At a recent Dartmouth Horizons program I was asked what the three most important problems facing the College were. I replied, "One, we do not have enough money; two, we do not have enough money; three, we do not have enough money!"

Authors have referred to the 1960s as the golden age of higher education in the United States. The academic year 1969-70 is cited as the beginning of severe new problems, what Earl Cheit has called the "new depression in higher education." Seven of the eight Ivy presidents have taken office since that time. Each of us came with dreams of providing brilliant academic leadership for his institution, and each of us has had to spend a major portion of his time worrying about finances.

In the decade of the '6os the Dartmouth budget increased by 11.1 per cent a year. This was a time when inflation was at or below the three per cent level, and the student population increased only slightly. In the last five years, in spite of run-away inflation, a large increase in the undergraduate population, the M.D. program, and new construction, our budget has increased only 8.6 per cent per year. But Dartmouth, like her sister institutions, faces serious financial problems.

Many separate causes have contributed to this deterioration During the 19605, federal aid to higher education became a major factor in the financing of colleges and universities. Since that time there has been a sharp decline in such aid, particularly as measured in constant dollars. Dartmouth has been relatively for- tunate in that, except for the Medical School, it had not counted heavily on federal funds. But the decline has created a very serious problem for the Medical School, it has forced us to freeze the number and size of our Ph.D. programs, has made it much more difficult to finance them, and has led to a loss of outside support for faculty research.

Secondly, we have been hit with double-digit inflation. There is no way that we can quickly increase our sources of revenue. After two decades of making improvements in the economic status of all those who work for the College, we now find ourselves giving raises that do not even keep up with inflation. We have been forced to increase student charges faster than any of us would like, and yet other sources of income do not keep up with the escalation of expenses. The quadrupling of the cost of heavy oil added a new burden of about a million dollars a year to the College's budget, in spite of a concerted effort to save energy. And the Dow Jones plummeted from 1,000 to 600!

During the 19605, Dartmouth was a leader in developing more sophisticated investment strategies. The concept of "total return" freed the Trustee investment committee from a concern as to whether it generated considerable yield or invested in equities that had good prospects of appreciation. The task became the maximizing of total return. This investment strategy was coupled to a fairly complicated formula that made sure the amount spent from investments was prudent. A national study showed during this period that Dartmouth, under the guidance of John Meek, had one of the best investment records in the nation. The historical evidence seemed to show that the best long-range strategy was investment in high-growth, relatively low-yield equities. As a result, we and our sister institutions (and major foundations) were hard hit by the stock market of 1974. While the yield of these equities has remained very good, there has been a huge drop in market value and no usable appreciation.

The Board of Trustees is confident in the eventual recovery of the American economy. The problem is how to support the College in the interim. At a special meeting on March 1, 1974, the Trustees agreed to a five-year strategy of determining the maximum prudent spending rate from endowment based on a realistic forecast. Spending from true endowment funds will be limited to the previously established "total return formula," and the difference will be made up by drawing down the principal of quasi-endowment funds. These are funds for which the Trustees have no legal obligation to maintain the original principal; in effect they are reserves accumulated in more affluent times. Nevertheless, once such funds are drawn down, they no longer generate income for the College - a fact which makes us very careful to control the spending rate.

The Trustees have approved a carefully constructed formula to assure that we will "catch up" at the end of five years; indeed, if their forecast is correct, even the quasi-endowment funds will increase slightly during this period. For 1974-75 the Board set $8.9 million as the maximum reasonable amount to spend from endowment. They estimated that this could be increased by six per cent per year, subject to annual review. It is a sad comment on the performance of the stock market that at the first annual review the Trustees had to decrease this annual escalation to four per cent per year. This means that our endowment income becomes a lesser percentage of our total budget each year.

There has been one very important favorable development. The Alumni Fund has doubled within the past five years. Without this tremendously generous support on the part of the alumni our problems would not be manageable today.

