"THIS says the older woman proudly, "this is my daughter, the Dartmouth professor!" Assistant Professor of English Ellen Rose may find her mother's introductions embarrassing, but at least her own pride of accomplishment is not soured by parental disappointment. Not all of the Dartmouth professors who are women can say as much. Many had to swim against the tide of their parents' expectations. "Negative," says one professor baldly, describing her parents' reaction to her choice of career. "Mixed feelings," reports another, "they hoped I would be a suburban housewife." One set of parents withheld praise because husbands ought to lead and wives follow: "When I finished my master's degree, they didn't say anything, because my husband hadn't finished his yet. They were very pleased and proud when I got my Ph.D. and my job." "My father," writes one woman faculty member, "thought my decision to become a college professor was weird. While being a teacher was something my father approved of - 'something to fall back on' - being a college teacher was unnecessary."

They are not weird, these women. Ambitious, intelligent, hardworking, determined - but not weird. They are tired of being looked upon as "freaks in a carnival." "When I was a graduate student," grumbles Merrie Bergmann, assistant professor of philosophy, "I was an 'unusual' woman because I was good at what I was doing! #*&*!" Assistant Professor Mariann Jelinek (Tuck School) says with some impatience that while "women professors at Dartmouth" is a legitimate topic for the present, some day she will be interviewed not about being a woman, but about her latest theory of organization behavior. Her point is well taken.

Some of the women who are professors at Dartmouth aspired very early to a career in college teaching. Marysa Navarro, associate professor of history, says with a cheerful shrug that she always knew she "was going to do history and teach," and Assistant Professor Nina Allen (biology) reports that, according to her parents, she decided in the fourth grade to become a college professor. Jelinek says, "I have identified myself as a professional ever since I can remember: From the time I was, oh, maybe nine."

Others came to the decision as adults. Professor Emeritus of Biology Hannah Croasdale discovered in summer jobs that she "liked teaching and a college town." Some found their enjoyment of college led them to graduate school, which in turn led them to teaching - in college rather than in high school because, as Assistant Professor Carol Luplow (Romance languages and literatures) puts it, "there the intellectual level is higher and there is less of a discipline problem."

Assistant Professor Nancy Hayles (English) found working in industry as a chemist unsatisfying and decided literature and academia were more congenial to her temperament. Assistant Professor Lauren Levey (music) had a more pragmatic reason. "Composing," she points out, "is not self-supporting." Several, like Rose and Higgins, found the opportunities available to them as traditional wives and mothers inadequate intellectual stimulation. They enrolled in graduate school, kept going through the doctorate, and found themselves college professors as a result. Assistant Professor of Physics Marilyn Stockton, who originally saw herself doing industrial research, isn't sure yet why teaching appealed to her more.

Some had mothers who worked outside the home; most didn't. Some went to women's colleges, some to coeducational ones, some to men's institutions. Some were taught in college by women; others never saw a woman behind the lectern. Some have relatives in college teaching, most don't. Some are only children, others have brothers and sisters, both older and younger, and one is the youngest of seven.

And here is what everybody always wants to know about women professionals: Of the 23 (out of 48) women professors who agreed to be part of this article, 13 - more than half— are married. Seven are single, and three currently divorced. The spinster professor in tweed suit and tie seems to be a thing of the past - if, indeed, she ever really existed. I don't mean to suggest that marriage is easy yet for professional women. The job market is very tight these days, and very few husbands have followed wives to Hanover (I know of only three), with the result that many of the wedded women on the Dartmouth faculty live much of the year apart from their husbands. Though the commuting is a great hardship, to a woman they agree that the enrichment and support they derive from the marriages are worth it.

Fourteen of the 23 are childless. Their comments upon that situation range from "When parenthood comes it will complement and round out my life" to "I won't have children" and all the shades between.

