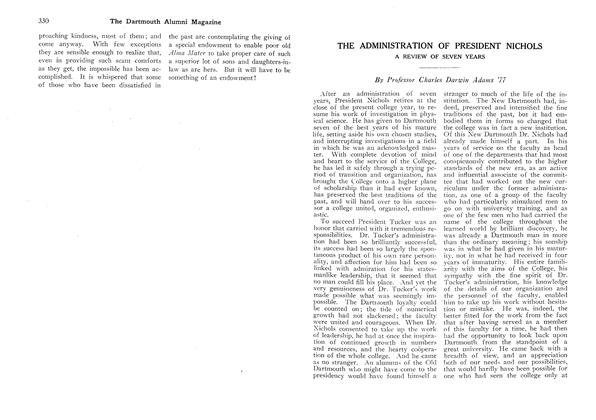

EVERETT W. WOOD '38 is a resident of Hanover. True, a traveling man, he's out of town a lot, but "I'm at home there, whether I'm there or not."

A senior pilot with Pan American World Airways, Wood will have logged more than 30 years' service and 29,300 hours in the flying clippers when he retires from the cockpit in February. Though he's hung his hat for varying intervals in Paris, Berlin, Kabul, Hong Kong, and Saigon, each year since the war he's managed a pilgrimage "home," usually timed for a grouseshooting expedition to northern Vermont with old friends of Bait and Bullet days. For three years in the late '50s, assigned to the New York-Lisbon-Johannesburg run, he was "in residence" between trips as well.

Ev Wood has been hooked on flying since he joined the Navy as an aviation cadet in 1940. He was decorated with the British Distinguished Flying Cross for sinking a German U-boat on patrol off Iceland, one of a handful of Americans so honored, and earned the Air Medal for 70 missions. Discharged in 1945 as a Lieutenant Commander, within months he signed on as a pilot with American Overseas Airlines, which was absorbed five years later by Pan Am.

An incorrigible volunteer, Wood has accumulated a remarkable record of extraordinary assignments above and beyond the normal unroutinized routine of the commercial flyer. In 1948 and '49, he was flying the hazardous corridor of the Berlin Airlift, ferrying food and coal into the city. From 1961 to 1965, he was chief pilot, in cooperation with the U.S. AID program, of the fledgling Afghanistan airline, training native pilots, "flying pomegranates to India and Moslem pilgrims to Mecca," over towering mountain ranges and across "1,500 miles of moonscape" to the Mediterranean. From there, he returned to Germany as a check pilot for their air force. In 1966, it was training civilian Vietnamese crews for a new national airline, rigorous work with prop planes and pilots "large in spirit" but diminutive in size - the heftiest weighed in at 117 pounds - scarcely able to cope physically with the aircrafts' controls.

Based in San Francisco from 1967 to 1970 on Pan-Am's round-the-world route, he volunteered for side missions to Vietnam, ferrying American servicemen out for brief R & R in Taipei, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Bangkok. "In no sense do I support the moral and military morass which is Vietnam," he wrote at the time. "I keep bidding those trips out of sympathy with the first victims of the sorry mess out there - our troops who must slug it out."

Despite the confrontation with man-made trauma and the vagaries of weather, Wood regards flying in a sense as an escape - in the words of Lin Yutang - "from what the other people of the world are busy about." His is "a very privileged profession," he contends, its advantages more than compensating for the wars, the hi-jackers, and a certain inherent rootlessness. From time to time he's flirted in a desultory fashion with thoughts of earth-bound ventures, but his commitment to "our bird's-eye view of a lot of seascapes, landscapes, deserts, cities, and mankind in trouble" has never really wavered. The strongest lure of the wild blue, he says, is a relationship with colleagues - comradely, interdependent, trusting - unlike that of more humdrum occupations. Close behind is the undeniable glamor of easy access, on a week-to-week basis, to widely different people and their cultures. Although "the increasing demands of the cockpit" of modern airliners and the comparative isolation of vast new airports have diminished the pilot's opportunity to know the countries he visits, compared to what it was in the '60s - "the golden days of flying" - the charm of the weekly 24-hour layover in Prague or Bangkok remains.

The esprit de corps of Pan Am's pilots is illustrated, Wood notes, by the voluntary paycut they took last year to help the airline in its fight for survival against two severe handicaps: competition on international routes with subsidized foreign carriers and the interdict against Pan Am's flying domestic routes. Wood himself has lobbied in Washington for the Airlines Fair Practices Act sponsored by his New Hampshire Senator Norris Cotton, which provides for mutual landing fees and mail pay between countries and the promotion of travel on American lines, particularly for U.S. government personnel on business. He's confident that Pan Am will emerge "a smaller but stronger airline," thanks in good measure to its internal "awareness program."

Among the privileges of the man in the flying machine is the liberal time off, 12 to 14 days each month, which flight crews put to widely varied use. A literate cosmopolitan, thoroughly fluent in French and German with "bazaar Persian", to boot; outdoorsman; connoisseur of fine foods, fine wines, and great cities, Ev Wood has made his time count fishing the world's best streams, skiing its best slopes, reading and writing, and indulging a lively curiosity about people and places. "I have been sustained by great writing," he says, since undergraduate days as an English major. He admits modestly only to being "a pretty fair cook," but he's published articles in Gourmet magazine and plans in retirement to write more about his bird's-eye view.

After last month's grouse-shooting, Wood returned to Berlin, where he's been based for the last few years, flying Pan Am's European routes. Visibility is still limited on what comes after his final commercial landing, come February. But it seems likely that Baker Tower will loom clear on the horizon more frequently. The traveling man may find that "You Can Go Home Again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Delicate Balance

November 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureOBESITY

November 1975 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureFairly Faced

November 1975 By WILLIAM W. COOK -

Feature

FeatureSome Faults, Some Solid Achievements

November 1975 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

November 1975 By WALTER C. DODGE, THEODORE R. MINER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

November 1975 By RICHARD W. LIPPMAN, A. JAMES O'MARA