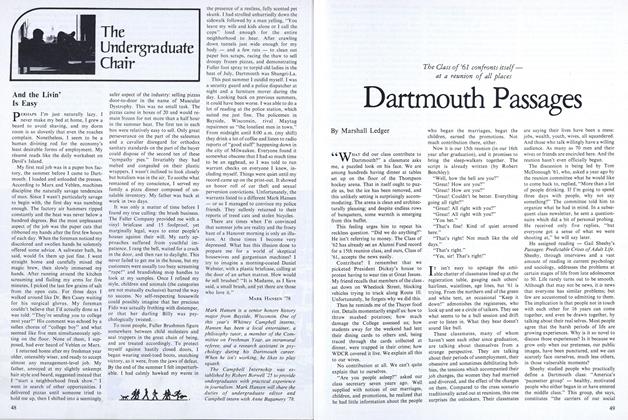

PERHAPS I'm just naturally lazy. I never make my bed at home, I grew a beard to avoid shaving, and my dorm room is so slovenly that even the roaches complain. Nonetheless, I seem to be a human divining rod for the economy's least desirable forms of employment. My resume reads like the daily worksheet on Devil's Island.

My first real job was in a paper box factory, the summer before I came to Dartmouth. I loaded and unloaded the presses. According to Marx and Veblen, machines discipline the naturally savage tendencies of man. Since I wasn't particularly savage to begin with, the first day was numbing enough. The factory air hammers ripped constantly and the heat was never below a hundred degrees. But the most unpleasant aspect of the job was the paper cuts that ribboned my hands after the first few hours of each day. When the foreman noticed my discolored and swollen hands he solemnly offered some advice. A saltwater bath, he said, would fix them up just fine. I went straight home and carefully mixed the magic brew, then slowly immersed my hands. After running around the kitchen screaming and flailing my arms for five minutes, I picked the last few grains of salt from the open cuts. For three days I walked around like Dr. Ben Casey waiting for his surgical gloves. My foreman couldn't believe that I'd actually done as I was told: "They're sending you to college next year?" His comment was echoed by a sullen chorus of "college boy" and what seemed like five men simultaneously spitting on the floor. None of .them, I supposed, had ever heard of Veblen or Marx.

I returned home after my freshman year older, ostensibly wiser, and ready to accept almost any management-level job. My father, annoyed at my slightly unkempt hair style and beard, suggested instead that I "start a neighborhood freak show." I went in search of other opportunities. I delivered pizzas until someone tried to hold me up, then I shifted into a seemingly safer aspect of the industry: selling pizzas door-to-door in the name of Muscular Dystrophy. This was no small task. The pizzas came in boxes of 20 and would remain frozen for not more than a half hour in the summer heat. The first ten in each box were relatively easy to sell. Only great perseverance on the part of the salesman and a cavalier disregard for orthodox sanitary standards on the part of the buyer could dispose of the second ten of these "sympathy pies." Invariably they had melted and congealed on their plastic wrappers. I wasn't inclined to look closely but botulism was in the air. To soothe what remained of my conscience, I served my family a pizza dinner composed of unsalable inventory. My father was back at work in two days.

It was only a matter of time before I found my true calling: the brush business. The Fuller Company provided me with a vinyl briefcase and 15 foolproof, yet marginally legal, ways to enter people's houses against their will. My early approaches suffered from youthful impatience. I rang the bell, waited for a crack in the door, and then ran to daylight. This never failed to get me in the house, but my customers were usually too busy screaming "rape!" and brandishing mop handles to look at my samples. Once I refined my style, children and animals (the categories are not mutually exclusive) barred the way to success. No self-respecting housewife could possibly imagine that her precious Fido was actually frothing with distemper, or that her darling Billy was psychologically twisted.

To most people, Fuller Brushmen figure somewhere between child molesters and seal trappers in the great chain of being, and are treated accordingly. To protect myself against hastily closed doors, I began wearing steel-toed boots, snatching victory, as it were, from the jaws of defeat. By the end of the summer I felt imperturbable. I had calmly hawked my wares in the presence of a restless, fully scented pet skunk. I had strolled unhurriedly down the sidewalk followed by a man yelling, "You leave my wife and kids alone or I call the cops" loud enough for the entire neighborhood to hear. After crawling down tunnels just wide enough for my body - and a few rats - to clean out paper box scraps, racing the thaw to sell droopy frozen pizzas, and demonstrating Fuller foot spray to torpid old ladies in the heat of July, Dartmouth was Shangri-La.