One can prove almost anything about these professors with the information they have given me. I could depict them as dedicated scholars and teachers by quoting comments such as these: "It is vastly important to me to do publishable research - not so much to get it printed, but to do it. Publishing, though, is important from a professional standpoint." "Research and publication are activities which besides being satisfying in a very different way from teaching also improve one's teaching." Or - if I were so inclined - I might call their professional attitudes into question by quoting one who wishes there were "less pressure to publish rapidly." I could suggest they are naive by quoting one whose druthers include "higher pay, less academic and professional competition.''

I could show them as content: "I like my job the way it is." "I wouldn't change anything - I chose this job." Or dissatisfied: "I wish there were no team- teaching." "Decision-making should be less 'informal' and secret." Workhorses: "I wouldn't be retired." "I wish no one would make me retire at 63 or 65." Jealous of men: "Yes, I have wished I were male - in order to be able to exercise power and "I wish I had a wife to clean house, organize and take care of the children while I work!" Or happy with their womanhood: "I can say with absolute honesty that I have never wished I were male." "No. I would rather have the problems women have." "I like being a woman, because I am one, and because I find in my women friends more than in my male friends many things I value, such as humanity, generosity, sensitivity - things our society has worked very hard to make unmanly."

I can assert that au fond they are traditionally feminine: "Of course I like being a woman. I wouldn't change the experience of motherhood for anything in the world. I couldn't be anything else, so why not like what I am? It has given me my dauahter." Or unfemininely outspoken: "Bullshit! Of course I have wished I were male! And bullshit! Of course I like being a woman!" Or balanced and witty: "At times, I love being a woman; other times it is cumbersome, bothersome, difficult. Some of my most glorious experiences are connected with womanhood - childbirth, sex - but I also feel that being female has restricted in certain ways my potential for achievement. On the whole, I'm glad I'm a woman. I've always liked challenges."

In short, the group is composed of richly various individuals. All are women, all are Dartmouth professors - but beyond those common features, not much that is sociologically or psychologically interesting can be postulated as characteristic of women in this pocket of academe. I find that tremendously encouraging. It suggests to me that academic women are achieving both the security and the Lebensraum to be people, that they are fighting free of the pressures to be stereotypes and pseudo-men, freaks and tokens, and standardbearers.

But they are not altogether free yet. For there is one dark and common thread running through the thoughts of these women. It is an apprehensiveness about the permanence of the gains toward parity with academic men that all feel have been made in recent years. Perhaps Dartmouth has, as-Manager of Employment Ann Becker feels, come a long way, for an all-male institution, toward sexual equality. But then it had a long, long way to come. And it is poised now on the brink of one of the most telling steps it will be asked to take.

"THINGS are getting better at Dartmouth for academic women," writes the faculty's senior woman, Hannah Croasdale, from her winter quarters in Florida. "I was finally allowed to teach, and I got tenure just before I retired." Is her tone wry? Probably. Her history is a prototype of the treatment formerly accorded academic women. In the not-all-that-distant past, male-dominated institutions often made a practice, a possibly unconscious practice, of keeping useful women on the faculty until they reached retirement age without offering them the promotions enjoyed by male professors.

Croasdale, hired by Dartmouth as a research assistant (technician), came to the College in 1935 with a University of Pennsylvania Ph.D. in botany. Those were the days when a significant number of full professors had only M.A. degrees and a few only B.A.'s. Kept on in inappropriate departments (physiology and zoology) for 18 years, the by-then internationally famous algologist (specialist in algae) was finally granted faculty status in 1953.

She was made an instructor, in her own field - though not a regular instructor. Her cumbersome but (one assumes) usefully off-line title was "research associate with the rank of instructor." Six years later, she became "research associate with the rank of assistant professor." Another two years were required to bring her up to "research associate with the rank of associate professor." And finally, in 1964, after 29 years at the College, Croasdale became a real live associate professor, with tenure. She was 59 years old that year, and her publications, national and international, had become literally too numerous to list. She retired in 1971 as full professor of biology, though she is still professionally active. She got started teaching late, she says, and so she has been allowed to continue teaching beyond retirement.

