This fact-packed, meticulously documented history ranges from the first Indian-white encounters when the races were "on a plane of relative equality" to forced migrations westward and the loss of Indian land's to the whites to 1973 when "a carefully planned, artificially staged media event" at Wounded Knee "symbolized the emergence of a voice which celebrated separation instead of integration."

Washburn's tightly knit synthesis skilfully avoids generalizations about the Indian. With compassionate interdisciplinary study he reveals the awakened national consciousness about the Indian's status. Significantly, he abolishes the wooden Indian stereotype by discussing variations in "languages, customs, personalities, and beliefs." He decries "the ignorance of Indian culture, fatuous self-righteousness, and land hunger [which] combined to push the Indian reeling into the twentieth century without . . . the economic supports or cultural values that had previously given his life meaning."

The Indian's ecologically balanced perception of man's place in nature is discussed; and also the concept of property "dominated by comaunal rather than individual goals." His oralaural traditions are contrasted to the white's visual, static world view. These differences, Washburn believes, "resulted in continuing tragedy based on the inability of either side successfully to comprehend - let along accommodate - the view of the other."

The chapters on Indian Personality and The Reservation Indian emphasize the Indian's trust and "faithfulness to his pledged word;" his desire to avoid conflict when possible, and his offers of intermarriage with the whites, which in light of subsequent events Washburn thinks was a lost opportunity for both races.

There's bite in Washburn's comment: "Many observers considered the Indian in his untutored state to possess Christian values. Yet whites were unconsciously critical when they saw the Indians seemed to 'take no thought for the morrow' and lacked such civilized traits as selfishness."

Treaties with Indians were made and broken. They were forced to move to poorer lands and finally reservations because of the government's "political advantage, cultural blindness, and economic greed."

Washburn describes the devastating effects on Indians lacking immunity of the white man's communicable diseases. The aim of inferior educational systems, one missionary wrote, "was to teach the Indians to live like white people."

Washburn's conclusion: "Culture never has been ... a force to be overcome by [the] military, congressional legislation, or educational edicts."

The bitterest irony was granting most Indians "citizenship" in 1887. I recall that in 1924 my mother, a Yankton Sioux, received a 25-cent American flag pin signifying "citizenship" in her own land.

The image: a Susquehannock warrior, 1634,engraved in Frankfurt by Theodor de Bry.

THE INDIAN IN AMERICA. ByWilcomb E. Washburn '48. Harper& Row, 1975. 296 pp. $10.

A specialist in communications and linguistics,Professor Hardman (whose tribal name isTunkanwasten) is Dartmouth's seventhAmerican Indian graduate.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

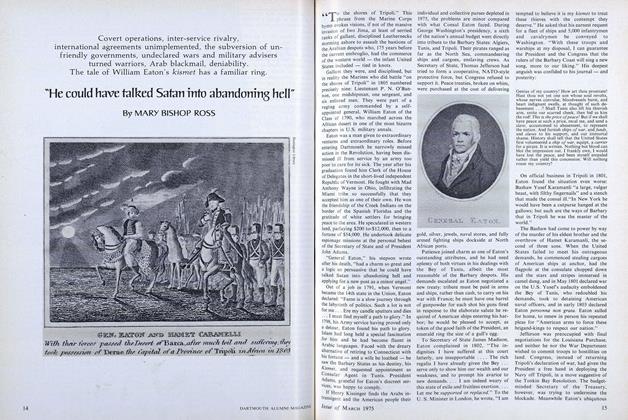

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

Feature"How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm?"

March 1975 By ROBERT L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

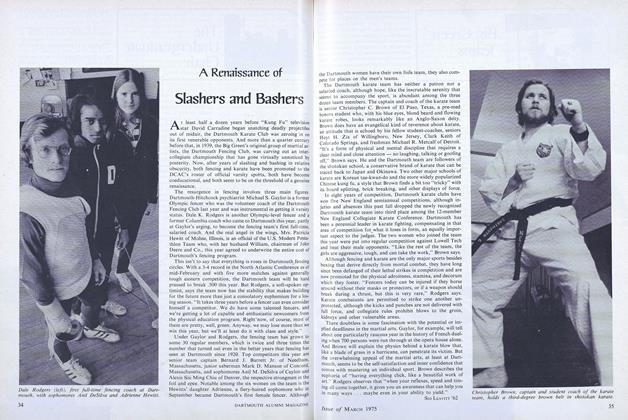

FeatureA Renaissance of Slashers and Bashers

March 1975 By SID LEAVITT '62 -

Article

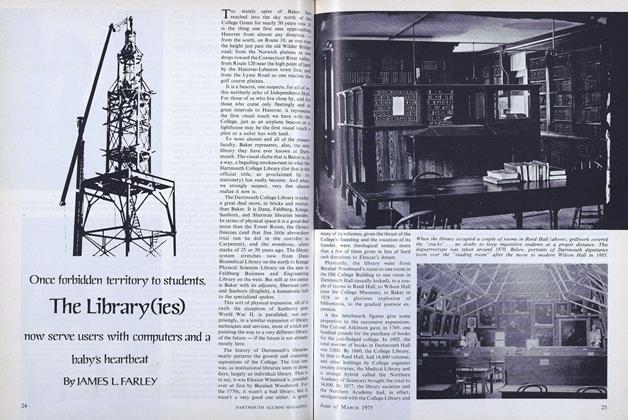

ArticleOnce forbidden territory to students, The Library(ies)

March 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE

BENEDICT E. HARDMAN '31

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE MAGNIFICENT PARTNERSHIP.

March 1955 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Books

BooksSTRATEGY AND COMMAND: THE FIRST TWO YEARS.

OCTOBER 1963 By ERNEST H. GUSTI '43 -

Books

BooksTHE HUMAN MIND

JUNE 1930 By G. W. Allport -

Books

BooksTHE FAIR RATE OF RETURN IN PUBLIC UTILITY REGULATION

October 1932 By James P. Richardson -

Books

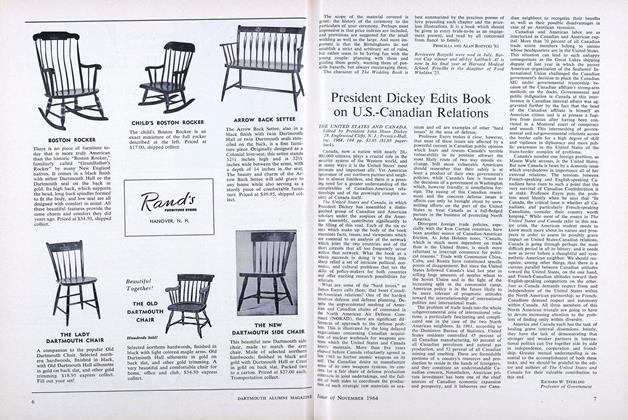

BooksTHE UNITED STATES AND CANADA.

NOVEMBER 1964 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Books

BooksTHINK ON THESE THINGS,

May 1942 By Roy B. Chamberlin