LIEBLING ABROADBy A. J. Liebling '24Playboy Press, 1981. 672 pp.$17.95; paper, $12.95

For Abbott Joseph Liebling, a man of copious stomach and pinpoint eyes, digestion and observation were pretty much the same thing. He was a serious feeder and a serious writer, his appetite for a luncheon of rillettes, pate de lievre, jambon cm du pays,andouilles, tripes a la mode Caen, "five or six" beefsteaks, and souffle potatoes, topped off by a "remarkable pheasant" matched by his evocation of Easy Red Beach on D-Day, of girls with firm legs during the liberation of Paris, of a Gallic mustache in full foliage, of an American busboy nicknamed Mollie "Comrade Molotov, the Mayor of Broadway" a misfit with dreams who talked 600 Italian troops into surrendering to the 9th Division and was ultimately killed on a forester's track in western Tunisia in the spring of 1943. !

For some three decades The NewYorker's New Yorker, Liebling was master chronicler of Broadway lowlife, of the savants of the boxing ring, of the sins and pratfalls of the American press. In the beginning, he was kicked out of Dartmouth for too many chapel cuts (the class of 1924, doubly blessed, had another master chronicler, Norman Maclean), and soon thereafter under the threat of marrying a phantom mistress from Memphis Liebling flimflammed his father into sending him to Paris, where he commenced his education in the "essentials": food, wine, women. In the Latin Quarter, he took up with Angele, a "kind of utility infielder" in bed, who deemed him "passable" a compliment he treasured. ("Life in the Quarter," Liebling says in describing the affair of one of Angele's female friends, "was a romance that smelled of feet.")

In Liebling's universe, the sun rose and set on Paris, and Liebling on the way to Paris and Liebling in Paris is a marvelous feast.

Liebling Abroad is a collected reissue of four books published between 1943 and 1962, the year before his death. The RoadBack to Paris and Mollie & Other WarPieces serve up Liebling's personal vision of the war, a war that, for him, ended with the liberation of Paris. His journey to the center of the universe started on a Pan American clipper in 1939, traversed the campaign in North Africa, took a detour by way of a 42day Atlantic crossing on a Norwegian tanker, and then, in an exultant rush (with time off for meals), headed straight from the D-Day embarkation port of Weymouth to Paris. Liebling's war reporting was precisely controlled, seemingly effortless and moving:

The only residents of the farm [in Normandy] who seemed uncomfortable were a great, longbarreled sow and her litter of six shoats, who walked about uneasily, shaking their ears as if the concussions hurt them. At brief intervals, they would lie down in a circle, all their snouts pointing toward the center. Then they would get up again, perhaps because the earth quivering against their bellies frightened them. Puffs of black smoke dotted the sky under the first two waves of bombers; one plane came swirling down, on fire and trailing smoke, and crashed behind the second ridge of poplars. White parachutes flashed in the sun as the plane fell. A great cloud of slate-gray smoke rose behind the trees where it had gone down. Soon after that the flak puffs disappeared; the German gunners either had been killed or, as one artillerist suggested, had simply run out of ammunition. The succeeding waves of planes did their bombing unopposed. It was rather horrifying at that.

In Normandy Revisited Liebling, accompanied by a mildly crazed White Russian driver, journeys again 11 years later to Easy Red Beach, to Madame Hamel's farm near Vouilly, where he had made the acquaintance of some cows in 1944, to the memory of his dash to Paris with the French 2nd Armored Division. For all of Liebling's humor and self-satire, the journey is sentimental, wistful. So is his last book, Between Meals: An Appetite forParis, a work redolent of the "essentials," a paean to the good appetite. Proust ate a tea cookie, he says, and wrote a book. "In the light of what Proust wrote with so mild a stimulus, it is the world's loss that he did not have a heartier appetite. On a dozen Gardiners Island oysters, a bowl of clam chowder, a peck of steamers, some bay scallops, three sauteed soft-shelled crabs, a few ears of fresh-picked corn, a thin swordfish steak of generous area, a pair of lobsters, and a Long Island duck, he might have written a masterpiece."

In the end, Liebling records a conversation wherein a Paris friend tells him, long after the fact, of the death of Angele.

"What a pity she had to die. How well she was built!" the friend said. " 'She was passable,' I said. I could see that M. Peres thought me a trifle callous, but he did not know all that passable meant to me."

A. J. Liebling tasted life and wrote a book. Let us praise him.

D.A.D.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

December 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

December 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

December 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

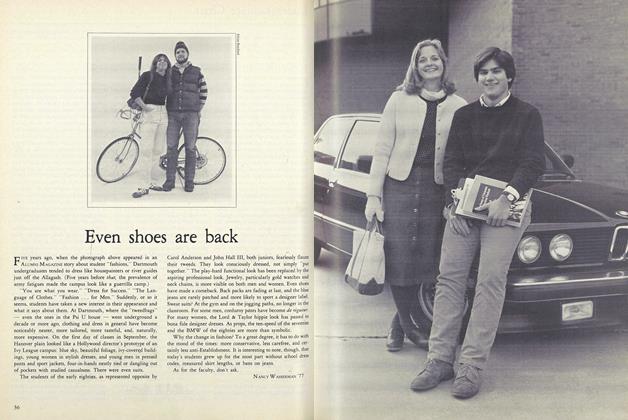

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

December 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Sports

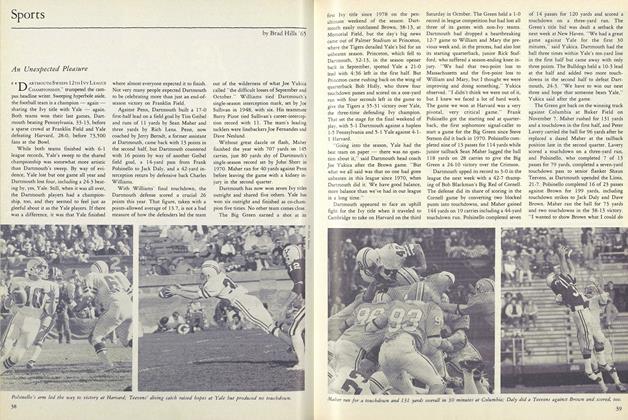

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65

Robert H. Ross '38

-

Books

BooksFRANK PEARCE STURM. HIS LIFE, LETTERS, AND COLLECTED WORK.

OCTOBER 1969 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksTHE FOUR SEASONS OF SUCCESS.

FEBRUARY 1973 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksProfligate Father, Square Son

April 1976 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFundaments

June 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksMountain Man

October 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksThe Alchemist

OCTOBER, 1908 By Robert H. Ross '38

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

MARCH 1971 -

Books

BooksTHE MOUNTAIN MEN.

MARCH 1964 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksTHE FAR AND THE DEEP.

MARCH 1968 By CAPT. L.S. SMITH JR., USN -

Books

BooksFURNITURE MARKETING.

MAY 1957 By CLYDE E. DANKERT -

Books

BooksTHE AESTHETICS OF THE RENAISSANCE LOVE SONNET: An Essay on the Art of the Sonnet in the Poetry of Louise Labe

MARCH 1963 By FRANK G. RYDER -

Books

BooksLIBRARY EXTENSION UNDER THE WPA AN APPRAISAL OF AN EXPERIMENT IN FEDERAL AID

October 1944 By Fred S. Harold