The normal progression for a man of Croasdale's stamp is to be hired without experience as a promising assistant professor on a three-year contract, which is usually renewed for a second three years. At the end of that time his department and the College, in the light of their needs, evaluate him as teacher, scholar, and personality, with a view toward further promotion and tenure. He is either let go or promoted to associate professor with tenure. He will usually in another five or so years be promoted to full professor for a total of some 11 years from graduate student to full professor.

Here is- the way Croasdale herself sees her experience as a woman at Dartmouth: "Dartmouth kept me as a technician and would not let me teach for about 20 years when I asked to and could have. I was teaching at summer laboratories during that period. I did not teach, officially, at Dartmouth till I was in my late fifties or early sixties (I forget dates)."

A contemporary male colleague of Croasdale's recalls the situation this way: She took her Ph.D. in the time of the Great Depression when there were no jobs, particularly for women. At the nudging of his daughter, longtime friend of Hannah's Professor C. C. Stewart of the Medical School took her on as technician, to help with his research on muscle physiology in frogs - she an algologist! Later the job of technician to the Zoology Department opened up (as it had with some regularity) and the department offered it to her. She became the first, and for some years the only woman on the staff in Silsby - and this was resented by some of the elder professors, as an abstract proposition, you understand. Younger people came along, and much later she began to teach, first in labs, then with her own courses. Before that, the "young Turks" began to agitate for faculty status for her - which came by steps.... If my memory is right, she didn't get a chance to run her very popular course in algology - her specialty and a very basic subject in biology - until the zoologists and botanists were put together again as a biology department.

He goes on to speak of Croasdale as a "spectacular" teacher - "Dynamic. Devoted. Totally competent in her specialty. She was very popular and demanding and effective." His conclusion is a poignant illustration of the way our society so often squanders its gifted women: "We all knew she was vastly overtrained for the job as technician in zoology, but there was next to no communication between the zoology and botany departments in those days. I doubt if the thought had ever been entertained to transfer her to botany where she could have had the kind of career she deserved."

Croasdale came to Dartmouth first, but she was not the first woman to hold professorial rank on the College faculty. Nadezhda Koroton, assistant professor of Russian language and literature, was the first. Though the statistics are not as outrageous in her case as in that of Croasdale, the pattern is the same. She came to Hanover in 1950 to teach Russian, hired as an "associate" in the Russian Civilization Department. After five years of teaching - that is, at the point in her career when most male faculty are being considered for an associate professorship with tenure, she was raised to the first rung of the professorial ladder. And there she remained, untenured, for the next 11 years until she retired with the curious title "assistant professor emeritus."

Neither as renowned nor, apparently, as determined as Croasdale, Koroton was nevertheless as qualified academically as four of the ten male full professors who retired with her in 1966 and better qualified than one. "One wonders," I said to Chairman of the Russian Department Richard Sheldon, "why such a person was kept so long at the assistant professor level." "No, one doesn't wonder," Sheldon replied with refreshing candor. "She was a woman. And I have the sense that there was at that time a sort of policy that the Dartmouth faculty was all male."

From newspaper accounts of her single promotion, which occurred the same year in which she received her U.S. citizenship, it appears that Koroton regarded the latter as the more important. A Russian refugee with a tragic family history of persecution and flight, Koroton was - and still is - touchingly grateful just to be able to sleep at night without fear of arrest. By telephone from her home in Michigan, she sent back her "deep love" to Dartmouth, after recalling her appointment as the College's first woman professor with these words: "I never expected the professorship. I never thought of it. First, because I am a lady, and also because I was such a poor newcomer to this country. It was a big honor." From her point of view, it was, indeed, a big honor; from Dartmouth's point of view, it was a great, a significant departure from tradition and a paltry honor.

