my Dartmouth days.")

In 1977 came a two-year assignment which is the only one about which he writes in any terms other than exhilaration and satisfaction two years of frustration as the third-ranking member of the japanese delegation to the Conference of the Committee on Disarmament in Geneva. Because nothing could happen unless the two superpowers reached agreement, the CCD was eventually "not a place of negotiation but of deliberation" and so much speech-writing, report-preparing and interviewconducting without any sign of progress, "such a static job," led to the urgent request for a transfer to an embassy posting. At least nothing was static then, for he was made counsellor of the Japanese embassy in Baghdad (and Charge d'Affaires during a seven-month absence by the ambassador) not long before the start of the Iran-Iraq war, and there followed more long and exhausting days dealing with the crises within the sizeable Japanese population in the country.

Then a year as Deputy Director of the Overseas Public Relations Division at the height of the U.S. anxiety over the trade surplus, and now the task of making sure that all his country's embassies and consulates and permanent missions are functioning as they should. It is small wonder that the invigorating experience of working hard at Dartmouth, and the memories of a band of teachers to whom he feels especially close, often come back to mind, or that the U.S.-Japan relationship is so important to him.

A high priority is expressed in a sentence from a letter to Hanover: "We must find a better formula for cooperating with each other, and not spend a lot of energy in blaming a partner. After all, we need each other very much."

Saihou Saidy '74,

Desk Officer, United Nations High Commission for Refugees, Ethiopia

"A BLE TO DO A LITTLE SOMETHING'- Never underestimate the power of a Dartmouth T-shirt. If Jonathan Young '64 had not worn his from time to time while he was working in the Gambia for Operation Crossroads Africa, Saihou Saidy's contribution to Dartmouth's internationality might never have been possible, for it was the recollection of this identifying garment worn by a person who had impressed him greatly that brought tocus to his aspiration to seek a university education in America.

Even before he made the long journey from West Africa to New England, Saidy knew he wanted to work in international affairs, and with the help of teachers like David Baldwin, Donald McNemar and Leo Spitzer, he was able to put together a Government major enriched by the incorporation of as many internationally-oriented courses as could be fitted in. With a Dartmouth graduate fellowship he went to the Johns Hopkins School for Advanced International Studies, and after graduation returned to the Gambia to begin a career with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; but he was soon overtaken by a sense of frustration, stemming from too many changes of assignment too fast, and too strong a feeling that he was not accomplishing much. A period as a Washington-based consultant led to the opening of a door into the kind of work he had always had in mind doing something useful where the need was great and he has been in East Africa ever since, working for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees.

People with Saidy's training and abilities have special value as desk officers, people who are good at sifting, interpreting, organizing reports from the field so that they tell a cogent story to the decision-makers in Geneva, and there seems to be no doubt that he does that kind of work very well. Indeed his current assignment in Ethiopia has clearly taken him into a responsible post in a highly complex situation, where those refugees who were victims of circumstance, innocent people fleeing from the crossfire of civil war, arc being helped to return to their homeland from camps spread among three neighboring countries, and assisted in their efforts to begin life again.

Desk work may be important, and he may do it well, but the signs of satisfaction are most vivid when Saidy shares his thoughts about his spell as a field officer at Juba in the Sudan. There the Commission had sent him to deal with the day-to-day problems of Ugandan refugees in Sudanese camps, and the posting brought him the opportunity for the sort of pragmatic decision-making that brings results that can be seen right away. It also brought him a new Dartmouth friendship, with Whitney Foster '64 who, as representative ot the United Nations Development Program, made many things possible. There, in the heart of the ordeal of refugee life, Saihou Saidy found that every week brought a new mission, and every day the knowledge that he "had been able to do a little something" to relieve misery and restore hope. It was, he says, very very rewarding.

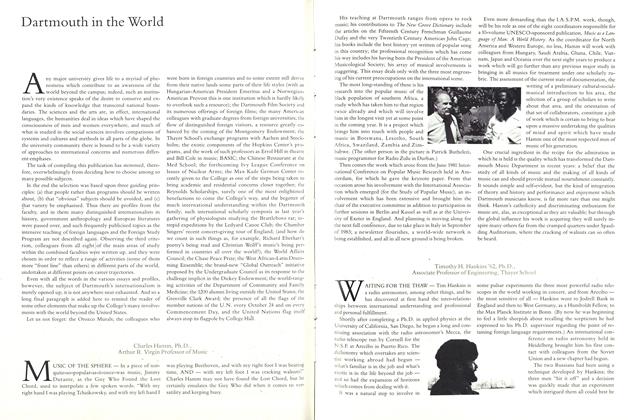

with President Zia after presentation of his credentials

planting a tree in Beijing

. . . being presented to the Queen of Thailand

...interviewing President Duarte (r.)

...(c.) with Garcia Robles at Geneva disarmament talks

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

December 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhere They Hang Their Hats

December 1982 By Steve Farnsworth and Jean Korelitz -

Feature

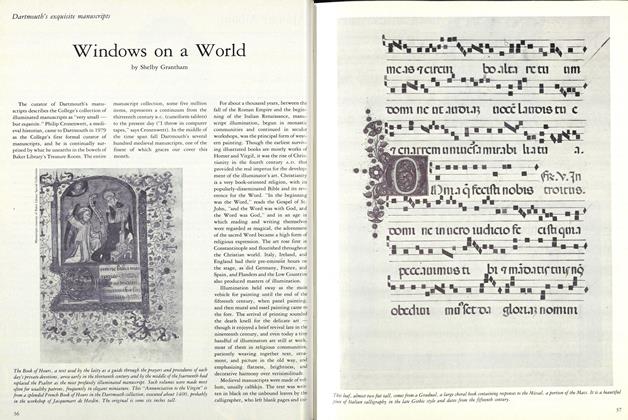

FeatureWindows on a World

December 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the World

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleTHE DICKEY ENDOWMENT

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleOff to a Good Start.

December 1982 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47