Rub it and, like the genie in the bottle,you can make music, art, and war

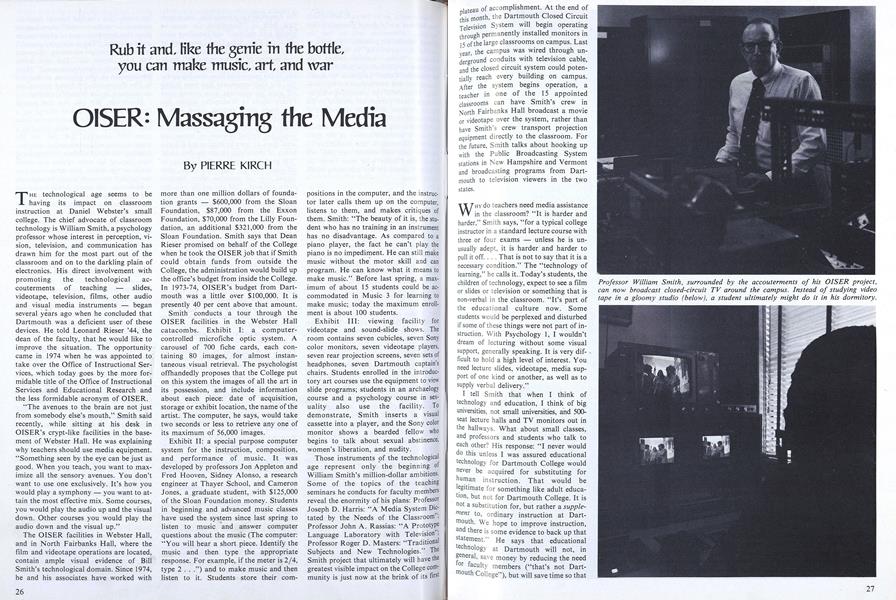

THE technological age seems to be having its impact on classroom instruction at Daniel Webster's small college. The chief advocate of classroom technology is William Smith, a psychology professor whose interest in perception, vision, television, and communication has drawn him for the most part out of the classroom and on to the darkling plain of electronics. His direct involvement with promoting the technological accouterments of teaching - slides, videotape, television, films, other audio and visual media instruments - began several years ago when he concluded that Dartmouth was a deficient user of these devices. He told Leonard Rieser '44, the dean of the faculty, that he would like to improve the situation. The opportunity came in 1974 when he was appointed to take over the Office of Instructional Services, which today goes by the more formidable title of the Office of Instructional Services and Educational Research and the less formidable acronym of OISER.

"The avenues to the brain are not just from somebody else's mouth," Smith said recently, while sitting at his desk in OISER's crypt-like facilities in the basement of Webster Hall. He was explaining why teachers should use media equipment. "Something seen by the eye can be just as good. When you teach, you want to maximize all the sensory avenues. You don't want to use one exclusively. It's how you would play a symphony - you want to attain the most effective mix. Some courses, you would play the audio up and the visual down. Other courses you would play the audio down and the visual up."

The OISER facilities in Webster Hall, and in North Fairbanks Hall, where the film and videotape operations are located, contain ample visual evidence of Bill Smith's technological domain. Since 1974, he and his associates have worked with more than one million dollars of foundation grants - $600,000 from the Sloan Foundation, $87,000 from the Exxon Foundation, $70,000 from the Lilly Foundation, an additional $321,000 from the Sloan Foundation. Smith says that Dean Rieser promised on behalf of the College when he took the OISER job that if Smith could obtain funds from outside the College, the administration would build up the office's budget from inside the College. In 1973-74, OISER's budget from Dartmouth was a little over $100,000. It is presently 40 per cent above that amount.

Smith conducts a tour through the OISER facilities in the Webster Hall catacombs. Exhibit I: a computer-controlled microfiche optic system. A carousel of 700 fiche cards, each containing 80 images, for almost instantaneous visual retrieval. The psychologist offhandedly proposes that the College put on this system the images of all the art in its possession, and include information about each piece: date of acquisition, storage or exhibit location, the name of the artist. The computer, he says, would take two seconds or less to retrieve any one of its maximum of 56,000 images.

