Coeducation was an issue on which men of good will who deeply loved the College could hold diametrically opposite views and firmly believe that they were right. They could and they did.

We know more about the attitudes of the various constituencies on coeducation than on any other subject. A professional survey by the late Oliver Quayle '42, taken of a carefully selected cross-section of the alumni, revealed the following facts. A majority of the alumni favored the education of women at Dartmouth in some form. On the other hand, no specific plan could come close to mustering majority support. Of the 40 per cent of the alumni who were opposed to any form of coeducation, more than half had extremely strong feelings on the subject. Furthermore, the alumni classes were split according to when they graduated from the College. The classes in the '20s were firmly opposed, the classes of the '6os were strongly in favor, and there were all gradations between. Although many tried to question the accuracy of Ollie Quayle's poll, various samplings I was able to make myself reassured me that he accurately reflected the opinions of the alumni body.

The constituency most strongly in favor of coeducation was the faculty, which came out nearly 10 to 1 in favor. The studern body was also strongly in favor, but with a vocal minority in opposition. One of the perplexities of the debate was illustrated by the student who claimed, "Everybody I know is opposed to coeducation" and another student who claimed, "Everybody I know favors coeducation". and they were both right. Friends tend to think alike, and having spent a great deal of time discussing this, controversial issue they reached the same conclusion. Similarly, groups of alumni with identical opinions found it difficult to believe that other alumni thought quite differently about the question. In short, this was potentially the most divisive issue facing the College.

The controversy started before I became President of Dartmouth. The Trustees had established a committee on coeducation co-chaired by the senior Trustee, Dudley Orr '29, and Leonard Rieser hen provost of the College. Three faculty members had been chosen to represent Arts and Sciences; I happened to be one of them. Our committee was hard at work throughout 1969, and we were ready to make the first public presentation of our tentative findings late that year.

December of 1969 will be remembered by many members of the Dartmouth family for the truly memorable Charter Day celebration. The Alumni Council rescheduled its meeting so that the members could participate in this historic event. By that time I knew that I was one of several serious candidates to succeed John Dickey in office, but I had no way of estimating my chances. I was therefore surprised when the president of the Alumni Council requested that I give the major report on coeducation to the council. I remember thinking that I had only two options: I could alienate half of the Alumni Council, or all of it. I told my wife that whatever chances I might have had to be chosen as the next President would evaporate after I gave that report

I was to learn an extremely important lesson on that day in mid-December. I would never again judge the alumni so unfairly; I learned that if one faces a group of alumni and tells them honestly and frankly what the issues are, and why people feel one way or the other about the merits of the issues, one gains respect even from those who totally disagree.

The following month, I was elected the 13th President of the College and my role changed dramatically. As one of the majority of the Trustee committee who favored coeducation, I faced a major challenge to come up with plans that would be in the best interests of the College, that would lead to as little bitterness as possible in the alumni body, and that could be approved by the Board of Trustees - without jeopardizing the financial well- being of the institution.

From my discussions with the Alumni Council it became clear that even alumni who favored the admission of women would not accept a large reduction in male students. Yet I was reluctant to follow the examples of Yale and Princeton in enlarging the student body significantly. A thousand more students on campus would require the construction of very expensive facilities and would result in a degree of crowding that would have a highly negative effect on the educational process. I therefore began to think seriously about the idea that we increase the total student body without increasing the number on campus at a given time. The idea was to add a fourth term to the academic calendar and spread a larger student body out among four terms. While I had no more than the germ of an idea, and two separate faculty committees would eventually have to put in enormous amounts of work to design a practical plan, I do not believe that the Trustees would have voted in favor of coeducation if it had not been coupled with the Dartmouth Plan.

I would like to acknowledge that I was wrong on another major issue confronting the Trustee committee - the form of coeducation to be adopted. A variety of options were explored ranging from building a women's college near Dartmouth, through some form of an "associated school," to full coeducation. On this issue I was prepared to compromise because I felt that an associated school would provide almost all of' the educational advantages of coeducation and would gain much wider acceptance from the alumni. The faculty voted overwhelmingly against that plan. In view of our experience in the past three years, it is clear that the faculty was right!

