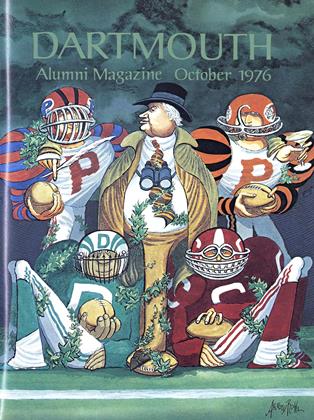

BACK in the middle of the 1973 season, Dartmouth's defensive unit was honored en masse after its three goal-line stands preserved a 24-18 victory at Harvard. Considering that the then stalwarts were people like Rick Gerardi (five-feet eight, maybe 185 pounds after a very big meal) and Tom Csatari (he looked more like a pencil neck than a three-time all-Ivy League defensive end — which is what comes from being weaned on the stones and crushed glass of North Jersey playing fields), you can appreciate why the label "Misfits" was hung on this assorted collection of sophomores and seniors.

It was a tag they found offensive and their inspiration was to prove it was undeserved. In some corners you could see the chipped shoulders and when they had helped put the finishing touches on six straight wins and Dartmouth's fifth consecutive Ivy championship, the message about what you could do with the nickname flashed in their eyes.

Well, something similar is happening this fall, only there's a different twist to the tale. For the past couple of years, the focus has been on the defensive superstars — Reggie Williams and Skip Cummins, holdovers from the 1973 corps. When they departed last June, the obvious question was, can Dartmouth fill the void? If two games are a legitimate gauge, the answer is: very nicely, thank you.

Permit this measure: on any Dartmouth football team you'll find a good group of people, but very few have produced the special something that seems to be the mark of the 1976 squad. Conspicuously absent are the maladies that are virtually unavoidable when you put nearly 100 aggressive personalities into the same boat. Missing are the subsurface frictions, the latent jealousies and pressures that you never hear about but which blunt the pursuit of peak performance.

In the purest sense, this is a team, and that is its greatest strength. From a standpoint of raw talent, it's better than either of its two immediate predecessors but it can't compare with any one of the 1969-72 teams that overall won 32 games, lost three, and tied one. For that matter, there isn't a team anywhere in the Ivy League this fall that can stand such comparison. That doesn't mean that Dartmouth's football team will be any less interesting or exciting before it wraps things up at Princeton on November 13.

Whoever penned the line "United we stand ... must have had Dartmouth's current football team in mind. To borrow a phrase from Tony Lupien, they've got "the thing." Ask not what it is, just be grateful that they've got it. It's a remarkably close-knit group and the reason for that is the leadership that has been generated by the captains, Kevin Young and Pat Sullivan. They are stronger in 1976 than they were when they led their freshman team in 1973, and the singlemindedness of this team flows to every man.

"It's nothing the coaches have done," says Rick Taylor, who directs the linebackers. "It's just the way these guys react to one another. They really pull for each other. There's no rivalry between offense and defense. You couldn't have seen a more collective letdown than the day [senior defensive end] Marty Milligan was hurt. You didn't see it, but you knew that every player, somewhere inside, cried for him, and they did it again later that same day when [tight end] Jim Darnell was lost. It's a nebulous thing. It's the nature of these kids. They care about each other and they mean it."

That's what made the opening game of the season, a 20-0 victory over Pennsylvania, something special. It was a game won with mutual contribution. The offense, under the direction of Kevin Case and demonstrating that Jake Crouthamel's sprint option attack works just fine with the benefit of backfield quickness and a strong, young line, tapped Penn for nearly 350 yards of total offense and never was in trouble even though its point production was limited to a pair of field goals by Nick Lowery.

Most of the scoring belonged to the defense. Two of the seven players who were either starting their first game or playing at a completely new position got the touchdowns. John Carney and Jim Vailas, juniors who play halfback and linebacker, can live with the memories of respective scoring runs of 61 and 35 yards with a punt and an intercepted pass. It was a team victory, and there was no question within the squad that game balls should be presented to the men who won't play a minute this season — Milligan and Darnell.

The next Saturday, against New Hampshire, the offense got all the points for a 24-13 win.

About the defense: while the 1973 team looked with disdain at anyone who mentioned their unwanted nickname, the 1976 defenders have already been tagged as a gang of no-names. Actually, that's not true because they've given themselves a name, Lurch and the Munchkins. There are ten Munchkins and Lurch is Gregg Robinson, the six-foot six 245-pound tackle whom Penn never was able to block effectively. For starters, Robinson had ten tackles, recovered a fumble, deflected two passes and twice sacked Penn quarterback Bob Graustein.