These are two of Dartmouth's family skeletons. There are others. Marysa Navarro feels strongly the professional insult of her first appointment at Dartmouth. She was teaching as associate professor with tenure at a New Jersey college (admittedly less prestigious than Dartmouth) when her divorce made it necessary to leave the New York City area. Dartmouth, she says, offered her an assistant professorship with the warning that after four years, either she went up - or out. She went up - "Just like a man, onscheduleas she says - and can now speak without bitterness of this original offer, one which she feels no self-respecting college would have made to a man in her position, and which no man in her position would have had to accept for lack of others.

And as late as 1974, according to my data, women faculty applicants with children were still being asked personal questions they feel were not asked of male applicants, questions such as this one, recalled from a Dartmouth interview: "What would you do if you awoke one morning you were scheduled to teach and discovered that one of your children had measles?" (To understand the inappropriateness of such questions, one has only to imagine a male candidate being put on the spot with something culturally analogous, such as, "What would you do if you awoke one morning you were scheduled to teach and discovered that your wife had appendicitis?")

BUT Croasdale and Navarro have tenure, Koroton is not at all unhappy with Dartmouth, and the applicants with children were hired. The skeletons are being properly buried, and the closets aired. Last year 17 out of the 38 new faculty members appointed in Arts and Sciences, at Thayer, and at Tuck were women: almost 45 percent. Discrimination against women is passing - forever, one hopes.

Most of the recently hired women professors feel, on a personal level at least, that, as Croasdale says, things are getting better at Dartmouth. Assistant Professor Peggy Hock (psychology) says she has encountered "very little" discrimination. "Never," Assistant Professor Carolyn Ross (drama) says firmly. "I was treated very fairly by Dartmouth College." Stockton is "not aware of strong differences" between the way she is treated and the way her male colleagues are treated. "For the most part, no discrimination," says Jelinek. Hayles reports that the Dartmouth English Department was "absolutely super and didn't ask me any questions of a discriminatory nature. They were extremely tactful." Luplow penned a strong, clear "No" in answer to the question about personal experience of discrimination.

But when you ask these women to move beyond their personal experience, they hesitate. They must consider what they have heard about other women in other departments and consider current data being published about the status of women. The data, appearing in respectable publications such as The Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, suggests that both minorities and women are at present standing still in their progress toward parity with white males, and they may, in fact, be losing ground. The most universally acceptable proof of discrimination - wage and salary inequities - is available, and discouraging.

"My personal sense is that academia is slowly becoming more congenial to women," Hayles says, and then adds, "I'm confused by recent MLA [Modern Language Association] investigations which indicate that sexism is still rampant in English and language departments. I'm obliged to accept the data, but it does not correspond to my personal experience." "Are things getting better, worse, or remaining constant for academic women? I just don't know," says Rose, as does Levey: "I don't know; all three maybe. It's confusing right now."

Others articulate more precisely the source of their uncertainty. "I think things are getting better, especially in hiring," says one assistant professor, "but granting of tenure seems to be still strongly ruled by tokenism, and the power to grant tenure and make major decisions is still male." Sara Castro-Klaren, associate professor of Romance languages and literatures, says, "I honestly don't know. I see more women with jobs, at meetings, with publications, but I don't see more women at the top, who are truly independent (no sugar daddy), much less real feminists." Another member of Castro-Klaren's department, Assistant Professor Marianne Gottfried, echoes her colleague: "Affirmative action forces colleges to hire women, but there is no support system for women once they get there: thus many have difficulties and end up being fired after their first contract expires. Thus, although it's easier to find a job, it's harder to keep it."

The distinction between hiring and promotion is a crucial one. The few unreservedly optimistic responses I received were based on experiences of hiring practices only. Hock's is an example: "Things are getting better," she says. "Women are being given a fair chance, perhaps a better than even chance. My opinion results from my experiences on departmental search committees and my experience with departmental admissions policies for graduate students. In addition, I hear of the recruiting policies of departments in which my friends (many are female) teach."

