The plot line is uncomplex. A cultured, conservative insurance executive, Karl Muhlbach, middle-aged and a widower, falls deeply in love with a hip 20-year-old girl, Lambeth Brent, extravagantly beautiful but also paranoid and self-destructive. The place, New York City; the time, now; the result, disaster. The novel ends with her suicide. An uncommonly skillful story-teller, Connell moves his plot along with the deftness one expects of a celebrated contemporary novelist writing his 11th book of fiction.

But to leave it at that is a little like saying that The Canterbury Tales is the story of how an assortment of religious pilgrims whiled away their time on a tedious journey. For the essence of the novel - its experience, if you will - lies otherwhere than in what happens and when. A mere modern reworking of the January-and-May dilemma Connell's novel most definitely is not.

Implicit in what happens is his reading of why it happened. Fleetingly at first, then more persistently, the theme emerges: the anomie of modern life turns us inward upon ourselves, there either (like Muhlbach) stoically to endure or (like Lambeth) miserably to perish. Given the gigantic impersonality of contemporary urban existence, no indissoluble human relationship seems possible, least of all love. Like Lucretius's atoms, Connell's characters are propelled in incessant motion by forces beyond them, meet, collide, adhere momentarily, then veer off on their own orbits never permanently to join. The irreducible isolation of each human creature: the theme is not unfamiliar. Indeed, well over a hundred years ago Matthew Arnold used a metaphor different from Connell's, but to the same effect:

Yes! In the sea of life enisled, With echoing straits between us thrown, Dotting the shoreless watery wild, We mortal millions live alone.

If the experience of this novel does not inhere in its plot, however, neither is it wholly comprised by its theme. There are also important dimensions of character and craftsmanship. Connell is a superb stylist, "a writer's writer," as one critic observed, who writes with rare grace and economy. More important, he causes the very structure of his novel to reinforce, its theme. Double Honeymoon is composed of a series of more or less fragmented scenes, points and counter points, vivid vignettes one after another which by their very disjunctiveness embody and demonstrate the point: we mortal millions live alone, fragmented, in- complete.

The protagonist Muhlbach seems to have been conceived as something of a latter-day J. Alfred Prufrock. Revealed chiefly, like Prufrock, through the device of the interior monologue, Muhlbach too habitually travels certain half deserted streets of the mind, inhabits the party rooms where the women come and go, and, with the same middle-aged bald spot in the middle of his hair, has come to know that he is not Prince Hamlet nor was meant to be. For all his self-searching, however, Muhlbach not only commits himself to love but to a love which, with acute self-knowledge, he knows to be impossible. The Love Song of Karl Muhlbach ends in disaster, as he sensed it would. Disaster and, for the reader, pathos.

And the all-pervasive sense of anomie remains. At the end Muhlbach reflects on Lambeth's suicide:

There's absolutely nothing I can do. Nothing. Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow and there's nothing I can do....

So, having spread his umbrella and turned up his collar, Muhlbach steps outside to join the crowd. And presently, if seen from a distance, he could not be distinguished from the rest.

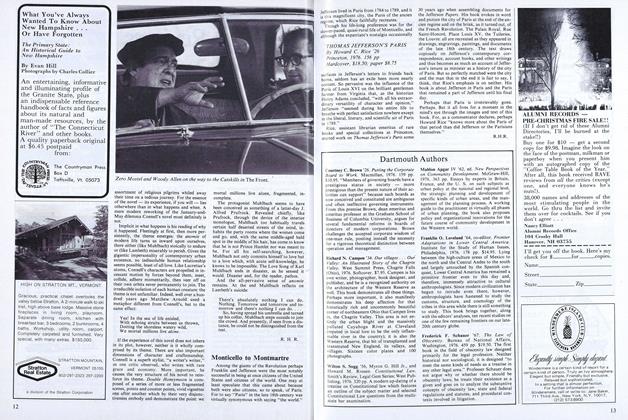

Zero Mostel and Woody Allen on the way to the Catskills in The Front

DOUBLE HONEYMOONBy Evan S. Connell Jr. '45Putnam, 1976. 252 pp. $7.95

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

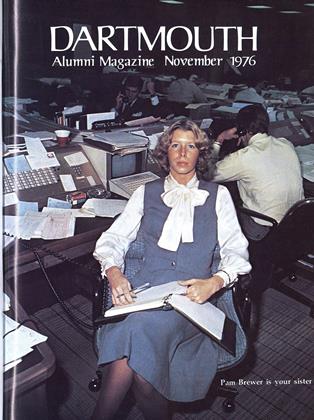

FeatureJUST LIKE THE REST OF US

November 1976 By A. KELLEY FEAD -

Feature

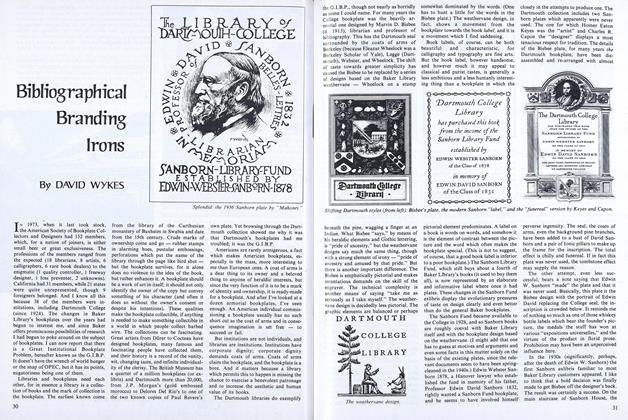

FeatureBibliographical Branding Irons

November 1976 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureThe and the

November 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureFive Deadly Threats

November 1976 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticleEight-y!

November 1976 -

Article

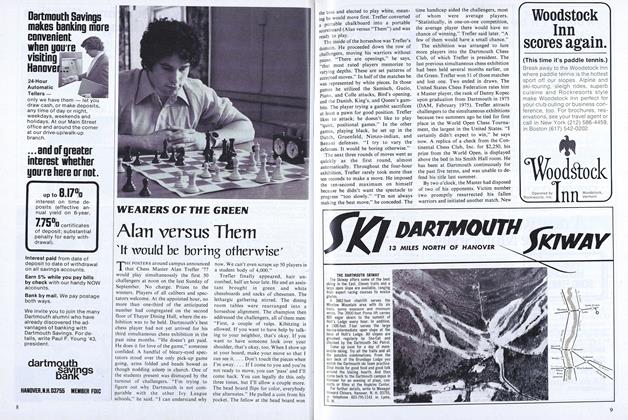

ArticleAlan versus Them 'It would be boring otherwise'

November 1976 By PIERRE KIRCH'78

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on some gentlemen songsters, with an aside on "antique and toothless alumni"

December 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksSeeing Tilley Plain

OCT. 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksOut of the Night

November 1978 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksLooking Out for #1

September 1980 By R.H.R.

Books

-

Books

Books'The Detroit Money Market'

May 1933 -

Books

BooksHOW TO SUCCEED AT TOUCH FOOTBALL.

MARCH 1963 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksCANCER: DISEASE OF CIVILIZATION?

March 1961 By DR. HENRY R. VIETS '12 -

Books

BooksHOW TO WRITE A MOVIE

January 1937 By Ernest Bradlee Watson '02 -

Books

BooksAVALANCHE OF APRIL

December 1934 By Franklin McDuffee'21 -

Books

BooksRELATION OF FAILURE TO PUPIL SEATING.

December 1932 By W. R. W.

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on some gentlemen songsters, with an aside on "antique and toothless alumni"

December 1976 By R.H.R.