Robinson took offense at'being named a Munchkin, a name that surfaced during the variety night skits at the end of double sessions. The other ten starters were legitimate candidates, ranging in size from 170-210 pounds — hardly the credentials one expects to find in a major college defensive lineup. While Lurch stands out, a glimpse at some of the Munchkins reveals something about the whole business of togetherness.

Vailas, the middle linebacker, sat and watched Williams last season. "It was frustrating but I learned a lot, especially patience," he says. "I'm not as good as Reggie and never will be. No one on this team is that good. Last year, if we got in trouble, we looked for Reggie and Skip to bail us out. This fall, we help each other. I need Kevin [Young, the rover] and Kevin needs me. We know we can't do it alone."

Kevin Curley was a starter at outside linebacker as a junior and expected to be there again this fall — until Milligan was injured. His experience made him the choice to move to the front line. "He's playing a position he really doesn't like," according to Taylor. "We needed him and he knew it. It's tough for a senior who's been taught to drop back and protect against the pass to start charging the passer."

Steve Cordy, whose varsity career has seen him play linebacker and fullback, is the other end. It's something new for a guy who had to contend with assorted injuries and never really found a home — until now. Bill Jarrett, the short side linebacker, nearly packed it in as a sophomore. Something told him to hang in. He did and now he's a regular. The guy who works beside Lurch is Dave Casper.. At 205 pounds, he has no business being a defensive tackle, but he won the job a year ago and no one is about to take it away from him.

The littlest Munchkins are supposed to be in the secondary and outside of Dave Van Vliet, the experienced halfback, the rest fit the description — Carney, Dave Taylor, a five-foot nine safety, and Mike Metcalf. The symbol of all the Munchkins, though, has to be John Mugglebee. When he was invited back for practice in 1975, it was as much for squad morale as anything. "He wanted to be a part of the team," says Taylor. "We never expected him to do anything and he became a linebacker because we had an opening. He worked and he learned and when Curley was moved, J.D. had himself a job."

Mugglebee's dimensions are 5-10 and 170. He lines up to the open side of the field. His position demands the ability to work against a burly tight end or protect the perimeter. Eventually, he could lose his position to Jeff Hickey, a rangy sophomore, or to Wally Morgus, converted from the offense. Both are bigger but neither has Mugglebee's understanding of the position. At least not yet.

There's a candidate for honorary membership in the Munchkins on the offensive unit, too. Kelvin Hardy is a five-foot seven 149-pound sophomore. "That guy's going to get killed," an observer at practice noted one day. "No, he won't," said Crouthamel, who moved Hardy to flanker where he wouldn't have to contend with oversized traffic. "Kelvin's got no business playing football except that he wants to," observes John Curtis, the backfield coach. "He has no fear and you have to respect a man for that. He's doing what he wants to do — he's contributing to the club."

The atmosphere generated by this team has had its impact on Crouthamel, too. Dartmouth's coach seems more relaxed these days; if you don't believe it, you should have been on hand the day Bobby Riggs was in town. The tennis world's chauvinistic senior citizen visited Chase Field, and Crouthamel called an unscheduled break in practice for the first time in six years. Even Jake had to smile as the little man uncorked a mini-pep talk, threw a couple of passes to split end Harry Wilson, and ran the belly option with Curt Oberg.

Like we said, it's an unusual team that may wind up with a season remembered for many things. Including Bobby Riggs.

