THE POLITICS OF INDIAN REMOVAL: CREEK GOVERNMENT AND SOCIETY IN CRISIS by Michael Green University of Nebraska Press, 1982. 237 pp., $18.95

That the Native American peoples of the eastern woodlands would ultimately be displaced westward to accommodate landhungry settlers of the seaboard colonies was apparent to many eighteenth-century observers. No sooner was the American Revolution over than the secretary of war despatched commissioners to treat with Indian nations that had remained loyal to the Crown, defining boundaries, establishing relations with the "General Government" and providing for the process of gradual civilization. In fact, the story of the treatment of the Indian peoples in the decades on either side of the turn of the century makes one of the sorrier chapters in our national history a chapter illuminated by a new book by a Dartmouth professor of history.

Michael Green's study of Creek society and government up until their removal to Indian Territory is a work of first importance, exemplifying recent recognition by historians that Native Americans offer a legitimate field for historical inquiry. It demonstrates how social and political change in Creek culture and society was a response to the pressures of white aggression The process that he outlines in the formation of the Creek Confederacy has parallels elsewhere in North America. Fiercely independent neighboring towns ie together and their national council evolved into a centralized government with strong internal leadership to face a common threat from violence. In many ways the Creek Confederacy is the bestdocumented example of this process.

Green's investigation stands on the solid footing of ethnography, notably the monographs of John R. Swan ton of the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of American Ethnology on Creek social and ceremonial life. Indeed, Swanton was among the first to employ ethnological concepts for interpreting early historical sources, an approach, now known as ethnohistory, that is shared by historians. Green goes overboard in clarifying the nature of the matrilineal clan and defining the avuncular relationship, missing the point that in such kinship systems as the Creek the father's kinsmen occupy a special relationship to sons and daughters of the mother's clan. Although the system functions to promote avoidance, special loyalties are owed those of the father's lineage who are indeed relatives. At a higher level the dual divisions of clans into "peace" and "war," "white" and "red" moieties separate functions and responsibilities but operate reciprocally. The American concept of "separation of powers" does not apply. Nor does "kitchen cabinet" seem appropriate to the "Beloved Men" who advise the headman. The discussion of the growth of the Confederacy is admirable, although much of it has to be inferred from inter-tribal wars. The intervillage Ball Game and the annual Busk at Green Corn were important integrating forces. External pressures are abundantly documented and comprise the body of the book. The historian's craft is evident in the analysis and interpretation of primary sources agency reports, council petitions, government documents, correspondence in manuscript and in print that expand exponentially from 1540 to 1836. The writing moves from the erosion of Creek autonomy before 1814 to the politicization of the Creek Agency and then the conflict between Creek Law and the Treaty of Indian Springs, 1818-25, which also features conflict between a stubborn Governor Troup of Georgia and President Adams. Although Congress abrogated that infamous treaty in following years, temporary federal intervention not only did not forestall driving the Creek from Georgia, but also presaged an unhappy interlude in Alabama and ultimate removal. The whole tortured process is a commentary on the failure of the Congress, the presidents, and the courts to exercise their responsibility toward a civilized people and on the powerlessness of the federal government to withstand the avarice of southern citizenry and ambitious governors voicing the doctrines of states' rights and eminent domain. Removal was a foregone conclusion from President Jefferson to President Jackson and a desirable consequence even to John Quincy Adams. Green is both a diligent scholar and a gifted writer: Many quotable passages illustrating the process of cultural and historical change could be presented, if space permitted. His publisher has served him well.

Most of William Fenton's 200 publicationshave dealt with aspects of Native Americanculture and history. He is emeritus distinguished professor of anthropology at the StateUniversity of New York at Albany.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni College Retrospective

