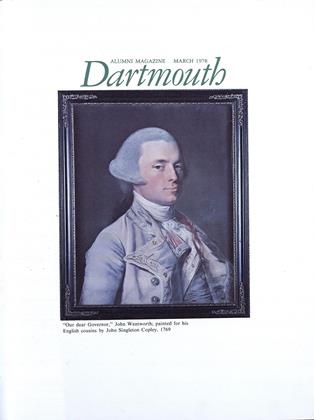

"Saturday Ist October. The weather, as usual in Hanover, gloomy and unpleasant. Hitherto, the sun has shone upon us only part of one day. I do not wonder at it, however, as Nature, here, wears her most horrid garb."

The year is 1808. The speaker is William Tully, Yale 1806. The complaint is familiar.

The young man (later to become Dr. William Tully, M.D. Yale 1819) was in Hanover from September through December, to attend a course of medical lectures given by Dr. Nathan Smith, founder of the fledgling Dartmouth Medical School. Tully's sojourn lasted a scant three months, and he was as delighted to leave Hanover as he was dismayed at what he found there.

Fortunately, Tully was an assiduous recorder, and he left behind an amusing journal of his days and ways among the curious natives of this rude New Hampshire outpost. Recently uncovered among the Yale University archives, the journal has now been published as a contribution to medical history (Oliver S. Hayward and Elizabeth H. Thomson, eds., The Journalof William Tully, Medical Student at Dartmouth, 1808-1809. Foreword by John F. Fulton. N.Y., Science History Publications, 1977. 88 pp. $15.00).

The book reveals something of the quality of early 19th-century medical education, much of the illustrious Dr. Nathan Smith, but even more of Hanover 170 years ago. But caveat lector! Both nature and nurture made William Tully a decidedly biased observer. His journal shows him to be, among other things, utterly humorless, indeed not without a touch of the prig. And as an observer of the Hanover scene, he never quite escaped the limitations of being a Yale man. Even one of his editors concedes that Tully was "a provincial, opinionated and pious young man not exactly devoid of... 'the elbowing self-conceit of youth.' "

Whatever the reality may have been, through Tully's eyes Hanover in 1808 appeared "a paltry little village, in which the College never ought to have been placed," cursed with the most wretched weather in New England, and endowed with a group of citizens who were to a man parsimonious, mean-spirited money grubbers. The first he encountered was one Amos Dewey, landlord of Dewey's Tavern (on the northwest corner of the Green) where fresh from the exalted purlieus of New Haven and Hartford Tully climbed down from his stage on a chill September evening. He found "a sour landlord, and a very dirty bar room full of persons of all descriptions," and though he and his companion "made shift to put up with much incivility before and during supper," they quickly resolved to search for more suitable quarters.

The search led only to further disillusionment. For Hanover landlords, it seems, were not only "sour" and uncivil; they were also rent gougers. "After application at every possible place, we were unsuccessfull, for either every room was engaged, or occupied, or those that intended to rent chambers were keeping them until the demand should be greater in hopes of an unreasonable price."

The residences of Hanover also failed to meet the standards of one accustomed to New Haven amenities. The house in which Tully finally found permanent quarters was "a large, two-storied, gambrel roofed building, that had been left, externally, in such an unfinished state as to be, at this time, quite shabby. It was glazed in but one or two rooms; and this had not been done till some individual had occasion to inhabit them."

As to the general aspect of the Green, Tully conceded that Dartmouth Hall was "a neat and really handsome building, and as well situated as it can be in Hanover." For other structures, however, he had scant praises. The chapel (in front of Dartmouth Hall to the southwest) was "a square, two-story house with quite a flat roof which very much disfigures the appearance of the College. Directly south of the Chapel stands the President's house, which is neat, not elegant. On the north side of the green stand two handsome dwelling houses and a decent church. On the west, the most elegant house in town. These, with two or three stores and a few other, shabby, old broken-windowed buildings, make the place."

The Hanover hills, along with the haphazard clearing of the Plain 'and surrounding areas of their primitive massive pines — apparently done largely by burning — also offended the eye of the young man accustomed to the wider vistas of Connecticut. "The horizon was very circumscribed; and on which side soever I turned my eyes I beheld hill on hill, rising above another, all covered with trunks of large trees over which the fire had passed. What was called the Hanover Plain ... was variegated with burnt shrubs, rocks and stones, Virginia, and crag-fences."

