Strong drink the old New England way

THIS is written for people who like to go to folk museums, who like to collect antiques, who like to renovate old houses, and who like to drink. There are abundant records of how our New England ancestors quenched their thirst, much of it in the form of old grandfather's tales and some of it accurate enough so that if you really want to collect an old-fashioned beverage museum for yourself, it is both satisfying and fun.

Taste and smell are difficult to describe by the written or spoken word. To understand what the colonial Americans meant when they talked of small beer, applejack, or metheglin, it is not enough to describe what the beverages were and why they developed; you must actually drink, taste, and smell. That creates a problem. Few of us live in woods where we can chop down a 40-foot-tall black birch tree whenever we want to make five gallons of birch beer, and even fewer have the readily available free labor of large families with many children brought up in a culture where they are expected to work for one another day and night. Yet to make five gallons of birch beer requires that every leaf bud be gathered from the 40-foot tree as flavoring for the finished drink as it was made in the 18th century. To reconcile the necessity of tasting with the impracticality of trying to recreate every old technique and method, I have carried on the investigation in double fashion. Once having successfully mastered the art of any particular drink, I have used the end product as a norm against which to test more practical recipes for our modern living. Both the old and the new versions appear here.

My aim is to describe and make real the history of the technology of wine- and beer-making in the New England frontier. This aim differs markedly from the many volumes devoted to making homefermented drinks. In general, they try to create equivalents to accepted types and tastes. Books and magazines abound to tell the enthusiast how to make beers and ales; yeasts are readily available to simulate clarets, burgundies, madeiras or champagnes; and success is gauged by how indistinguishable the home product is from the "genuine." This is very far from the idea of recreating an ancient taste. In terms of looks, a lovingly brewed lager, fermented with imported yeasts and clarified to a sparkling transparency, rivals in the eyes of the hobbyist the finest on today's market, but it is a far cry from the murky, muddy-looking porter that was so highly praised by the first president of the United States....

One further motivation stimulated these explorations. As our modern society has become more and more complicated, as population continues to increase and our cities become more crowded, a greater and greater number of young people are looking for a simpler, more unhurried, and closer-to-nature way of life. But many who know little about living in the fields and the forests discover their attempts to escape unbearably hard and finally do not make it, not for a lack of will but for a lack of a way. Those who know how to find gourmet salads and vegetables on the roadsides, who can guide the uninitiated to succulent mushrooms on the forest floor, or who know how to provide excellent wines and thirst-satisfying beers from the woods and farmlands have much to offer these fugitives from our overly complex society. For them I have tried to be very specific. I have not assumed that they recognize a sweet birch tree or know the difference between a benign or poisonous sumac. If in the process I have been too detailed for those who already know such things, I offer no apology, for I want this work in its own limited way to add to the success of those who try to live close to the land.

HARD CIDER

Although the early colonists came with their beer and brought the knowledge of malting with them, their drinking habits soon changed from beer to cider. English grains did not thrive during the first years of settlement before the tree stumps and roots rotted away enough so the fields could be properly plowed, and Indian corn seems to have resisted every attempt to produce a successful malt. Apple orchards were planted extensively, and in a few decades every prosperous farm had its apple orchard. Cider became plentiful and cheap. Roads were poor; markets for fresh fruits were lacking and essentially the entire crop of apples went into the manufacture of cider. This was not because apples were not good to eat. The fruit was widely used in the autumn, but the season was not long and the quantity necessary for this demand was not large. One good apple tree yields up to ten bushels of fruit and even a large family cannot eat many bushels.

Sweet cider keeps for less than a week at room temperature before it starts to ferment actively to hard cider. There are natural yeasts on the apples (the so-called "blush" on fresh apples), so that nothing needs to be added, and it is only toward the end of the fermentation that there was any risk of making vinegar instead of cider in case not enough carbon dioxide was being produced. In the violent part of the process, the tumultuous or foaming fermentation, the danger was only that the "must" (juice) might overflow the barrel. When the fermentation slowed down, the barrel was plugged with a loose bung or small sandbag. The soft hiss of the gas coming out around the edges was called the "singing of the cider." After the singing stopped, the farmer reduced the ullage (the empty space above the liquid) either by filling the barrel to overflowing with extra cider or by dropping stones into the barrel to raise the liquid level. The whole process took a month or two. In the spring the cider was racked off into storage barrels that were filled up right to the top, the bungs were driven in hard, and the cider was aged for a couple of years before it was considered to be at its peak.

By our modern standards the hard cider that the early settlers drank was dry and not particularly alcoholic.... If the farmer had honey or sugar to spare, adding it to the sweet cider would, of course, increase the potency when fermented. During the 18th century, cider became an important export commodity from New England. To increase its alcoholic content and to improve its keeping quality, especially when shipped to hotter climates, sugar was often added. By the late 18th century the standard cider for sale in taverns ran around 7.5 per cent alcohol, the sugar content of the must having been raised from the five per cent of the cider made from pure apples alone.

For those who could spare the sugar and who wanted to make a drink that was a little special, they produced what was often called "apple champagne." Some of the cider that was racked off in the spring was put directly into bottles with a teaspoon of sugar - a process called "priming." The bottles were corked, the corks tied down, and the bottles put away in a dark corner of the cellar for a year or two. The added sugar continued the fermentation and provided a light natural carbonation to the finished cider.

TRY IT

In the fall of the year, some stands along the farm roads sell sweet cider that is unclarified and without any preservative added. This can be turned into hard cider with a minimum of effort. Five- or tengallon lots are good quantities to make at a time, although it is not necessary to press that much sweet cider all at once, since you can add subsequent amounts to the fermenting batch. Make or buy a suitable amount of sweet cider and put it in a carboy or barrel.

The fermentation uses up the sugar, so unless you prefer quite dry hard cider, add one cup of sugar, honey, or maple syrup per gallon of sweet cider so that there will be some sweetness left over in the final liquor. Adding sugar up to a certain point will increase the alcoholic content of the finished cider, although if you add too much, the fermentation will be inhibited.

Add a cake or package of yeast. Seal with a fermentation lock by bubbling the emitted gas through water and ferment to completion. This will take a month or so. Be careful not to fill the barrel too full, since this fermentation starts out violently and you can easily overflow your barrel. When the fermentation has ceased, siphon off the must from the lees into another barrel. Bung it lightly for a week to make sure that any fermentation that was stimulated by the racking will have stopped, then drive the bung in firmly with a mallet. The cider should age in this barrel a year or so.

In general, people in colonial New England drank their beer and cider still, although sometimes their drinks were naturally carbonated by being sealed before fermentation was complete. In this modern day, effervescent beers and ciders are more compatible with other drinks we are used to. If you find still beer or cider unappetizing, you can easily give it a bit of fizz. Instead of aging in a barrel, siphon the cider into bottles, adding a teaspoon of sugar per quart. Further fermentation will provide a light natural carbonation to the finished cider. Use crimp-type caps or wire down the corks to withstand the added pressure. Let this cider ripen in the bottles for some months while the fermentation takes place.

This aging in bottles often goes by the German name of "lager" fermentation and it may produce one problem for the modern drinker who is accustomed to clear drinks, since this further fermentation will produce lees in the bottom of the bottle. When the pressure is released, these lees will be stirred up and the cider will appear muddy. This does not affect the taste, but if for cosmetic reasons you want the cider to stay clear, there is a fairly simple way of proceeding. Store the sealed bottles upside down during the lager fermentation (a few months). After the sediment has settled in the neck, put the upside down bottles in the freezer. When the cider is solid, remove the frozen lees which will be in the neck and reseal while still frozen. If you use plastic champagne stoppers, which are hollow, all the sediment will come out with the stopper.

One word of caution: Do not try this technique with beer. Cider freezes into "slip ice," which is fairly soft and does not exert great pressure on the bottle. Beer, which behaves like water, freezes into a solid cake with a large coefficient of expansion, which will almost certainly shatter the bottle.

ROYAL CIDER

Although hard cider is alcoholic, the five per cent content that results from fermenting the sweet cider made only from New England apples does not guarantee that the cider will keep well, particularly in hot weather. When the farmer could afford the time and money to do so, he would spike the cider with a distilled liquor. If he used apple brandy, the result was a very highly regarded drink known as Royal Cidei or Cider Royal. This combination was often fortified up to the alcoholic concentration of table wine.

Under this same name was another drink that was even stronger. Apple wine was fortified with apple brandy to give a drink much like sherry. In fact it was at times "sherryized," which means that the barrels containing the wine and brandy mixture were left out in the hot sun to blend. Apple brandy is a fairly harsh liquor, and Royal Cider was sometimes mellowed by aging the beverage after sherryizing. The mixture was sealed in a bottle in which an apple had been grown, not only to improve the taste but to delight the eye as well. A full-sized apple inside a bottle is quite a sight the first time it is seen. The farmers used to amaze strangers with tall tales of special shrink-drying techniques or their skill at "milking" whole apples through the necks of bottles

You, Too, CAN DO IT

A convenient way to try out this drink is to take four quarts of apple wine and add a "fifth" of apple brandy (often sold in liquor stores under the erroneous name of applejack). This makes five quarts of Royal Cider. It can be kept hot all summer by storing the bottles in a hot attic. Use champagne bottles and either close them with crimp caps or wire down the corks, because when they get hot, the pressure in the bottles builds up.

To try the apple-aging technique, you must have available a bearing apple tree. Select a perfect fruit early enough in the spring so that the small apple will pass through the neck of whatever bottle you plan to use. A demijohn or fiasco (a roundbottom bottle covered with straw) is very convenient, since the wickerwork makes it easy to tie to. You can use a decanter, although it is a little hard to get the apple out if you want to use the decanter for something else later. Strip off all the side twigs and leaves from the branch holding the apple and slip the fruit into the center of the bottle. Tie the bottle to a convenient branch with the neck sloping downward for rain drainage. Plug the entrance of the bottle with cotton to keep out the bugs and worms and leave it to grow for the whole summer. In the fall, when the fruit is ripe, it is easy to pull the stem off the apple. Rinse the bottle and apple to clean it of bark and other debris and fill it up with sherryized Royal Cider. If you keep the apple covered with liquid, it will last for years. To be effective as an aging agent, the apple should be in contact with the liquor for not less than six months.

APPLE WINE

Hard cider was the main thirst-quencher for the early settlers, but when sugar in some form was available, it was not uncommon to make a more alcoholic wine by continuing the fermentation beyond the hard cider stage. This was a process separate from the cider-making. After the cider was fermented to completion, it was racked off into another barrel to separate it from the lees; raisins and sugar were added, and it was fermented a second time to raise the alcoholic content from the five per cent of cider to about 12 per cent of apple wine. Maple syrup was often used as the sugar, since the timing of the processes was just about right. Fresh cider that started to ferment in October had gone as far as it could go, if kept in the warmth of the house, by March, when the sap began to run. The farmer therefore did not have to store the syrup but could add it directly to the cider barrel. Other common sugars that were used were honey, in which case the wine was called "cyser," or imported cane sugars, usually of the crude variety we now call "brown."

In restarting the second fermentation, added yeast was sometimes necessary but usually not. The farmers made their raisins by air-drying bunches of grapes hung from the house rafters so that the wild yeasts that were on the grapes were available to go to work as soon as the raisins were added to the cider.

MODERN MAKING

Fill a ten-gallon barrel right up to the top with sweet cider and close with a fermentation lock. You can ferment this to hard cider with or without yeast. If you add yeast it will take two or three weeks; without added yeast it will take a month or more. When fermentation is complete, rack off the liquid to another barrel. Add to this second barrel four pounds of sugar or an equivalent amount of honey or maple syrup, and three pounds of raisins, and reseal with a fermentation lock. Fermentation should start up again and continue for a few months. If it does not, add more yeast. Let the barrel sit for a few weeks after the gas has stopped coming off, so that the lees will settle out, then rack the wine off into another barrel to age. This wine must be aged for at least a year before using.

A variation which results in a mellower apple wine is to use brown sugar. In that case, keep the wine under its water seal for a few months after the bubbling has stopped. Brown sugar tends to keep the second fermentation going, and you may have difficulty if you try to start the aging too soon.

APPLEJACK

Applejack (or, as it was also called, "cider oil") was one of the most common strong drinks made in the old New England countryside. Whereas the other strong drinks were made by distilling, either in small quantities and very slowly on the back of the kitchen stove or in larger quantities requiring a lot of work in gathering the wood and tending the fires, applejack came from hard eider by the process of fractional crystallization by freezing, which the weather took care of automatically. When colored by darkkerneled Indian corn, it was said to taste so much like madeira wine that Europeans drank it without realizing the difference.

The potency of the result is directly proportional to the coldness of the weather. The water freezes, forming ice that floats to the surface. The colder the temperature, the more ice is frozen out. Normal diurnal temperature fluctuations allow the liquid with higher alcoholic content to drain out of the crystal lattice of the ice during the day and refreeze during the night, gradually forming a greater and greater separation between the ice and the liquor.

Real applejack cannot be made unless the temperature goes down below 0° Fahrenheit. However, a continuous variety of wines can be made depending on the severity of the winter. Applejack made in southern New England rarely exceeds about 25 per cent alcohol, but in the north its alcoholic content can get much higher. The records show that the New England weather has not changed in character since colonial days, and the common tales one hears from the farmers of the tremendous potency of their grandfather's applejack do not come from the proof-strength of the drink. Stories get taller in the telling, and some of the alleged effects of applejack are undoubtedly embroidery. On the other hand, fractional crystallization is a fairly common chemical technique for purifying crystals, which implies that the ice gets purer and purer as the process goes on and the impurities become concentrated in the remaining liquid. The after-effects of drinking can often be laid much more to "impurities" in strong drink than to the actual alcoholic content, so that the reputation of applejack may be quite justified. The state of intoxication that followed unrestrained drinking of applejack was called "apple palsy."

MODERN EQUIVALENT

If there is any place where one can buy real applejack I have not been able to find it. If you want to taste this most popular of old New England drinks you will have to make it. What is sold in New England shops as applejack and from Normandy as calvados is apple brandy, not real applejack. Brandy is made by distilling, not freezing, and is very different. Distilling purifies the alcohol and leaves the impurities behind, to be discarded, while freezing purifies the water (to be discarded) and leaves all the taste in the alcohol.

To make applejack start with no less than five gallons of sweet cider and ferment it under a water seal to completion. This will take about a month. The hard cider then should be racked off into another container, which should be put outside to freeze. If the climate is sufficiently severe to assure an extended period of time when the nights will be below zero, the cider may be frozen in a barrel and tapped some time in midwinter after the temperature has dipped to - 20° F or lower. In northern New England, you do not really have to see what is going on, but can let nature take its course unsupervised. However, if temperatures of zero or below occur only a few times during the winter, you have to attend to the separation with more care, and a transparent carboy should be used so that you can observe the rate of progress of the fractional crystallization.

When the nights have been cold enough (and the days not so warm as to melt everything) to freeze the top layer of the cider to thickness of an inch or more of very white ice, siphon off the liquid into another carboy, leaving the ice behind as waste. Keep fractionating the cider in this fashion all winter. As the volume of liquid gets less, it becomes convenient to move to gallon jugs; rather than use a siphon, the liquid can be poured off through and around the ice.

Good applejack will result if the concentration gets to a point where it will no longer freeze at zero or below. This will amount to a reduction in liquid volume of at least an eighth to a tenth of the amount you start with. The stronger the concentrate, the smaller the yield.

Applejack is a very dry drink and as far as we can tell, colonial New Englanders drank it just as it came from the barrel. However, our modern taste requires that we treat applejack as a liqueur, which is customarily sweet. It fits the modern palate better to sweeten the liquor as it is bottled. The bottling should be done while the applejack is still cold. Add one tablespoon full of activated charcoal (to help it age) and four tablespoons of sugar to each pint. Cap, and age for at least two years.

In southern New England it is by no means certain that the temperature will always be cold enough to make good applejack every year. However, even if the temperature only gets down to 5° or 10°F, the concentrate is still worth bottling and ageing as it makes a pleasant light apple wine. Of course, it is perfectly practical to bottle what does not concentrate suf- ficiently one year and keep it to try the next. To do this, seal the concentrate in quart bottles, then, about the following January, empty these bottles into gallon jugs and continue the freezing process.

Reprinted by permission of the University Press of New England from Wines & Beers of Old New England. Copyright © 1977 by Trustees of Dartmouth College.

Excerpted from Wines & Beers of Old New England. The author, SanbornC. Brown '35, says, "I thought I was agood physics teacher at but,compared with 37 years of physicscourses, nothing was nearly as popular as the seminars I gave to studentsand staff on the technology of winesand beers of old New England. As aresult, as soon as I retired I sat downand wrote up my research into a bookwith the same title." The book will bepublished later this fall by the University Press of New England.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

October | November 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Bakke Case

October | November 1977 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

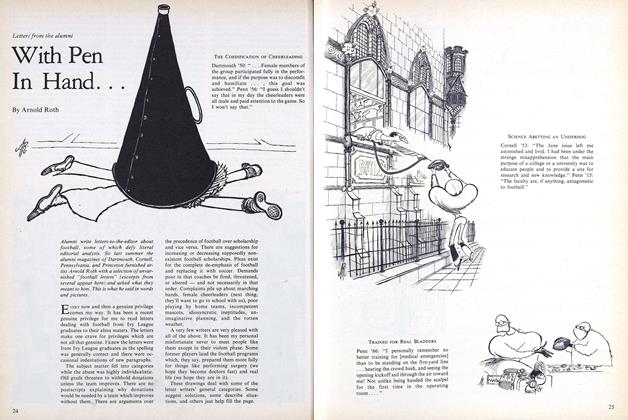

FeatureWith Pen In Hand...

October | November 1977 By Arnold Roth -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October | November 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Article

Article"My hardships were excessive"

October | November 1977 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

October | November 1977 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSix Alumni Awards Bestowed

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureJeffrey Hart Professor of English 20 million readers in a single column

January 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHandsome Facade

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureSeeing Farther than the Green

September 1976 By BLISS K. THORNE and NANCY DECATO -

Feature

FeatureChanging Values in American Society

JANUARY 1970 By HAROLD L. BOND '42, PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH -

Feature

FeatureLife After the Presidency

NOVEMBER 1984 By Shelby Grantham