May 1983 By Jean Dalury -

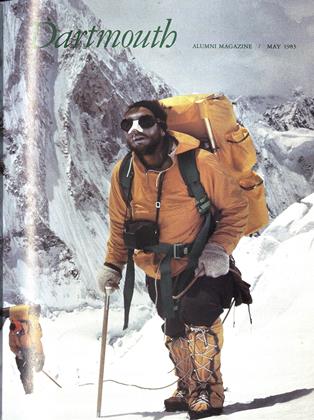

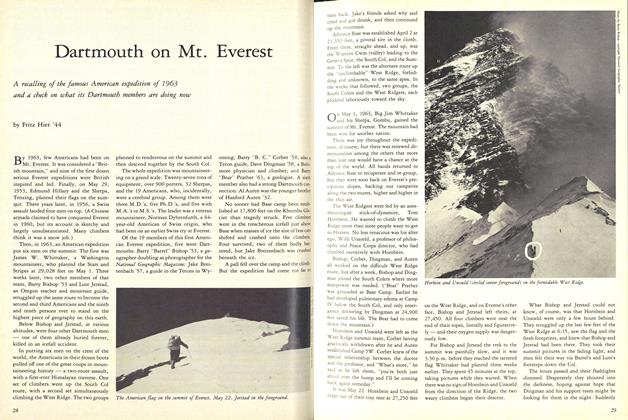

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mt. Everest

May 1983 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

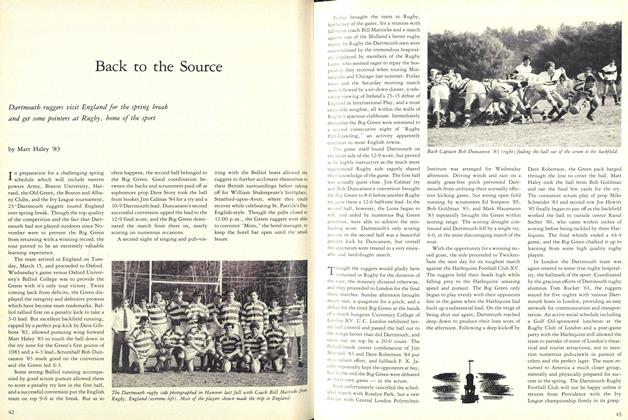

FeatureBack to the Source

May 1983 By Matt Haley '83 -

Cover Story

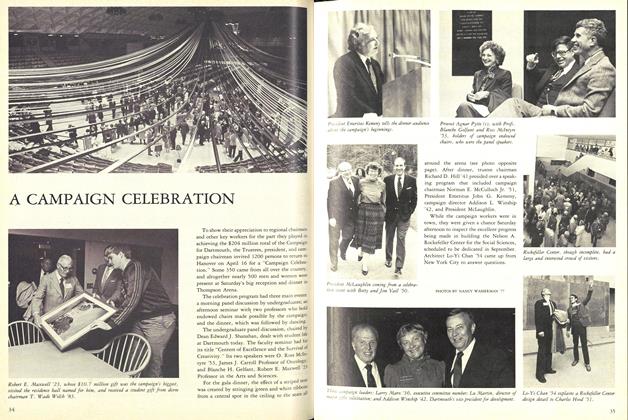

Cover StoryA CAMPAIGN CELEBRATION

May 1983 -

Sports

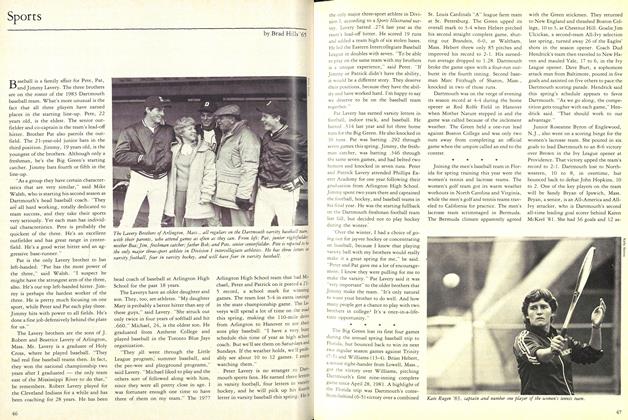

SportsSports

May 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

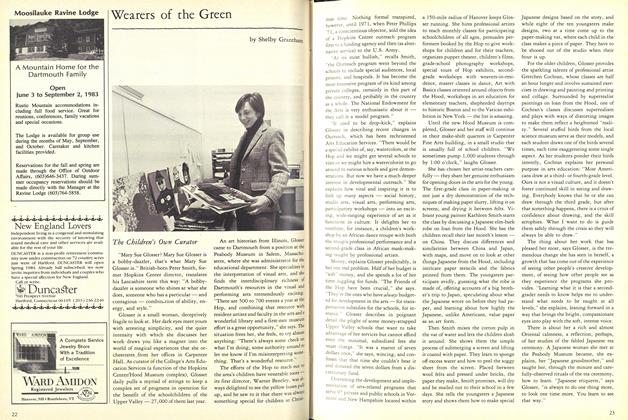

ArticleThe Children's Own Curator

May 1983 By Shelby Grantham

Books

-

Books

BooksAmerican Ski Annual, edited

January 1937 -

Books

BooksA MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH.

MAY 1971 By H. SHERIDAN BAKETEL JR. '20 -

Books

BooksFurther Mention

APRIL 1973 By J. H. -

Books

BooksMARRIAGE.

JUNE 1969 By LOUIS WOLF GOODMAN '64 -

Books

BooksCROKER THE TSAR MASTER OF MANHATTAN

June 1931 By W. A. Robinson -

Books

BooksTHE ROAD TO RENO.

June 1962 By W. R. WATERMAN