For the first three years of my administration we had to slow down the rate of expense growth. In the last two years we have had to go beyond that and make significant cuts in our activities. My goal throughout this period has been to eliminate all "fat" in the budget, and then to cut those activities that have the least direct impact on the quality of education. I am convinced that no matter what sacrifices we have to make, the one thing we can not afford to do is to compromise quality. Institutions that have made such compromises have started a downward spiral from which they may never recover. Unless Dartmouth offers a clearly superior education, why would students want to come to Dartmouth?

Even before I realized the seriousness of our financial problems, I was determined to make improvements in our budgeting procedure. I was frustrated in my first year as President when I discovered that I could not understand the Dartmouth budget. Since I had more quantitative sophistication than most college presidents, I decided that the short-coming was in the system and not in me. Annual financial statements are designed for accountants whose requirements are quite different from those of the chief executive officer and the Board of Trustees. I discovered that I could not win the battle of accounting requirements, and therefore there was no alternative but to keep two sets of books!

Once we computerized our financial record-keeping system, this was not as horrendous a task as it might at first appear. We do not really keep two sets of books, but by careful coding of prime accounts we now produce our budget in two (or more) different forms, depending on the purposes for which it is needed. As a result, we have greatly improved our ability to make longrange plans and at the same time improved our ability to keep various departments of the College within their budget. For this achievement I must pay particular tribute to William Davis who, first as budget officer and later as treasurer of the College, carried the brunt of the burden. Instead of perennial budget overruns, which we would discover only several months after the books were closed, we now have a system of "early warning" that has kept most accounts within the allocated budget. In the last three years we have experienced in turn an over-run of a fraction of one per cent, a slight favorable outcome, and finally a significant favorable outcome, much of which must be attributed to more careful monitoring.

It has been traditional for the budget committee of the Board of Trustees to approve a budget for the next academic year in April. We also have established a new practice under which the Board reviews a four-year forecast at the October meeting. It is at this meeting that guidelines are established for the development of the next budget. With six months lead-time it is possible to take corrective action. This proved particularly important last year when, in the fall of 1974, it became clear that cuts of more than half a million dollars would be necessary to bring the budget into balance. (The figure finally arrived at was $725,000.) At best such cuts are painful, but given the cycle of the academic year, they would have been impossible six months later.

One important goal of the restructuring of the budget was to have each account under the control of one senior officer. It is the responsibility of this officer, usually at the vice presidential level, to monitor expenditures in his own area, to prepare the next set of budget recommendations, and to defend them in front of his colleagues. This has led to a systematic budget debate and a carefully thought out set of priorities before the budget reaches the Board of Trustees.

Even wider input into the budgeting process was provided by two groups representing the entire Dartmouth family. When we first faced serious budget problems, I established an ad hoc task force on budget and priorities which formulated a four-year plan that was approved by the Board of Trustees. At the time of a more severe budget crisis last fall, we were in the midst of establishing a permanent Council on Budgets and Priorities, which I described earlier. Dean Hennessey and his colleagues are providing an invaluable input into the budget process and a much-needed sounding board for debates on priorities. The devotion of the council may be measured by the fact that between the fall and winter Trustee meetings it had six half-day meetings within a month-and-a-half, and each council member served on two sub-committees that studied individual areas of the budget in great depth.

Let us examine the growth of the Dartmouth budget in more detail. I would like to compare the developments of the decade before I took office with those of the past five years, and have therefore asked the treasurer to prepare a presentation of the budgets for the years 1959-60, 1969-70, and 1974-75.

The accompanying pie-charts show the growth and distribution of the total institutional budget. One can see the dramatic growth of the '6os and some important shifts by categories.

Instruction and research has grown from 35.1 per cent to 42.5 per cent of the total budget. The major growth occurred during the earlier period when federal research funds were plentiful. Although these funds have been declining in recent years, the growth of the Medical School has more than made up for this.

Auxiliary activities represented nearly one-fourth of the total in 1959, which seems to me much too high, and there has been a healthy decline in the relative weight of these activities.