But his self-imposed exile, though dismal, was not entirely intolerable. He was unstinting in his praise of Dr. Smith and his new medical school — though only after he had accustomed himself to the Doctor's "extemporaneous" and "colloquial" manner of lecturing which, he thought, showed a certain "lack of elegance." And although he avoided close association with Dartmouth undergraduates — whom he considered bumptious, ill-mannered "Hantonians" — he managed to find a small circle of friends equal to his standards: primarily "Connecticutensians and those few graduates from Harvard and Yale that are occasionally under Dr. Smith's instruction." This group boarded at the home of Caleb Fuller, which displayed "the most taste of any situation in Hanover," Tully wrote. "The fare is such as is to be found in the best boarding houses in New Haven and Hartford; and the same order of politeness is maintained as is to be found in every well ordered family in any of our larger towns." But Fuller was "a native of Connecticut and a graduate of Yale-College; and hence his manners and those of his family ... are totally different from anything around them."

Tully was not averse to joining an occasional stag party, for which apparently his Yale education had afforded some precedent. At one such party a group of 30, most of them members of a society of medical students, were served cold tongue, cake, crackers, cheese, and liberal potions of brandy and water, after which "all were removed and glasses of wine were brought. A multitude of merry toasts were drunk, a great variety of songs of every sort were sung, . . . and the evening was passed in social hilarity. Just about eleven o'clock the noise of a violin was heard in the house." The violinist was called in, "the table removed, and though we wanted the assistance of ladies, yet we contrived as it was to dance an hour or two. . . . Toward one we retired."

As for the College and its faculty, Tully was disapproving but not unduly severe. He admired Eleazer Wheelock (by reputation); Roswell Shurtleff, the professor of theology; and of course Dr. Nathan Smith. He censured the faculty's lax discipline in failing to compel the undergraduates to study; he found Samuel Zyre, a tutor, "a dirty fellow" (literally, one presumes); and he deemed the public prayers of President John Wheelock to be "mere bombast" full of "the turgid, the verbose, and the pompous." At bottom, however, the trouble with Dartmouth was that it was not Yale, "I wonder how many times... I have made and shall make comparisons between Yale and her faculty and Dartmouth, and hers; and invariably to the disadvantage of the latter." But, he adds. "I suppose I should be thought prejudiced by people in general." Heaven forbid, Mr. Tully!

It is for the townspeople of Hanover, particularly its merchants, that Tully reserves his most trenchant judgments. "If the inhabitants had even possessed one single spark of manhood, or enterprise, they might, honourably, have become rich from the wealth that the students, and the collegiate festivals, had brought into the place." But no, they were instead "a people calculating to live as parsimoniously as possible, without any regard to the comforts of life — to entertain a stranger as miserably as he will put up with, and for the greatest possible price that can be extorted from him — too lazy to make any exertions on their own but depending entirely upon the College for support; and withall too ignorant to have any idea of a better possible mode of life."

And then of course there was also that plaguey weather. On December 29, the happy day of his departure from Hanover, "hitherto, not a flake of snow had fallen, but now there was a violent storm." By the time his stage had reached Windsor "it had fallen to a depth of two feet. ... It was excessively cold."

Farewell, William Tully. Bon voyage!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

March 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

March 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureNEFERTITI

March 1978 By Ray W. Smith -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

March 1978 -

Article

ArticleAn Untraditional Path

March 1978 By A.E.B. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1978 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR.

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on some gentlemen songsters, with an aside on "antique and toothless alumni"

December 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksCity Views

April 1977 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksThe Country Remembers

December 1979 By R.H.R.

Books

-

Books

BooksA DARTMOUTH NOTABLE

NOVEMBER 1931 -

Books

BooksHIGHWAY ENGINEERING.

July 1955 By CARL F. LONG -

Books

BooksA Higher Law

December 1978 By CHARLES T. DUNCAN '46 -

Books

BooksGIRAUDOUX, THREE FACES OF DESTINY.

JUNE 1969 By FRANK BROOKS -

Books

BooksTHAT GIRL OF PIERRE'S,

December 1948 By MARGARET BECK MCCALLUM -

Books

BooksTHE LOGIC OF LANGUAGE

November 1939 By Stearns Morse

R.H.R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksNotes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksMonticello to Montmartre

November 1976 By R.H.R.