Exhibit II: a special purpose computer system for the instruction, composition, and performance of music. It was developed by professors Jon Appleton and Fred Hooven, Sidney Alonso, a research engineer at Thayer School, and Cameron Jones, a graduate student, with $125,000 of the Sloan Foundation money. Students in beginning and advanced music classes have used the system since last spring to listen to music and answer computer questions about the music (The computer: "You will hear a short piece. Identify the music and then type the appropriate response. For example, if the meter is 2/4, type 2...") and to make music and then listen to it. Students store their compositions in the computer, and the instructor later calls them up on the computer, listens to them, and makes critiques of them. Smith: "The beauty of it is, the student who has no training in an instrument has no disadvantage. As compared to a piano player, the fact he can't play the piano is no impediment. He can still make music without the motor skill and can program. He can know what it means to make music." Before last spring, a maximum of about 15 students could be accommodated in Music 3 for learning to make music; today the maximum enrollment is about 100 students.

Exhibit III: viewing facility for videotape and sound-slide shows. The room contains seven cubicles, seven Sony color monitors, seven videotape players, seven rear projection screens, seven sets of headphones, seven Dartmouth captain's chairs. Students enrolled in the introductory art courses use the equipment to view slide programs; students in an archaelogy course and a psychology course in sexuality also use the facility. To demonstrate, Smith inserts a visual cassette into a player, and the Sony color monitor shows a bearded fellow who begins to talk about sexual abstinence, women's liberation, and nudity.

Those instruments of the technological age represent only the beginning of William Smith's million-dollar ambitions. Some of the topics of the teaching seminars he conducts for faculty members reveal the enormity of his plans: Professor Joseph D. Harris: "A Media System Dictated by the Needs of the Classroom : Professor John A. Rassias: "A Prototype Language Laboratory with Television Professor Roger D. Masters: "Traditional Subjects and New Technologies." The Smith project that ultimately will have the greatest visible impact on the College community is just now at the brink of its firs: plateau of accomplishment. At the end of this month, the Dartmouth Closed Circuit Television System will begin operating through permanently installed monitors in 15 of the large classrooms on campus. Last year, the campus was wired through underground conduits with television cable, and the closed circuit system could potentially reach every building on campus. After the system begins operation, a teacher in one of the 15 appointed classrooms can have Smith's crew in North Fairbanks Hall broadcast a movie or videotape over the system, rather than have Smith's crew transport projection equipment directly to the classroom. For the future, Smith talks about hooking up with the Public Broadcasting System stations in New Hampshire and Vermont and broadcasting programs from Dartmouth to television viewers in the two states.

WHY do teachers need media assistance in the classroom? "It is harder and harder," Smith says, "for a typical college instructor in a standard lecture course with three or four exams - unless he is unusually adept, it is harder and harder to pull it off.... That is not to say that it is a necessary condition." The "technology of learning," he calls it. Today's students, the children of technology, expect to see a film or slides or television or something that is non-verbal in the classroom. "It's part of the educational culture now. Some students would be perplexed and disturbed if some of these things were not part of instruction. With Psychology 1, I wouldn't dream of lecturing without some visual support, generally speaking. It is very difficult to hold a high level of interest. You need lecture slides, videotape, media support of one kind or another, as well as to supply verbal delivery."

I tell Smith that when I think of technology and education, I think of big universities, not small universities, and 500-seat lecture halls and TV monitors out in the hallways. What about small classes, and professors and students who talk to each other? His response: "I never would do this unless I was assured educational technology for Dartmouth College would never be acquired for substituting for human instruction. That would be legitimate for something like adult education, but not for Dartmouth College. It is not a substitution for, but rather a supplement to, ordinary instruction at Dartmouth. We hope to improve instruction, and there is some evidence to back up that statement. He says that educational technology at Dartmouth will not, in general, save money by reducing the need for faculty members ("that's not Dartmouth College"), but will save time so that teachers can be more available to students and can talk about more complicated material in greater detail. "If judiciously applied, it can improve the general educational process."

What about the human element: Can you duplicate the presence of a teacher? "Sure it is more authentic. If media were used all the time,' that would be impossible. That is why televised courses would not be and have not been successful. But the human element is patently not a necessary condition for the whole period of interaction." He dwells on the importance of appealing to the senses. People, he says, are moved not only by other people, but by books, by television, by movies, by art. "The response to non-human material is compelling unless it is used all the time. Which no one would do, of course. No avenue to the brain is intrinsically more important than the others. It depends on the quality of the material. Hell, I'm sure some media material is more compelling than real live teaching."

I wanted to talk with Dartmouth faculty members about classroom technology. But you begin to shoot daggers into the tenderloin with some teachers when you talk about their teaching habits. Some teachers have rapport. Others don't. I talked with John A. Rassias, a professor of Romance languages and literatures who has rapport. Rassias is one of the faculty members most involved in the development and use of instructional media at the College. At one of Smith's teaching seminars, he gave a talk entitled "A Prototype Language Laboratory with Television." At the moment, he is spending $58,000 of the Sloan money to develop his prototype language laboratory with television.