In 1959 we did not have Hopkins Center and we had barely entered the computer field. These activities together with the Tucker Foundation show up as an important component a decade later. Clearly, all three profited from the affluence of that period and have suffered a relative set-back in the past five years.

Since so much comment is heard on campus about administrative costs, it is interesting to note that while administration and student affairs is a slightly higher percentage of the total than five years ago, it is well below the 1959 level.

Some of the same trends may be observed in the set of revenue charts. Auxiliary activities, which we try to run at a break-even level, have declined dramatically. Sponsored activities, which include government-supported research projects, grew in importance for ten years but have since declined.

But the survival of any institution depends primarily on its "free funds," fees from students, endowment revenue, and gifts. I am surprised to see how much the relative importance of student fees declined during the '6os. We have made a partial recovery since that time. In spite of the spectacular growth of the earlier decade, endowment revenue kept ahead of growth, and the Alumni Fund and other gifts for current use assumed a new importance. This decade was truly a golden age. In spite of the new formula on endowment spending, endowment revenue has slipped in the past five years relative to the total budget, a trend that will continue for some time. Fortunately, the Alumni Fund and gifts for current use have continued to grow in importance; today these current use funds provide nearly as much revenue as the total endowment!

The table on the next page is designed to give a feeling for rates of growth. Since the major change in the Medical School can distort- the picture, its budget has been omitted from these figures.

During the '6os, the annual growth rate was 10.5 per cent, of which 4.3 per cent was accounted for by the combination of growth in enrollment and inflation. This means that there was an average annual increase of 6.2 per cent in spending per student, as measured in constant dollars. This enabled the College to improve salaries and to enrich the programs offered by the institution. Will we ever again experience such a period of affluence?

For the past five years enrollment growth and inflation combined for an average growth of 9.8 per cent per year, which is 2.4 per cent higher than the growth in the budget. That means that we have actually reduced the expenses of the College, per student, by more than ten per cent as measured in constant dollars. Part of the reason, of course, is the Dartmouth Plan. But very tight budget control has also had its effect.

Let us examine the various growth rates for the earlier decade. On the expense side one rate seems spectacular, and it reflects the fact that Kiewit, Hopkins Center, and the Tucker Foundation grew to their present importance during the '6os. One also notes spectacular gains in instruction and research as well as libraries, and the large increase in financial aid due in part to the equal opportunity program. On the revenue side the growth of sponsored activities is the dominant feature; this large increase in federal funds, combined with double-digit growth in endowment revenue, the Alumni Fund, and gifts, made the very rapid expansion of the budget possible. The picture for the last five years is quite different.

A word of explanation is needed concerning instruction and research. At first it appears that we have slighted the most important budget category. However, one must take into account that sponsored activities, most of which support educational or research programs, have actually declined. After making the appropriate correction, one finds that the support for instruction and iesearch from College funds has been rising at 11.6 per cent. This must mean that we have not only kept up, but have had to support out of free funds activities previously supported from the outside.

There are three other areas that have grown faster than the combined rate of student growth and inflation. One is libraries, which present a special problem discussed elsewhere in this report. The second is administration and student affairs, which I have also discussed elsewhere (this is the area from which the largest cuts will be made next year). The third rapidly growing area is plant, due in part to the large building program but even more to the terrible escalation of oil prices.

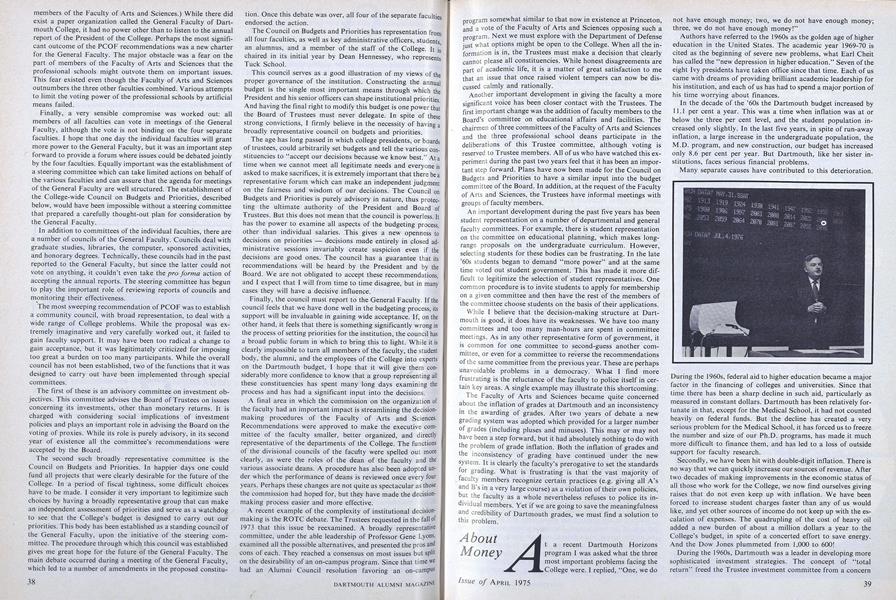

BUDGET GROWTH RATES Excluding Medical School (000 omitted) Annual Annual 1974-75 1959-60 Growth 1969-70 Growth Revised Expense Actual Rate Actual Rate Budget Instruction & Research $3 402 11.5% $10 130 6.6% $l3 940 Libraries 450 11.2 1 299 10.3 2 118 Kiewit, Hopkins Center, Tucker Foundation 50 45.8 2 169 3.4 2 568 Administration, Student Services and Misc. 2 000 9.3 4 849 10.6 8 031 Athletics 490 8.0 1 060 8.5 1 593 Financial Aid* 887 11.5 2 628 5.4 3 413 Plant 894 9.4 2 194 10.9 3 675 Auxiliary Activities 2 946 7.1 5 853 6.0 7 817 Total $11 119 10.5% $30 182 7.4% $43 155 Exclusive of Loans

Revenue Student Fees $4 239 7.5% $8 775 11.5% $15 103 Endowment Revenue 1 599 14.3 6 075 6.2 8 191 Gifts for Current Use 464 14.3 1 760 7.5 2 529 Sponsored Activity 680 18.4 3 670 (5.7) 2 733 Alumni Fund 422 17.5 2 117 13.6 4 000 Auxiliary Activities 2 881 7.1 5 736 5.7 7 584 Other Direct Revenue* 834 9.4 2 049 8.0 3 015 Total $11119 10.5% $30 182 7.4% $43 155

*Includes Athletic Revenue

The other expense categories have been held to slower growth, for financial aid perhaps too much so. While part of the slow growth in this category is due to the increasing importance of loans as opposed to scholarships, we feel that we may have made the change too rapidly, and in spite of budget cuts we plan a substantial increase in scholarship aid next year.

On the income side the increase in student fees has been important to the College. Part of the 11.5 per cent increase is due to an increase in the enrollment, but charges have had to rise more rapidly than desirable. The one income category that has continued its spectacular growth is the Alumni Fund.

One must bear in mind that the large cuts now planned are not shown in the table. Therefore, a further reduction in the costs of the College (in real dollars) is inevitable next year.

One question frequently asked is how much of the cost of education is covered by tuition. A precise answer is very difficult, but a rough estimate may be obtained by analyzing the free funds in the accompanying table. Student fees provide $15.1 million while the endowment, the Alumni Fund, and other gifts provide $14.7 million. Thus "full tuition" only pays for about half the cost of education.

Let us now look at our ability to raise funds for Dartmouth College. During the past five years, approximately $80 million was raised from private sources. (This included roughly $14 million pledged under the Third Century Fund.) The single most important factor, of course, has been the doubling of the Alumni Fund. Perhaps the secret of that extraordinary increase has been the reunion class giving program which has raised the sights of many potential donors. When I first took office, a single $15,000 gift led the list of donations to the Alumni Fund. In 1975 we already have a pledge of $l00,000 and several pledges of $50,000. A wonderful rivalry has developed among reunion classes to try to break previously established records. In this competition the honor may go to individual classes but the clear beneficiary is the College.

A great eal of credit for the tremendous success of the Alumni Fund goes to George Colton '35 and his associates. But the fund could not possibly achieve its fantastic success without the help of thousands of alumni volunteer workers and without the exceptional quality of the Alumni Fund chairmen with whom I have been fortunate enough to share my alumni tours.

The single hardest task facing an institution in the fund-raising area is the solicitation of major gifts. Since the Third Century Fund, our list of major gifts has been led by our very successful bequest program which has totaled more than $l5 million in gifts of $l00,000 or more. We have also been much more successful recently in approaching foundations outside of a capital fund drive. The Fairchild Foundation contributed more than $3 million to the science center. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has contributed more than a million dollars to the Medical School. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation has made significant contributions both to the Medical School and to our transitional costs for year-round operation. The Sloan Foundation, as reported elsewhere in the report, has made three major gifts to the College. The Luce Foundation helped us to establish an endowed chair in environmental studies, without which that extremely important interdisciplinary program would never have gotten off the ground. The Dana Foundation funded the expansion of the Dana Biomedical Library, the Bingham Trust has made a major pledge to Thayer School, and several other foundations have made donations of a hundred thousand dollars or more to support the ongoing efforts of the College. One that deserves special mention is the gift of the Ford Foundation for a presidential venture fund to be matched by the Trustees of the College. In a time when new initiatives are very difficult because we do not have enough money for all on-going activities, this grant has assured that $150,000 a year is earmarked for venture, which will be of enormous significance to the long-range welfare of the College. Dozens of individual donors have also made major contributions to the College, totaling some $4 million.

One of the important decisions Dartmouth will have to make during the next few years is whether it is necessary to launch a new major gifts campaign, or whether it is possible through reunion giving and solicitation for specific purposes to provide a sufficient continuing flow of money for the support of the College.

The Sloan study, already mentioned in this report, gave us considerable insight as to how our own budget compares with that of similar institutions. The study showed that our expenditures per student were at, or slightly above, the average for the nine institutions. The areas in which we were spending more than other institutions were precisely those areas to which the College assigned very high priority.

In a more detailed study, the nine institutions were divided into three groups of three: research universities, small universities, and liberal arts colleges. We fell into the middle group. In comparing ourselves with the two institutions most similar to Dartmouth, we concluded that our expenditures were "just right" in all but one area. The one budget area in which our expenditures were exceptionally high was the large and complex area called student affairs. Since I found the differences difficult to explain, I requested further details about the line items included in this budget area. The differences are due to two entirely different causes. One is the fact that Dartmouth College provides much more for its student body than its sister institutions. The Dartmouth Outing Club and the Tucker Foundation are two major line items that have no counterparts in the other budgets. Clearly, I am in favor of continued support of both those activities. But even when we made allowances for these differences, it became clear that our total budget for student affairs was out of line. For example, the student health service at Dartmouth, certainly one of the best in the nation, was far more expensive than that of the other institutions. Therefore, when we were forced to make significant cuts in our budget, it was natural to look to student affairs for the largest savings.

A period of financial stringency brings about a number of changes in an institution. Senior officers of the College spend a disproportionate amount of their time worrying about budgets. Other constituencies begin to question some of the priorities that have been assigned by the institution. The reins of management have to be held much more tightly. Although Dartmouth may emerge as a stronger and healthier institution as a result of several years of self-examination, no single factor could boost morale on campus more than having at least one year when we do not have to face a new financial crisis.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

MARCH 1964 -

Feature

FeatureTHE WHEELOCK SUCCESSION

DECEMBER 1969 -

Feature

FeatureThe Computer Goes Fishing

September 1975 By DARREL MANSELL -

Feature

FeatureAll the Way with J.B.A.

December 1980 By Frank Smallwood -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Sept/Oct 2007 By Kristine Keheley '86 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySolitary Family

MARCH 1995 By Rabbi Robert Schreibman '57