Equally unambiguous in another vein is the response which came from Assistant Professor Marlene Fried (philosophy), whose paper on the current status of academic women is in process of publication: "There has been no change. Essentially affirmative action has not helped. This perception is based on research I have done."

Part of the difficulty in assessing the situation, as Levey points out, is that "the problems are much more subtle than they were five years ago." The subtle problems right now, as these women see them, are problems of recognition, acceptance, validation - authority. Colleagues often refuse to grant them authority as colleagues, and students often refuse to grant them authority as teachers and scholars. "The direct confrontations can be rather easily dealt with," writes one assistant professor. "It's the chronic avoidance, professional isolation, mysterious lack of collegiality that drain me. I think, really, that in most cases it's largely that male colleagues are afraid I'll be perceived as a threat to their marriages or something, more than the obvious forms of sexism. So they don't work with me closely." Stockton agrees that this inability of male colleagues to see beyond her sexual identity to her identity as their co-worker is a difficulty: "At conferences, being a woman makes a difference: there is a decided reluctance to go to dinner with me unless a large group is included - for obvious reasons. Most of them are married and don't want to be seen with another woman." Whatever the reasons are, professional isolation is felt by many of these women, for whom Fried speaks when she says tersely, "It is a matter of being taken seriously."

The problem also occurs in the classroom. A student of one of Dartmouth's best-qualified women is reported to have fumed and chafed under her tutelage until, unable to contain his amazing indignation, he finally shouted at her, "I just can't stand being taught by a woman!" That's an extreme, of course. Most instances of student contempt for women are less blatant. Sherry Frese, a John Wesley Young research instructor in mathematics (with the rank of assistant professor), recounts how a young man asked on the first day of class to transfer out of her section into that of a male professor, alleging lamely that he knew he and she "just wouldn't get along." Frese also recalls that another of her students absolutely refused to take her word that an exam question was acceptable and had to be hauled down to the office of a male professor, from whom he accepted, the same answer instantly and without demur. No wonder she says, with a puzzled frown, "I feel I lack authority."

She is not alone. It is not "just my perception," as she offers. "Since authority in this society is primarily white and male," explains Fried, "students like everyone else have difficulty when women assume positions which are primarily occupied by men. This often takes the form of students' asking for things which they would be afraid to ask of male professors, such as extensions, etc." Rose also cites such experiences: "When I've team-taught with a man (always a senior member of the department), I have felt that the students look upon me as very much teacher's aide rather than teacher. How much of that is because I'm a junior member, how much because I'm a woman, I don't know. Interestingly, when Brenda Silver and I team-taught an upper level course, the students (male and female) called us Brenda and Ellen, although we had not invited them to do so. Nobody calls Peter Bien Peter."

On the other hand, several women, including some of those quoted above, agree that their failure to get the "automatic and immediate deference" accorded male professors is on occasion advantageous. Perhaps, they muse, students are "a little more comfortable with you; they can talk to you." Perhaps "they fear you less, and give you more feedback. Maybe." In the end, though, the conclusion is that the disadvantages outweigh the advantages.

Interestingly, both Berger and Navarro have the feeling that women (in general) offer an advantage not (in general) offered by male professors. Navarro has "the sense that we women are less pompous than the men here are about serious things." Berger seems to be saying something similar when she speaks of the teaching tradition she finds oppressively in vogue at Dartmouth - the big, dramatic lecturing style, which she feels men of this culture are more apt to adopt than are generally quieter women scholars. It is for her a suspect "flexing of the intellectual muscles."

Perhaps women do (by and large) refuse to play by the rules of intellectual oneupsmanship that do (by and large) grace the male faculty-student relationship. If so, however, their doing so may well constitute a waiver of the right to that "automatic and immediate deference" that they miss in the classroom and to the collegiality that they miss in the department meeting. Ann Becker feels strongly that women's failure to play by the established rules is the source of their greatest difficulties in breaking into the hierarchy. Becker insists that women need to learn the ropes of what is called "the old boy network." She urges that women seek established male mentors to run interference for them and guide and prod them through the mazes of career.