Rassias is a busy man, and his business is teaching languages and teaching other teachers how to teach languages. This month he holds his second five-day workshop at the College to teach representatives from other colleges such as Claremont, William and Mary, and the University of North Carolina how to teach languages his way. "I, by God, mean this: The country is in a bad way, language learning is becoming a disaster. We've got to reverse the trend," he says.

The way Rassias uses media is all tied up with the way Rassias teaches foreign languages, and the way Rassias teaches foreign languages is all tied up with Rassias' character, which needs some explaining He is an actor, on stage all day. His handshake is generous and firm and his voice resonates grandioso. He is unguarded in the high Continental style, and he is not afraid to answer his door with his pants down. His loosely-belted pants drag around because they are slower than he is. The sign on his door reads "Nose," which refers to his Cyrano de Bergerac nose. The sign on his desk reads "Monsieur LeCenseur." A woman speaks to him. "Bonjour, madame." He speaks a line in French, the next line in Spanish, the next line in French. He calls women "love," and kisses them grandly on both cheeks. A visitor interrupts a conversation between him and a clergyman. "I'm running late. Can you wait a few minutes? Just a minute. I'm going to flash a moon." He turns around, loosens his pants, and displays his boxer shorts. His boxer shorts have a round, dark patch sewed onto them. What's that?, "un cul de singe."

He had flashed the same kind of moon earlier that day in a French literature class. He had also engaged in hand-to-hand combat with some students, pursuing one student over three rows of chairs, while playing a sound track of an air raid and machine gun fire - this to recreate a scene from Tiger at the Gates, Jean Giraudoux's play about the fall of Troy. "War. Words won't do it." He quotes a line from the play, from an old mother who had seen her sons killed in war: "War is like un cul desinge." War is dirty. Its impact is visceral. "We know it to be, but you must feel hell, without any good.... How can students feel that? Most, thank God, don't know what war is. But how do you recreate war?" Once, while lecturing about Oedipus, he cut himself with a sharp knife and smeared the blood all over his clothes, all over his face. He showed the class what blood and pain look like. Another time he used hamburger meat, tomato sauce, and other ingredients to stink up the lecture hall and let his class know what it smelled like after Clytemnestra and Aegisthus hacked Agamemnon to death, to let his class know what death smells like. "The point," he says, "is to make teaching an art form. If teaching is viewed as an art form in itself, if all systems are working - the intellectual, the emotional, the imagination - it is an art form. Some literature, for instance, is not just for intellectual pleasure.... I do not think the intellectual does it alone. That comes from a deep-rooted conviction that it has to be demonstrated.... Teaching is a damn hard job. If it is well done, that does not mean it is just well done, but a successful enterprise. It's not just words." That's the way John Rassias talks. That's the way John Rassias teaches.

When Rassias talks about his Sloan grant project, he talks about coming as close as possible to having the language student "interact" with the medium. At present, his language instruction repertoire includes classroom instruction, using a book of conversational "scenarios," 30 minutes of finger-snap speed drills with a student drill instructor, and 30 minutes of work with language tapes in a language laboratory. His project, the prototype language laboratory with television, is meant to make up for deficiencies of the language laboratory. "It's a machine," he says of the standard language tape device. "You don't see a person sweating, perspiring, in front of you. There's no way to interact. There's no sense of urgency. You can play the tape for 24 hours and you'll have the same intonation, a timeless voice that drones and drones." Rassias is very interested in human beings, in "interaction." He emphasizes that a medium should not be used unless it is used as a "supplementary device" outside the classroom. It should not replace the teacher. The prototype language laboratory with television, he says, comes as close as possible to getting the student to "interact" with the medium. It draws the viewer out of the passive state. But its purpose is not to replace the teacher.

Here's how it works: The student first sees on videotape a four-minute scenario involving native speakers in a common situation such as dinner. Then Rassias comes on the screen as a drill instructor. There are also six chairs and five students on the set and Rassias starts pointing at students and firing questions in French. The entire drill session is filmed, sweat and all- It is important to Rassias that the sweat that accumulates on his face be visible on the videotape. Human beings sweat. When Rassias points at the empty chair during the drill session, the camera zooms in on Rassias' face, sweat and all, so that the viewing student is looking right into the image of Rassias' face. The student is to respond to the question as though he were sitting in the empty chair. The scenario is then repeated twice, once while the viewer follows on a script, once without sound or script but with the student himself recreating the dialogue. Finally, the student answers a ten-question quiz about the scenario. "It gives you outlets that you don't have in the classroom," he says of his use of television. "It's impossible in the classroom to get native speakers to act out a scenario for you.... I do not think any language lab can come near this thing. You've really been seized. It's not just a machine. There's sweat, perspiration, a gut reaction. It's saying, 'Here, see them stumbling, being human beings. Here, you are not alone.' "