After all the arguments had been mustered on both sides, and all the constituencies had been heard from, the decision was up to the Board of Trustees. A special meeting of the Board was called for Saturday and Sunday, November 20-21, 1971. This was the most remarkable meeting of the Board of Trustees I have had the privilege to attend, and I deeply regret that we did not tape-record the session to make it available to future Dartmouth historians.

Besides all the material prepared by the Trustee committee, the Board had requested a variety of additional information. An important role was played by the consulting firm of Cresap, McCormick and Paget. They presented their review of the combined financial impact of coeducation and year-round operation, both short-range and long-range. They estimated that after transitional costs, and after the costs of some facilities modifications, the College could roughly break even, with the possibility of a modest additional expense or a very small net profit. Our experience has proven these estimates accurate; we have had a small addition to the net budget of the College, within the range predicted, and have reduced significantly the cost per student at Dartmouth.

The consultants also prepared, with the kind cooperation of Yale and Princeton, a confidential report on the experiences at those two newly coeducational institutions. The Trustees also had a survey of high school students indicating that our plan for year- round operation would meet with considerable acceptance, a prediction that has been borne out by the large increase in applications.

Two other developments might have had an effect on the Board's decision. The possibility had been raised that new federal legislation would make it mandatory for the College to become coeducational, and there was a fear that applications to Dartmouth might start declining as they had at other private single-sex colleges. The Board was informed that neither of these two events had occurred, and therefore it was under no compulsion to act in favor of coeducation.

Dean Carroll Brewster had been requested by the Board to consider alternative administrative arrangements, particularly as might be used to implement the "associated school" idea. He reported that following that route would mean substantial additional administrative costs and would significantly reduce the educational benefits of coeducation.

The most fascinating part of the Board's discussion centered on the question of the role of women in future American society. Several Trustees expressed the conviction that women would play an increasingly important role in leadership positions in the country. Therefore, they argued, Dartmouth, which had traditionally prided itself on the training of leaders, should train women as well as men for leadership roles. It was also argued that if, in the future, our male graduates would work side by side with women, we would be providing an unreal learning atmosphere in an allmale college. The argument that we prepare our students for "a man's world" may once have been accurate and persuasive, but it was no longer true.

The Board recessed late Saturday afternoon to give its members a chance to reflect overnight. I believe that none of us had much sleep that night. The Sunday morning session was a solemn one. All the arguments were over, and it was up to the Board of Trustees to decide the future of the College. Under the leadership of its chairman, Charles Zimmerman '23, the Board passed two key votes. It voted unanimously to put the College on year-round operation. It then voted - by a substantial majority but not unanimously - to matriculate women as undergraduate students starting in the fall of 1972.

The Board then turned to various implementing actions. Most important was the approval of the blueprint for year-round operation prepared by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Next was the question of the number of women students to be admitted to the College. The Board limited itself to setting a general guideline for the first four coed classes: the male student body should be set at 3,000 and as many women should be admitted as the Dartmouth Plan would allow. My estimate at the time was that this number could be as low as 900 or as high as 1,100. As it has turned out, we will have roughly 3,000 men and 1,000 women enrolled in the College next year.

Finally, the Board of Trustees voted to authorize the President to attract to Dartmouth a distinguished woman educator to help with the transition to coeducation. One of the academic administrators I had grown to like and respect most was Ruth Adams, president of Wellesley College. Dr. Adams had announced in September of 1971 that she would retire from Wellesley at the conclusion of that academic year. I was most fortunate in being able to persuade her to accept the position of vice president at Dartmouth. We agreed that she would serve fulltime for three years, and part-time for an additional two years, to help us with the problem of transition. Her long experience, her quiet advice behind the scenes, and her unshakeable good humor were invaluable assets to a group of male administrators, none of whom had ever had any experience at a coeducational institution. Our women students, faculty, and administrators are more in her debt than they will ever realize.