This past summer I outdid myself. I was a security guard and a police dispatcher at night and a furniture mover during the day. Looking back on previous summers, it could have been worse. I was able to do a lot of reading at the police station, which suited me just fine. The policemen in Bayside, Wisconsin, rival Maytag repairmen as "the loneliest men in town." From midnight until 8:00 a.m. (my shift) they drink a lot of coffee and listen to radio reports of "good stuff' happening down in the city of Milwaukee. Everyone found it somewhat obscene that I had so much time to be an egghead, so I was told to run warrant checks on everyone I knew, including myself. Things were quiet until my record came up on the print-out. It showed an honor roll of car theft and sexual perversion convictions. Unfortunately, the warrants listed to a different Mark Hansen - or so I managed to convince my police friends. They sullenly returned to their reports of treed cats and stolen bicycles.

There are times when I'm convinced that summer jobs are reality and the frosty haze of a Hanover morning is only an illusion. At these times I become very depressed. What has this illusion done to prepare me for a world of skeptical housewives and gargantuan machines? I try to imagine a morning-coated Daniel Webster, with a plastic briefcase, calling at the door of an urban matron. How would he sell brushes? "It is Madame, as I have said, a small brush, and yet there are those who love it."

Mark Hansen is a senior honors historymajor from Bayside, Wisconsin. One ofthis year's Whitney Campbell interns,Hansen has been a local entertainer, aphilosophy tutor, a member of the Committee on Freshman Year, an intramuralreferee, and a research assistant in psychology during his Dartmouth career.When he isn't working, he likes to playsquash.The Campbell Internship was established by Robert Borwell '25 to provideundergraduates with practical experiencein journalism. Mark Hansen will share theduties of undergraduate editor andCampbell intern with Anne Bagamery '78.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureScience and Technology Under Siege

September | October 1977 By Thomas Laaspere -

Feature

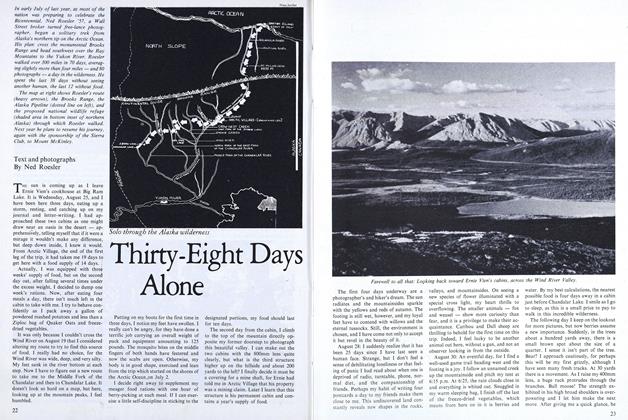

FeatureThirty-Eight Days Alone

September | October 1977 By Ned Roesler -

Feature

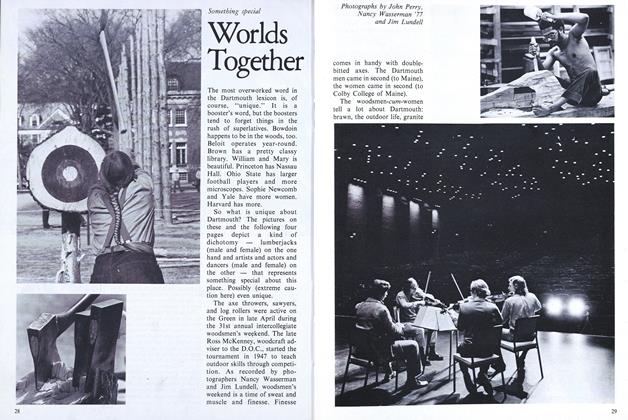

FeatureDartmouth Passages

September | October 1977 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

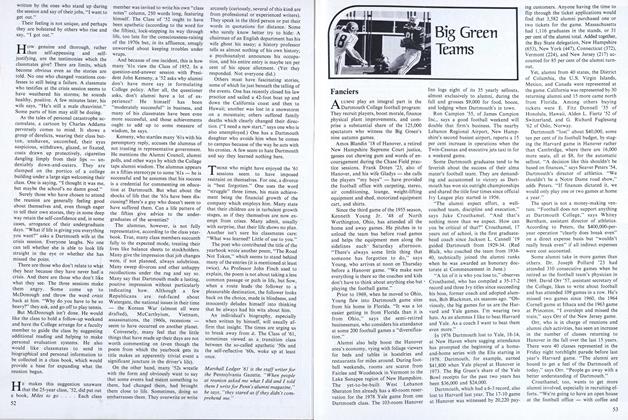

FeatureWorlds Together

September | October 1977 -

Article

ArticleFanciers

September | October 1977 By BRAD HILLS '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1927

September | October 1977 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK