IT IS DIFFICULT enough to admit that I have been receiving the ALUMNI MAGAZINE for nearly 25 years; to say that it's nearly a quarter-century is harder. But it is, as lawyers say, a true fact. Whatever perhaps trite memories are inspired by the monthly return to Hanover, of the fall colors from the stadium while watching a football game (Clayton, Rowe, Miller, Calkins, Reich . . .), of bright sunlight sparkling on ice-covered campus, of the inspiration of a dedicated teacher (Finch, Cox, Laing . . .) or iconoclast (West) must be relegated to nostalgia, a thing of the past.

As this chronological sign of middle age became clear over the past few years, it was also becoming more and more clear to me as well that I had, and had always had, a problem with alcohol. I was an alcoholic. That is, of course, a shattering revelation, but fortunately I live in a community, Minneapolis, in which treatment is available. Not painless treatment, but effective treatment.

It was during that treatment that I related my Dartmouth experience and my drinking life. While I cannot and do not blame the College for anything that happened to me - nor is there any hard evidence to suggest that anything different would have happened to me had I gone to Haverford or Harvard - the journey back through my earlier years and the alcohol there presently led me to Hanover.

Further, the treatment program in which I was involved more than once found another Dartmouth man, a Dartmouth spouse, or references to my having attended a college renowned or notorious for the drinking atmosphere. These references were out of proportion to a random sample of the patients in treatment. So I have been prompted to express concern over the Dartmouth experience.

I arrived in Hanover in the fall of 1949, some two or three weeks after my 17th birthday. I would guess I was and am one of the younger members of my class. That in itself was to be a problem: it is interesting (although not productive) to wonder what I might have accomplished at Dartmouth had I been more mature. There was a cultural shock as I moved from a conservative New England preparatory school where drinking was prohibited to a conservative New England college where drinking was expected. If every dormitory man had one identical piece of personal furniture, it was a beer mug. The Jack O' Lantern's jokes, such as they were, referred to parties, dates, and drinking. Alcohol was a preoccupation, at least to an impressionable late teenager.

As I recall, there was also at that time some concern by the administration and the Trustees about the amount of drinking on campus. This concern had resulted in the adoption of drinking regulations: drinking permitted only during certain hours, at certain places, and, most surprisingly, only from eight-ounce glasses. Drinking was permitted only in designated areas of fraternity houses. Invitations were required for admission to fraternity parties. These regulations were attempts to control the parties; they were widely ignored, easily circumvented, and finally abandoned.

But the strong impression on an immature underclassman was that acceptance on campus depended upon the ability to imbibe ethyl alcohol. Even among the less impressionable it must have seemed that drinking was integral to the social process, especially at Dartmouth than at other similar colleges. After a the school was founded by a preacher with a Bible and 500 gallons of New England rum.

So, with that early introduction to ethyl alcohol, I continue; its acquaintance until, in the middle of 1974, I entered treating for alcoholism. From that experience I can say that if anything was missing at Dartmouth, it was hard facts about alcohol. '

In the educational process which is part of the treatment program, the alcoholic does learn that he has a disease, like diabetes, which can be diagnosed, treated, and controlled. It is a progressive disease which will be fatal if not treated. It is a feeling disease. There are no pills or injections.

Through the odyssey of self-discovery forced by my. own treatment, I did return to Dartmouth, to my own days there, my own impressions, and my own difficulties. Further, as I said. Dartmouth secured some notoriety in the program itself. Thus, while I certainly have no desire to embark on a messianic course to reform an institution which had been in existence for many years before I arrived, and will certainly survive me, I can simply ask this question: in view of the information now available concerning chemical dependency, should the College take, as one of its responsibilities, some education in this field?

I do not know whether things have changed. But this article was prompted by The Bulletin sent to the alumni in July 1975. That newsletter indicates that drinking is an integral part of Commencement and Reunions. The weekend in volves "Moe's for kegs"; "professors had students and their parents around for a drink and a snack"; "generous and spirited parents are good for the gin & tonic or chip-in for the keg"; important guests "were wined at the Kemeny home"; and the seniors hurriedly climbed the rocks into the Bema "where the beer was."

Admittedly, I read these words with a particular sensitivity. But this sensitivity is because of a problem which affects, I am certain, more of the Dartmouth family than is aware of it. My modest proposal would be that some awareness of the manifested, somehow, by the College.

Norman Carpenter is an attorney in Minneapolis.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

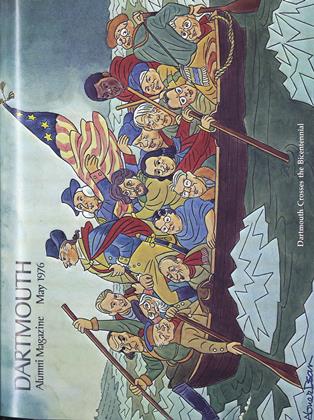

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

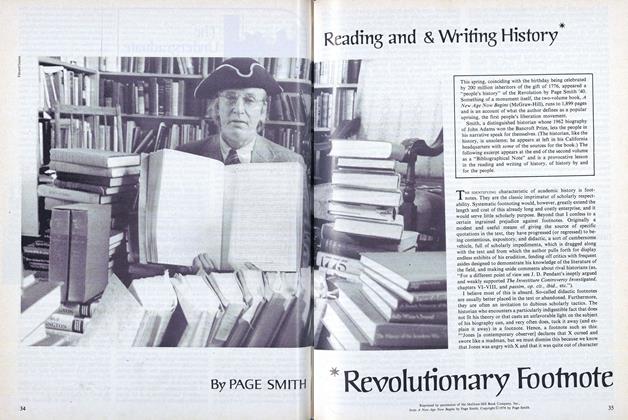

FeatureReading and Writing History and Revolutionary Footnote

May 1976 By PAGE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dartmouth Had Its Own State (Almost)

May 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleThe Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

May 1976 By Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1976 By WALTER C. DODGE, CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN

NORMAN R. CARPENTER '53

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1969 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

JUNE 1982 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

OCTOBER 1990 -

Class Notes

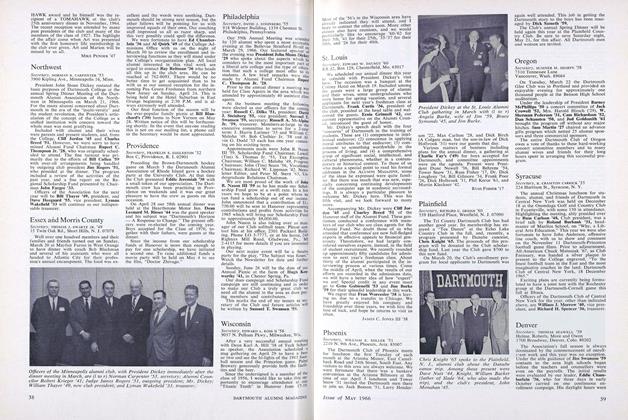

Class NotesNorthwest

MAY 1966 By NORMAN R. CARPENTER '53 -

Class Notes

Class NotesNorthwest

NOVEMBER 1967 By NORMAN R. CARPENTER '53 -

Class Notes

Class NotesMinneapolis

MAY 1968 By NORMAN R. CARPENTER '53