We had nine short months to get ready for both year-round operation and coeducation. It was an extremely hectic and very happy period in the lives of many of us. There was great excitement and anticipation on campus following the very lengthy debate. It is a good feeling to know that all of the arguments are behind you and you can finally go into action. During this period, we were mentally preparing ourselves for an endless number of problems that would no doubt arise from the major changes. The difficulties that have arisen in connection with year-round operation are discussed in the next section. But most of the anticipated problems with coeducation never materialized. I still find it difficult to believe just how smooth the transition has been.

Of course, there were some problems in the first year. It was hard to guess how many of our students wanted to live in singlesex dormitories and how many would opt for coed dorms. (We would find that dormitories with one floor assigned to women students would be particularly popular.) We were concerned whether the words of the alma mater would become a source of major debate. Women students opted for tradition and they became "Men of Dartmouth." There were some men in the upper classes strongly opposed to coeducation who seemed to feel it their obligation to express their resentment to the new women students. Most of them would change their minds when they got to know the women better, and the rest have fortunately graduated.

It was in the second year of coeducation that a long-time member of the Dartmouth faculty said to his colleagues, "This place feels as if we had always been coed." I have heard this remark quoted over and over again, with a considerable degree of approval. I have noticed increasingly that those who objected to coeducation in the abstract have found it very difficult to object to the women of Dartmouth. The male student body at Dartmouth had always had a distinctive character. We have discovered that women students come to Dartmouth for very much the same reasons that have made it so attractive for two centuries, and they are in a very real sense the natural counterparts of the men of Dartmouth. Their love for the College and their loyalty to the institution are - if possible - even greater than that traditionally shown by our male students.

I am confident that future historians will record that Dartmouth made the great change at the right time, and that it became a better educational institution for having done so.

Features

-

Feature

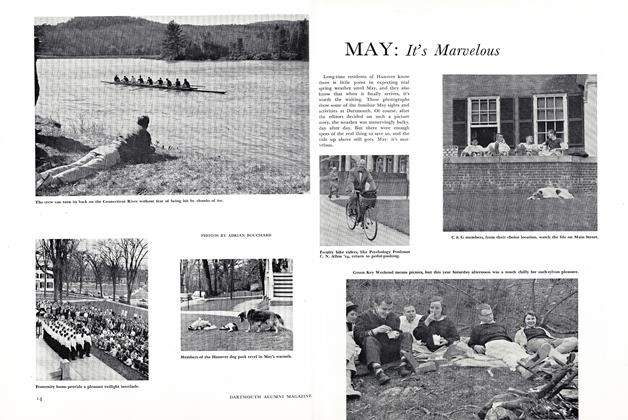

FeatureMAY: It's Marvelous

June 1958 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Debaters Are Arguing Themselves Into National Renown

March 1962 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Features

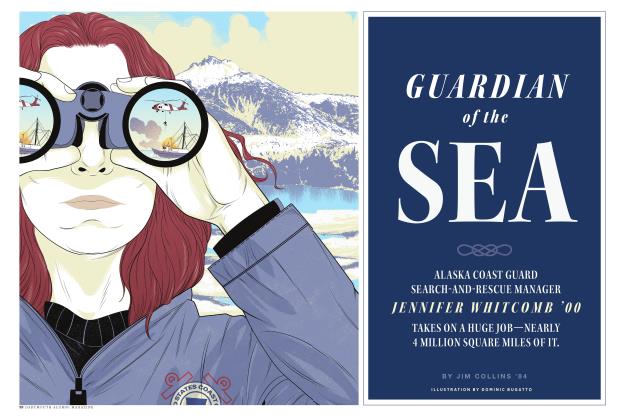

FeaturesGuardian of the Sea

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2025 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureCreative Art

MAY 1957 By PAUL SAMPLE '20 -

Feature

FeatureTHE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

MARCH 1964 By THOMAS E. O'CONNELL '50 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Lesson Tabled

MARCH 1995 By Ursula Gibson '76