By Elliott Adams White '12 New York: Pageant Press, Inc.,1968. 69 pp. $3.

Even in the Department of English noted for its versatility during the Hopkins era, Professor White was conspicuously protean. In 1916 he was an infantry sergeant in Texas and in World War I a civilian senior inspector of Military Materiel with the U.S. Signal Service. He was educated at Dartmouth, Harvard (summa cum laude, 1912), Missouri (M.A.), and Michigan (Ph.D.). At Dartmouth he taught both English and Physics, and he also taught at Radio Naval Auxiliary School, the Carnegie Institute of Technology, Pittsburgh, and Northwestern University. During World War II he was an electronics designer for Raytheon and again in 1951-53. His hobbies have been radio, hi-fi, astronomy, languages ancient and modern, wine making, Europe (1200 miles with a pack on his back in England), the Far East with a minimum of luggage (he studied Chinese for two years), the world by freighter, tobacco, and a Winnipesaukee island. A recluse now living alone back of Norwich somewhere, he is never seen in Hanover.

Now going on 80, Professor White has written poems academically eclectic but nonetheless lyrical. He favors Latin titles: "Dies Pluvialis," "Carpe Horam," "Naturae Verus Amors," "Omnia Quiescunt," "Summa Felicitas Brevis Est," "Grata Vice Veris Et Favoni." Against a Vermont background he concentrates on illusion and loneliness, beauty and birds, lost love and eternal desire, time and the soul, senescence and death.

These are indeed romantic themes, but Professor White writes with freshness and originality. "A hundred things don't love an open field" sounds a little like Robert Frost, and so does "Winter's the time for pleasant loneliness" unless you wish to insist on William Cowper. Introductory lines leading to a warm appraisal of two eccentrics sound a little like Edwin Arlington Robinson. ("This day, five years ago, we lost Ed Rolfe" and "Bill Blunt has passed at last to his reward,") unless you wish to insist on George Crabbe.

But White cannot be so narrowly measured. With a Japanese Haiku he can reduce his own poem of six lines and 45 words to two lines and 15 words: "The only daisy I see in the meadow / Is the one a shadow passes over." Catullus leads him to lament a Professor as "martyred hero." He is himself with "Me now, when slower paced, the long hexameter; / The leisurely deliberately Alexandrine slow," which temporarily he Prefers as "diapason for my spirit's mellower tone."

Mellowness is one's abiding impression. Inexorable time does not embitter him, for its compensating cycle never fails. If light goes one way, day comes the other. In the winter of his age, he will not complain of winter sun or snow, for "There is a clearness in the wintry air; / There may be clearness in a snowy head."

The lyricist has visual acuity. In the perennial struggle of a farmer to keep his meadow free of weeds, the poet sees and names no fewer than 23 intruders. Then the wry ending: "...if he turns his back the field is gone."

But flowers, the sky, and adjustment to nature and time are the White imperatives. Part of his life, he tells us, was the seed of books. Then he reaped the crop of his labor. Part was "oats, both wild and straw/ But the best of my life was fallow."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

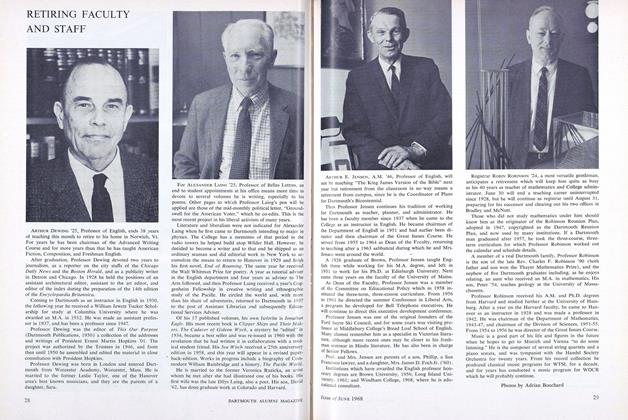

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY AND STAFF

June 1968 -

Feature

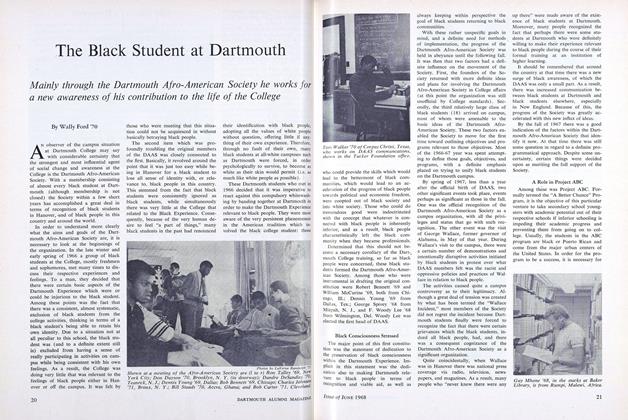

FeatureThe Black Student at Dartmouth

June 1968 By Wally Ford '70 -

Feature

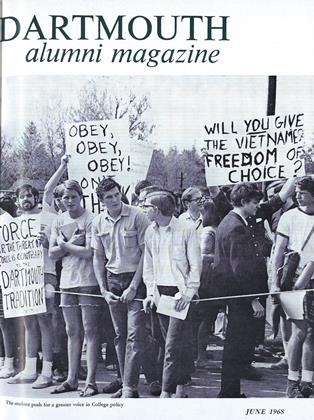

FeatureVox Clamantis 1968

June 1968 By Chris Kern '69 -

Feature

FeatureFour Steps Forward in Biology

June 1968 By PROF. RAYMOND W. BARRATT. -

Feature

FeatureShark Authority

June 1968 -

Feature

FeatureHeart Specialist

June 1968

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

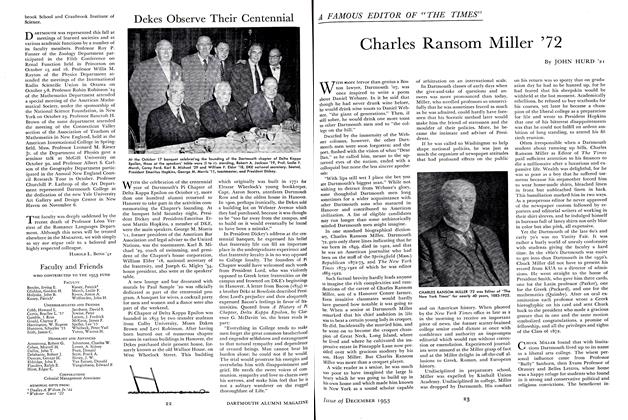

ArticleCharles Ransom Miller '72

December 1953 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC.

June 1961 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksPAGE 2, THE BEST OF "SPEAKING OF BOOKS" FROM THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW.

FEBRUARY 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksJOHN MILTON. PARADISE LOST, PARADISE REGAINED, AND SAMSON AGONISTES.

MAY 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksFurther Mention

MAY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksVice in Its Gayest Colors

June 1975 By JOHN HURD '21

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE NEW ARGONAUTICA

December, 1928 -

Books

BooksRECENT RELIGIOUS LITERATURE

January, 1930 -

Books

BooksTHE MANUAL OF CORPORATE GIVING

November 1952 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Books

BooksPERSPECTIVE IN FOREIGN POLICY

JANUARY 1967 By HENRY W. EHRMANN -

Books

BooksDID THEY SUCCEED IN COLLEGE?

October 1942 By Louis P. Benezet '99 -

Books

BooksPAYMENT FOR PAIN & SUFFERING: WHO WANTS WHAT, WHEN & WHY?

MAY 1973 By MICHAEL L. SLIVE '62