As one English professor says, almost all teachers use some assistance in the classroom. The blackboard is the most basic visual prop. But the use of media in the classroom represents a great departure from the blackboard days of teaching. The question of whether to use media should not be one that faculty members answer without some thought. Media can enrich the educational process: Words can't convey the horror of war the way slides of maimed Vietnamese bodies can. But the effectiveness of the media use depends on the motivation of the teacher, and his creative abilities. An imaginative teacher, a teacher who has rapport in the classroom, will probably employ media in an imaginative way. The problems come when an unimaginative teacher uses media to enliven a dead lecture or replace it: Media without imagination would probably only reinforce the instructor's mediocrity.

Smith says that he thinks that within ten years some professors will work on preparing videotape cassettes to be distributed by publishing companies, rather than writing books. Yet he concedes that today the OISER equipment is not used enough. "I send memos to the faculty. It's surprising, a lot of faculty members don't know it exists." The heaviest users of OISER equipment are the departments of Art, Government, Drama, English, and German. "Many humanities professors think that media use is not necessary, that it demeans the subject matter. I, of course, disagree with them." Furthermore, there are some professors who seem to have a deep-seated resistance to the advancement of the technological age into the classroom. "I'm sure," says William Smith, "that some members of the faculty, even if you sit down with them, spend a day with them, and they agree with you about the media, about audio cassettes, but they wouldn't do it in the classroom because their work is so structurized, it would take hard work to change it."

Professor William Smith, surrounded by the accouterments of his OISER project,can now broadcast closed-circuit TV around the campus. Instead of studying videotape in a gloomy studio (below), a student ultimately might do it in his dormitory.

John Rassias emotes for the Dartmouth TVcamera. Working on a prototype languagelaboratory with television, he says that"Teaching is an art form... not just words."

Pierre Kirch '78 wrote about Transcendental Meditation in the February issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

FeatureNatural Energy Resource

May 1977 -

Feature

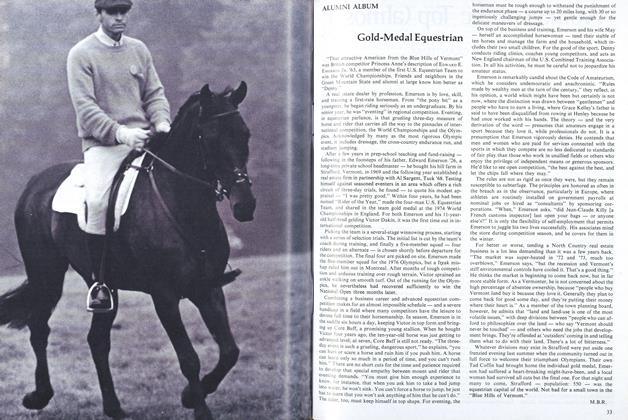

FeatureGold-Medal Equestrian

May 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleWar

May 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticlePaddler, Climber, 4-term Planner

May 1977 By D.M.N. -

Books

BooksNotes on justice finally done and old tales long in the telling.

May 1977 By R.H.R. '38

PIERRE KIRCH

Features

-

Feature

FeatureConserver of the Crafts

JANUARY 1972 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Faculty Policies

February 1954 By DONALD H. MORRISON '47h -

Feature

FeatureSpeaking of Books

FEBRUARY 1970 By FRANCIS BROWN '25 -

Feature

FeatureKappa Kappa Grandpa

MAY 1985 By Gabrielle Guise '85 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

Nov/Dec 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

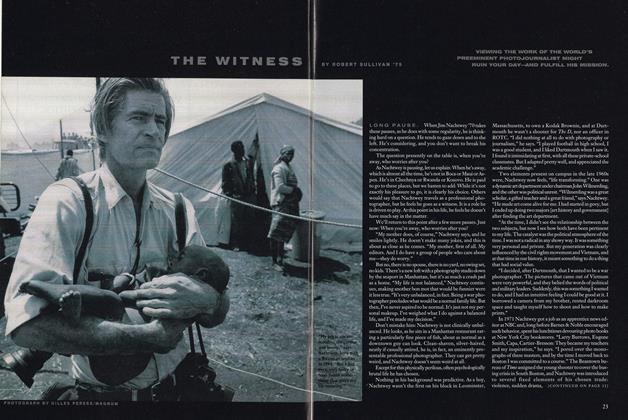

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Witness

JUNE 2000 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75