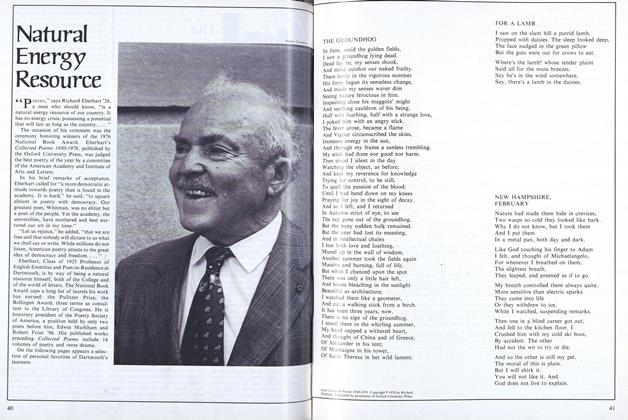

Etched into memory, the scenario is readily recalled by thousands of aging Dartmouth alumni. The time: Saturday, November 16, 1940, late afternoon. The place: Memorial Field. The score: Dartmouth 3, Cornell 0. Fourth quarter; the clock shows less than ten seconds to play in the game; the ball is on the Dartmouth five-yard line. A Cornell fourth- down pass into the end zone has just been batted down by quarterback Don Norton. The ball must now go over to the Dartmouth team which has only to run out the remaining few seconds on the clock. Feet stomp, voices roar, hats sail into the air: Dartmouth has upset number-one-ranked Cornell!

But no. Inexplicably, with no sign of a penalty having been called, referee Red Friesell gives the ball to Cornell again. Incredibly, the final seconds of the game are theirs, not ours. Stunned silence, disbelief, some howls of protest. A short Cornell pass - touchdown! Successful conversion. Final score: Cornell 7, Dartmouth 3.

By the following Monday, having the game films, Friesell concedes in a telegram to Captain Lou Young that Cornell had indeed been awarded a fifth down, and shortly thereafter Cornell officially forfeits the game to Dartmouth. It goes into the record books as a 3-0 Dartmouth victory and into history as the famous Fifth Down Game, one of the most bizarre ever played.

But the memory lingers on. And now, almost 40 years later, the event will be recreated in a book being written by Robert F. Porter. A University of North Carolina alumnus with no previous Dartmouth connections. Porter is a sports historian and lecturer whose interest in the fifth-down game dates back to an evening in late 1940 when "as a kid," he recalls, he saw a Movietone newsreel film of the game. "It stuck with me," he says, and finally in 1975 he found he could no longer deny the urge to write the book which had been germinating for 35 years.

His undertaking is ambitious. He is employing the same form, he says, as that used by Thornton Wilder in the famous Bridge of SanLuis Rey. Wilder's novel opens with the climactic event, the collapse of a bridge carrying five people to their deaths, and then traces the strange concatenation of forces and even's which had inexorably brought five strangers to their shared fate at one precise moment of time. "By the same token," Porter writes, "I wish to show all the factors that brought members of both teams to play in this historic football game." Though he stresses historical accuracy if Porter can carry off his initial conception he may perhaps end up with more of the stuff of a historical novel than of history itself.

Porter's research has been nothing if not thorough. He has traced down every surviving member of both teams, every game official every coach, and has either taped interviews with each or has corresponded at length with those whom he could not personally visit. He estimates that he has talked with well over 50 of the participants. A few gaps were inevitable: some members of both teams, including Charles ("Stubbie") Pearson '42 and Remsen Crego '43, had been killed in service during the War, and Friesell had died before Porter's research was begun. By searching out and interviewing surviving relatives, however. Porter managed not only to fill some gaps but also to unearth scrap-books and other first-hand memorabilia which might otherwise have remained untapped.

One of the most gratifying pieces of serendipity for Porter came after he appealed for help last summer to Herb Marx, newsletter editor for the Class of '43. Did Marx know anything, Porter inquired, about a specific member of '43 who had played in the game? Marx didn't, not personally anyway; but via Clanging Bells, the '43 newsletter, Marx broadcast Porter's request for help and, while he was about it, solicited any and all recollections from classmates regarding the fateful game. The response was overwhelming Former team members in the class, spectators, athletic heelers, and just plain nostalgists: the Class of '43 replied in droves, some with a rueful sentence or two ("The shame of my life is that I chose that weekend to go to Philadelphia!"), others analytically and at length. Marx printed the replies in his December 1976 issue and then forwarded them to Porter for his research files.

