Whatever happened to literate humor? It "is alive and well," Burton Bernstein answers, "just harder to find, that's all." Bernstein should know - he has been a staff writer on The New Yorker for 20 years - and to make his point he has collected 33 examples of that short form of literate humor called the "casual."

Together they make for a triumphantly funny book. But the book does not lack for nostalgia either, particularly for readers old enough to have seen Eustace Tilley plain and to have lived their vealish years in the age of the casual giants: Benchley, Thurber, Wolcott Gibbs, Perelman, E. B. White, and the rest who flourished in the glory days of The New Yorker and who, in mastering the casual, Bernstein concedes, "perfected the ultimate weapon in literate humor."

Alas, no Thurber, no Benchley, no Perelman. The Grand Masters are nowhere represented in this collection. E. B. and Catherine White's Subtreasury of American Humor has already collected them. And so Bernstein confines his anthology to the newer generation of humorists such as Woody Allen, Roger Angell, Donald Barthelme, Mark Singer, John Updike, and Bernstein himself. But one constant remains in a shaken world: the majority of Bernstein's contributors, like their predecessors, are either staff writers for or publish regularly in - what else - The New Yorker.

The word "casual," as describing a genre of literate humor, is not without some irony. For as the editor explains, the casual is "a seemingly offhand kind of work, constructed with such cunning that it appears to have been born whole, effortlessly and spontaneously - what the Italians call sprezzatura." The truth, however, is precisely the opposite. There is no reason to assume that language is any less obdurate, imagination any less stubborn, for the writer of humor than for any other kind of writer, or that the casual is any less difficult aborning than any other literary form. The successful creation of artifice comes hard. Indeed, a First Law of Satire - the Jonathan Swift Hypothesis, dare we call it? - might be posited something like this, the more credible the appearance of offhandedness, the more the sweat required to produce it. Put another way, literate humor is a rapier, and he who would take up the sword must die a little to make the point. Thus, then, with the casual: "It is often sheer hell," as Bernstein confesses, "to get one down on paper."

But you would never know it to read this book. Woody Allen's uproarious exegesis of The Scrolls," or his explication of a modern Irish poem from The Annotated Poems of SeanO' Shawn (an ego-deflater strongly recommended to over-solemn Yeats or Joyce scholars); Gordon Cotler's "My Stay in an American Hospital" (a dispatch to the People's Republic of China by Li Chin Tao, newly accredited American correspondent of the Peking Evening Star); or Bernstein's own word-game casual, "Look, Ma, I Am Kool!" (read the whole thing either backwards or forwards): Wherever you choose to start in this book, the donee, the unstated assumption as between writer and reader, is the same. "The reader should suspect," says Bernstein, "that the writer, while, say, brushing his teeth one morning, was visited by afflatus and, after a quick stop at his typewriter, was blessed with the finished article before his first cup of coffee was consumed."

Never mind that we know differently. Never mind even that analysis suggests a faint whiff of midnight oil and the creator's sweat behind his coolly insouciant creation. Never mind any of that. (Analysis and humor have always been like oil and water anyway!) What counts is the fun. We will go along with his givens. Gladly. Because if we don't we miss all the fun.

And this book is simply one hell of a lot of fun.

LOOK, MA, I AM KOOL!and Other CasualsBy Burton Bernstein '53Prentice-Hall, 1977. 238 pp. $8.95

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

October | November 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Singing of the Cider

October | November 1977 By Sanborn Brown -

Feature

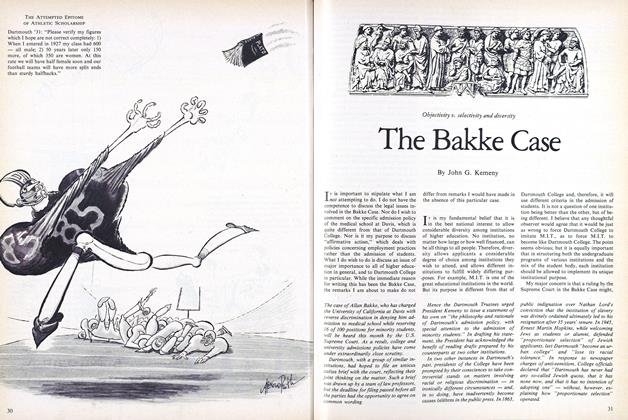

FeatureThe Bakke Case

October | November 1977 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureWith Pen In Hand...

October | November 1977 By Arnold Roth -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October | November 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Article

Article"My hardships were excessive"

October | November 1977

R.H.R.

-

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

May 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on some gentlemen songsters, with an aside on "antique and toothless alumni"

December 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksBound by Emotion

NOV. 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksObserving Life

JAN./FEB. 1978 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksThe Country Remembers

December 1979 By R.H.R.

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

December 1934 -

Books

BooksPERSPECTIVE IN FOREIGN POLICY

JANUARY 1967 By HENRY W. EHRMANN -

Books

BooksTHE PAPERS OF DANIEL WEBSTER. CORRESPONDENCE, VOLUME I.

January 1975 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29 -

Books

BooksGRAMATICA ESPANOLA DE REPASO.

July 1958 By JOSEPH B. FOLGER '21 -

Books

BooksHALL'S LECTURES ON SCHOOL-KEEPING

MARCH 1930 By R. A. B. -

Books

BooksTOMORROW'S BIRTHRIGHT.

January 1956 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29