PARKHURST HALL is not one of Dartmouth College's more inviting buildings. Stolid and square, it sits in the distance like a monumental tomb. The architecture can only be charitably described as eclectic. Throughout my college career I have assiduously avoided the place, and with good reason. Therein vanished the sore-handed window punchers, paint-stained art critics, remorseful vandals, and penitent drunks: a select few of the ordinarily nice people who become the neo-Huns of the Hanover Plain on any given weekend. On Monday mornings these companions of Friday night solemnly marched through the granite portal,, and were that afternoon dispatched to parts unknown. I decided that if they wanted me, they would have to come get me. I guarded my anonymity. The casual "good morning" of a passing administrator might have sent me packing for Australia.

College, being a citadel of enlightenment, is no place to harbor such superstitions. And I am told that each week the President holds student office hours for the express purpose of dispelling my doubts or airing whatever else is on my mind. So on a tentatively autumnal afternoon I set out to meet John G. Kemeny, the mathematician-philosopher with a list of accomplishments longer than the faces of the College endowment officers. His presence is felt everywhere at the College: in the computer system he (and others) designed, in the math classes he teaches, and in the daily operations of the resident bureaucracy. Somehow the diverse functions of the College are all at least partly attributed to him: He is Dartmouth's nearest equivalent to a First Cause. To paraphrase Voltaire, if he did not exist, he would have to be invented.

Kemeny myths abound. In local legend he is portrayed both as Superman and Dr. Strangelove, Cicero and Caligula. His accessibility to students is both a matter of pride with him and a selling point for the admissions office, yet he personally does not have a high profile on campus. He prefers to work his effects subtly, with a minimum of ceremony. He is übiquitous without being familiar. While other top Dartmouth administrators are regarded as favorite uncles, the President remains an enigma.

Parkhurst's facade is strangely similar to the entryway at Chartres cathedral. The doors seem 12 feet high and are ponderously foreboding. They move only with great reluctance. There are no gargoyles guarding the passage, but the gargantuan doors block the path to the temple. Once inside, the way to the President's office follows a ziggurat course up a circli ng staircase to the most commanding position - the high ground. His office is not to be mistaken for a professor's cubicle: A spacious parlor houses the desks of three secretaries without seeming at all crowded. Off to one side of this room is a passageway to Kemeny's personal offices, with yet another set of imposing doors. These are of rich mahogany, with "The President" understatedly inscribed in faded gold letters.

I am politely asked to stop blocking the entrance, so I find a perch on the arm of a large leather couch, where four of my fellow supplicants calmly await their interview. Some have come to solicit recommendations, others are here to urge affirmative action. The rest of us concentrate on the contents of a large candy jar invitingly placed on an end table. Not wanting to be caught pinching a Hershey bar, I chew instead on my pen. Just as I begin to relax an irrational panic grips me. I realize that I have walked off, unthinkingly of course, with a very old and rare library book. Guilt settles on my shoulders and I try to stash the pilfered volume under the couch. I feel like Raskolnikov over a fossilized book. Will he know? I wonder how real miscreants feel here. What if, for example, I had just spray-painted "coeds must go" in fluorescent orange on the di Suvero sculpture?

Voices murmur deferentially until the arrival of another titan: Leonard Rieser, dean of the faculty. He bounds in, asking, "Does John exist?" This really unravels me. If Rieser doesn't know, who does? I decide that it would be presumptuous of me to waste the President's time, even if he does in fact exist, and I head for the exit. At this moment of irresolution the mahogany doors part and a rumpled man emerges, calls out "next," and returns to sanctuary. His manner is pleasantly relaxed, like that of a small-town dentist. Encouraged, I follow him despite a long standing fear of dentists, especially smalltown dentists. For an instant the Wizard ofOz comes to mind, and I recall Dorothy's initial disillusion. Finding the all-seeing Oz to be a mere lever-pulling professor, she doubts his powers. Perhaps we prefer our leaders to be larger than life?

Our conversation is nothing unusual: The President's job, students, the fund drive, his image, and his aversion to "the 15-second conversation" are all touched upon. What is unusual is the man. His casual demeanor puts me at ease immediately. He is gracious and interested, despite what appears to be a naturally reserved personality. "It really bothers me," he confides, "that some people think you cannot care about human beings if you are involved with technology."

Paradoxically, the man most responsible for the computer age at Dartmouth has a dread fear of airplanes. "I like," Kemeny says, "the things I do on the road - talking with alumni and prospective students especially - but I absolutely loathe travel." For a moment I suspect that he knows something we sanguine fliers are unaware of. But I am secretly pleased that this most rational man has, like me, irrational fears. "Anywhere from three to ten students usually show up for the weekly hours," he estimates, "and their concerns vary greatly." Some come in with brainstorm ideas for the College: "Most of these are impractical, but every year I really use two or three of them."

I am in no hurry to leave the office and end my time in the limelight, but others wait outside. My curiosity is satisfied. I walked in, at my own leisure, and met the President of my college. Not only did I meet him, we talked at length and he was genuinely interested in me. Dartmouth College, I conclude, is a humane institution, as advertised.

On the matter of presidential accessibility,see also "Vox" in this issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFie on the Flush Toilet

November | December 1977 By Harold H. Leich -

Feature

FeatureSee How They Run

November | December 1977 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

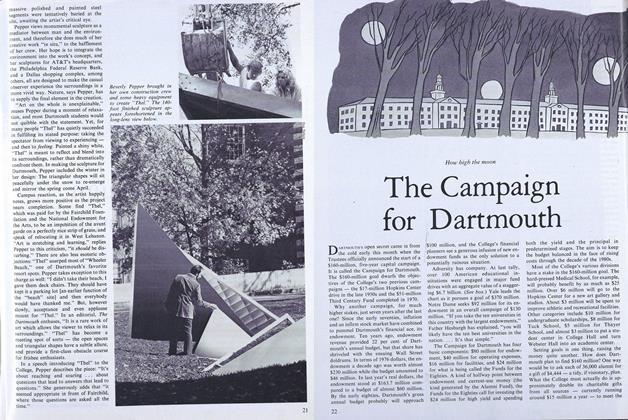

FeatureThe Campaign for Dartmouth

November | December 1977 -

Article

ArticleThe DCMB Double-entendre March

November | December 1977 By Anne Bagamery -

Article

ArticleDick's House Is Her House

November | December 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleTheir Fathers' Sons

November | December 1977

MARK HANSEN '78

Article

-

Article

ArticleCLASS PUBLICATIONS

April 1924 -

Article

ArticleNews of The Faculty

March 1940 -

Article

ArticleCollege Board Tests Adopted

January 1952 -

Article

ArticleThree Grants

April 1956 -

Article

ArticleA GERMAN REVIEW OF RICHARD HOYEY

January, 1910 By Eugene F. Clark '01 -

Article

ArticleFreshman Eligibility OK'd by Ivy Presidents

APRIL 1971 By JACK DEGANGE