Not unreasonably, however, many women find the demand that they play by the established rules - rules created with only men in mind - tantamount to a demand that they give up their womanhood in a doomed attempt to be just like men. They find in the notion of cultivating a male mentor a situation distastefully akin to the sugar-daddy/gold-digger relationship. They want to make it "on their own." Is this naivete or healthy idealism? The old, vexed question rears its hoary head: Can you change the system from outside? Or must you first infiltrate and beat it at its own game?

The next few years will tell part of this tale at Dartmouth, for in the next few years begins the real test of the College's committment to the principle of equality of opportunity for women. It has yet to commit itself fully to the principle with regard to students; many of the women with whom I spoke are apprehensive about the situation with regard to the faculty. The burning question is advancement, for without promotion to the elect and decision-making ranks of associate and full professors with tenure, faculty coeducation is a sham.

Jelinek alone is certain about her chances for tenure. None of the other women to whom I spoke can match her supreme confidence. (Nor can many untenured male faculty for that matter - not in a desperately overcrowded market.) Asked what she would do if she failed to get tenure at Dartmouth, Jelinek snapped up straight in her chair and said, "Well! First, I'll be very surprised!" She went on to explain: "I don't anticipate difficulty. My teaching is good and getting better, I'm interested in research, and my publication record is good. I mean to be superb!"

But Jelinek points out that her chances are better for her having changed fields. When Jelinek discovered that as a new Ph.D. in English she could not get even an interview in the overcrowded English market - she was married, they said, and didn't have to support a family - she turned right around and took another doctorate, this one from Harvard, in business "The academic ivory tower has affinities to the Middle Ages," she says acidly, " English is a dinosaurJelinek attributes the egalitarianism she encounters in business to the fact that it "is a lot closer to cultural currents than is, for instance, English. Business can't afford to hole up in an ivory tower."

That's the way its one woman faculty member sees the tenure question at the Tuck School. There are no women a; Thayer, and things in Arts and Sciences don't look good by several accounts. Affirmative Action Officer Margaret Bonz expresses concern over noises now being made to her by high-level administrators. "They have said to me that many of the women we hired in the early seventies at the time of coeducation were snatched up quickly and carelessly and that they are weak as scholars and teachers." Bonz sees this pre-tenure-time muttering as ominous.

Assistant Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Nancy Vickers reports "hearing from certain tenured faculty members comments to the effect that they don't think women can cut it. that they don't like the idea of tenuring women." Luplow says, "I still hear women at Dartmouth (both students and employees) talk of prejudicial attitudes which have been expressed against them, and I hear men as well admit that they know of male colleagues who hold discriminatory attitudes and try to act upon them." Male as well as female professors tell me that some departments at Dartmouth - economics and psychology in particular - are reputed still to be virulently sexist.

The numbers are these: 326 total faculty/55 of them women; 171 total tenured faculty/6 of them women; two women scheduled for tenure review this year; five scheduled for review next year: two more for the year following.

Will the tenure barrier go down? And if it does, will it go down wisely and gracefully - or over dead bodies? "I'm skeptical," said Navarro, with an anxious frown. Then she smiled suddenly and added with engaging sincerity, "But I'd love to be proved wrong!"

If she is wrong, Dartmouth will meet its affirmative action goal of 20-25 tenured women faculty by 1982. Eighteen by 1982 would represent 33 per cent promotion to tenure, which proportion is the one currently operative among male faculty at Dartmouth. In either case, a vital start will have been made. Thirty-three per cent of 16.9 percent of the total faculty isn't much, but it is a real, convincing beginning.

Professor Emeritus Hannah Croasdale:"Things are getting better at Dartmouth."

In committee with colleagues is Marysa Navarro (center): "I'd love to be proved wrong!"

Assistant Professor Marianne Gottfried:"There is a kind of excitement about making breakthroughs as a woman and abouteffecting profound changes in our society."

The Tuck Schools Assistant Professor Mariann Jelinek: "I mean to be superb!"

Shelby Grantham is an assistant editor ofthe ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOISER: Massaging the Media

May 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureNatural Energy Resource

May 1977 -

Feature

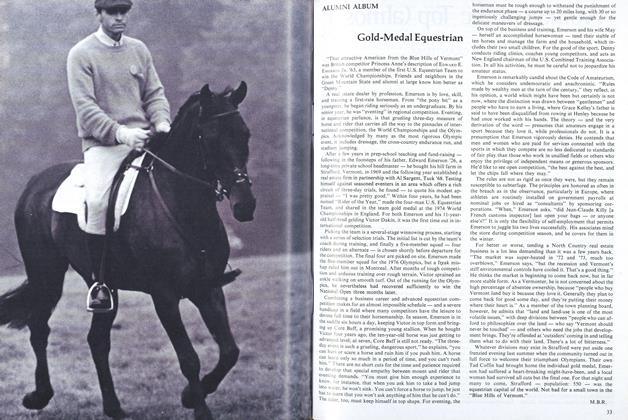

FeatureGold-Medal Equestrian

May 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleWar

May 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticlePaddler, Climber, 4-term Planner

May 1977 By D.M.N. -

Books

BooksNotes on justice finally done and old tales long in the telling.

May 1977 By R.H.R. '38

SHELBY GRANTHAM

-

Feature

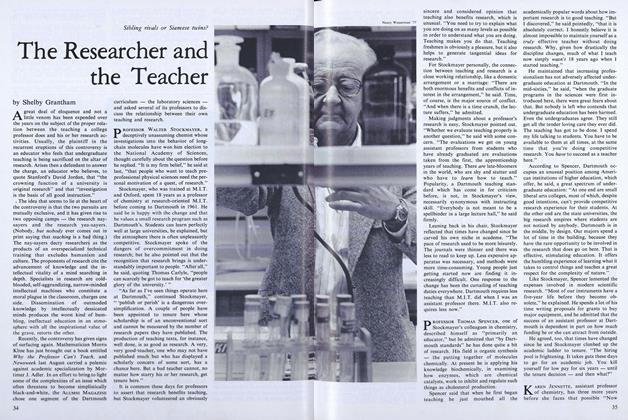

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureNine to Midnight (or two if hot)

March 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureA winter of discontent, a day of perceiving differences

April 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

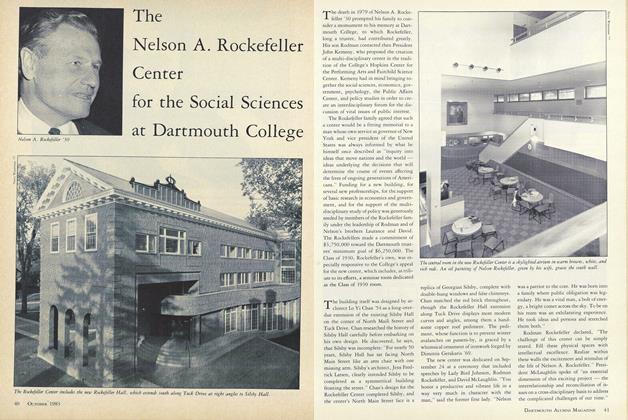

FeatureThe Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for the Social Sciences at Dartmouth College

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover Story"GALLANT SERVICE"

May/June 2013 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOCCOM’S DIARY

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureThe 1958 Commencement

July 1958 By C.E.W. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO THROW A REALLY BIG SHOW

Sept/Oct 2001 By ERIC MARTIN '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Responsibilities of Management

March 1956 By J. IRWIN MILLER -

Feature

FeatureEducation's Marshall Plan

JULY 1967 By ROBERT H. WINTERS, LL.D.