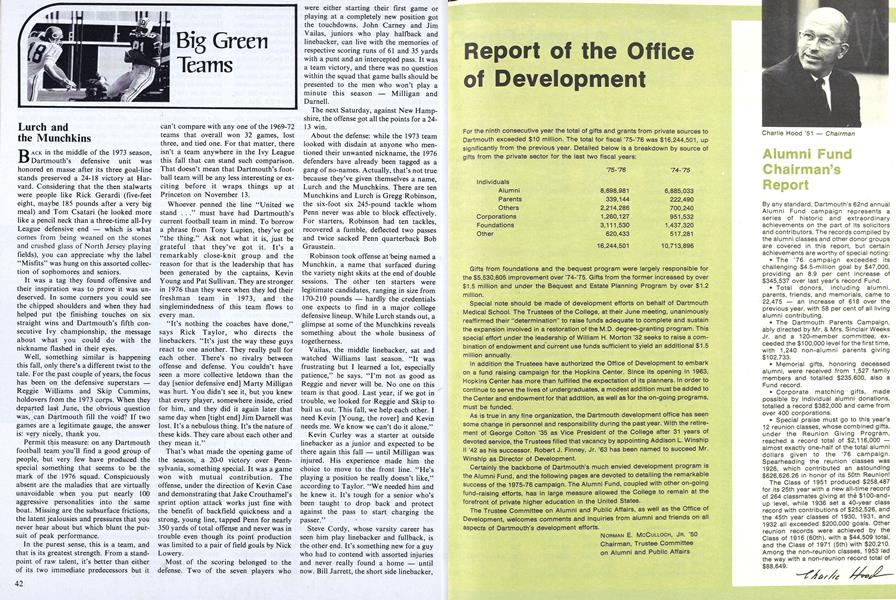

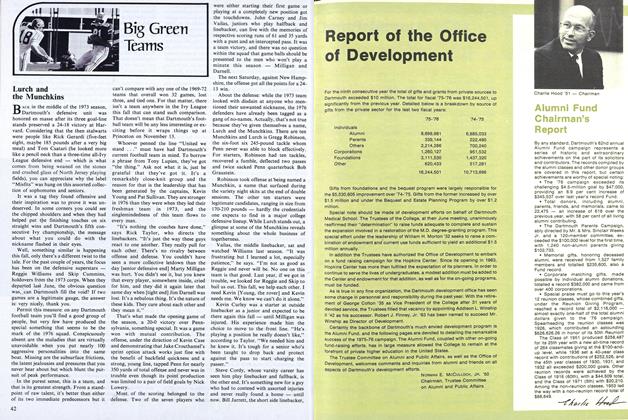

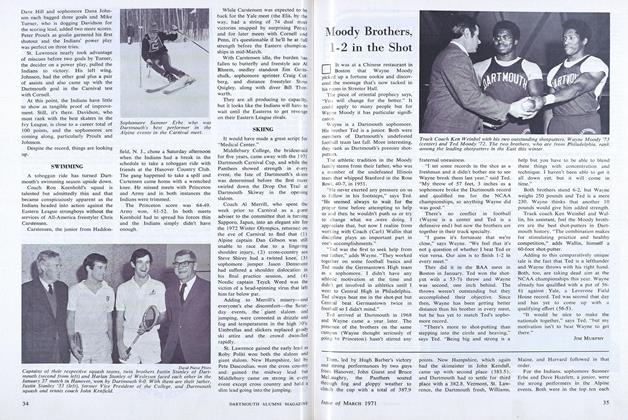

Munchkins Jarrett (24), Young (50), Vailas (56), Cordy (40), and Carney (behind Young)indulge in end-zone congratulation after Vailas' interception against Pennsylvania.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE IVORY FOXHOLE

October 1976 By JEFFREY HART -

Feature

FeatureMENAGE A HUIT

October 1976 By ROGERS E. M. WHITAKER -

Feature

FeatureRED BALLING IN THE JERSEY NIGHT

October 1976 By Jeffrey Brodrick -

Feature

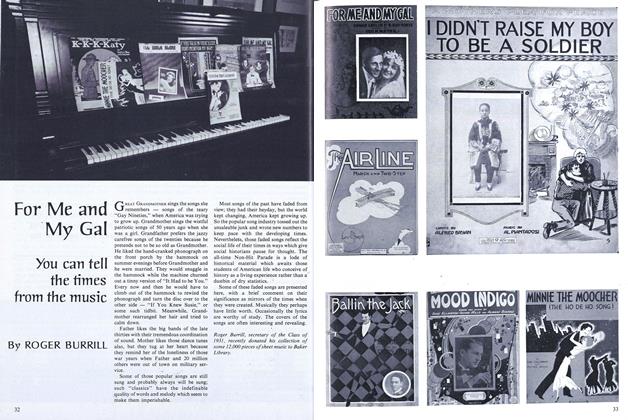

FeatureFor Me and My Gal

October 1976 By ROGER BURRILL -

Article

Article'My Own House'

October 1976 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

October 1976

JACK DEGANGE

-

Article

ArticleSports Schedule

JANUARY 1970 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN REPORT

JANUARY 1970 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleBASKETBALL

FEBRUARY 1971 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleSWIMMING

MARCH 1971 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

Article"More"

February 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Feature

FeatureYesterday's Glories Tomorrow's ?

JUNE 1977 By JACK DeGANGE