"One of those times in life when you remember exactly where you were," wrote one '43 respondent who, being a DCAC heeler for the game, found himself standing next to Coach Red Blaik. Normally a reserved man, even Blaik lost his cool that day: "When the Cornell team lined up for the fifth time, the coolness departed and I heard the colonel swear, for the first time. It was loud and clear, and totally understood." All the writers testify to the wildly fluctuating emotions of those last few moments. First the exhilaration: "After the fourth down I was so certain of our win I sailed a pretty good cap into oblivion"; or "Never before or since have I been so emotionally caught up as a spectator - totally drained to the point where I was fighting to hold my lunch down and having little consciousness of my environment." Then the despair: "It was snowing lightly - light fading and everyone was jubilant. . . . Then came the final play, ... a hush fell over the Dartmouth crowd like a pall and people left the stadium in silence." And finally the question, the obvious but nagging question: "The Cornell touchdown, placement and despair - the half-uttered words of disbelief. Could the officials have been wrong? Possibly?"

Among the responses was even one from a widow of a member of' 43 who reported meeting Friesell 15 years after the event and finding him "a delightful person" who was "not bowed down with remorse for his call of a fifth down." A class member summed up another aspect of the aftermath: "It was not difficult in the years that followed to run across Cornellians around the world who still felt that injustice had been done. And when I would point out that their own university had formally forfeited the game, I would get the occasional rejoinder, 'You've got to remember that our president went to Dartmouth.' "

So welcome to the Dartmouth circle, Robert Porter. We trust you didn't find that massive response from the Class of '43 too dismaying, They're a fine class no doubt, but they aren't the only ones with long memories. We all have them, and by and large we're a gregarious, garrulous bunch, Mr. Porter. Perhaps your experience with the Class of '43 has already suggested to you a fundamental rule of survival: never, never, Mr. Porter, ask a Dartmouth graduate to recall an event of his undergraduate years for you - not, that is, unless you are prepared to learn a great deal more about the subject than you want to know.

In fact, have you heard the one about the Twelfth Man Game? Let's see now: it was down in Prinnceton in '35, I believe - or was it '34? Anyway, it was snowing, a heavy, wet snow, and Dartmouth was putting up a really magnificent goal-line defence. The two teams were lined up, the Princeton center was over the ball, when suddenly from out of the stands there came....

Good luck with the book, Mr. Porter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

FeatureOISER: Massaging the Media

May 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureNatural Energy Resource

May 1977 -

Feature

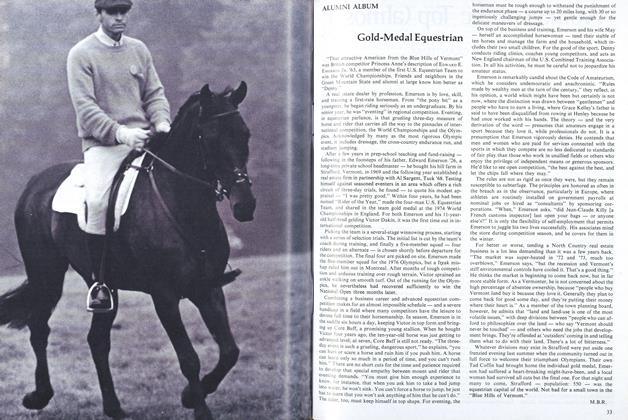

FeatureGold-Medal Equestrian

May 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

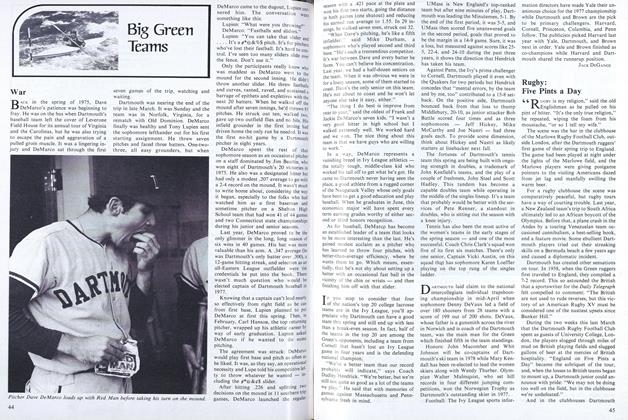

ArticleWar

May 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticlePaddler, Climber, 4-term Planner

May 1977 By D.M.N.

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE "WHY" OF MAN'S EXPERIENCE,

January 1951 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Books

BooksA SHORT HISTORY OF LITERARY CRITICISM.

FEBRUARY 1964 By HARRY T. SCHULTZ '37 -

Books

BooksANY OLD WAY YOU CHOOSE IT: Rock and Other Pop Music, 1967-1973

March 1974 By J. MICHAEL STUART '71 -

Books

BooksLAUGHTER AND TEARS.

FEBRUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksPIERRE-SIMON BALLANCHE:

August 1946 By MARIE-LOUISE MICHAUD HALL -

Books

BooksHow Much Freedom?

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith