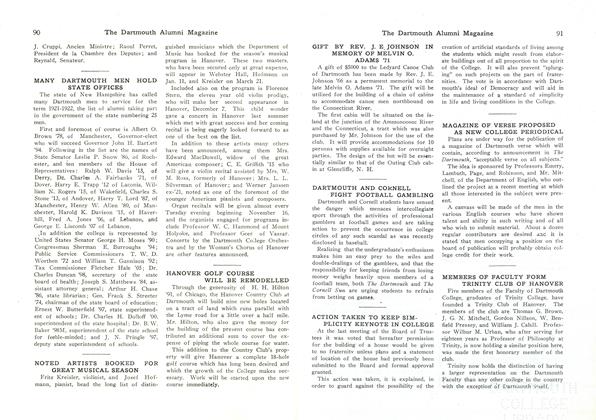

BOB MacArthur '64 is the director of the Dartmouth Outward Bound Center and as such he serves two masters: the College and Outward Bound Inc. The aims of the two organizations merge under the auspices of the Tucker Foundation. Outward Bound, an educational association of six schools and one center, is engaged in propelling students into value- forming situations: students are immersed in what is usually an intensely challenging, month-long outdoor experience. The objective is to provide the opportunity for students to develop what used to be called character.

What is an ordained Episcopal priest like MacArthur, who majored in Greek and Roman studies and lettered as a varsity pitcher, doing as director of such a program? In part, he is involved in carrying out the Tucker Foundation's charge to further the spiritual and moral life of the College. It also has something to do with putting faith, and faith in people, to work both inside and outside the church. After obtaining his master of divinity degree in 1967 from Berkeley Divinity School at Yale, he became curate at Hanover's St. Thomas' Episcopal Church — where he still serves as a priest associate — and worked as the Episcopal student chaplain. From 1969-1970 he was director of internship programs at the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown. North Carolina. His involvement with Outward Bound began as a student at the Colorado Outward Bound School, followed by a stint as an assistant instructor at the Hurricane Island School in Maine and as an instructor at the North Carolina School. He became program director of Dartmouth's center in 1970 and has been general director since 1972.

I wanted to spend some time with MacArthur in order to find out more about him and to do some climbing, and MacArthur wanted a chance to expose his friend Hank Taft, president of Outward Bound Inc., to winter camping. Two heavy snow storms had hit the North Country and it seemed a shame to be sitting behind desks, letting the snow go to waste. We decided on a three-day snowshoe trip to the summit of Mt. Moosilauke.

MacArthur had been up the steep Beaver Brook trail, which heads out of Kinsman Notch, the week before on a staff training venture. He said that although it had been a "good workout," his party of eight had easily made two miles on snowshoes to the saddle between Mt. Blue and Mt. Jim in less than four and a half hours. Our plan called for us to make it to the saddle early Friday afternoon, set up our tent, and stomp down the snow so we could cut it into blocks the next day for an igloo. Depending on the weather, we could hike the mile and a half to the summit of Moosilauke on Saturday afternoon or Sunday morning. It sounded perfect — not too far to go and plenty of spare time to practice some camping and climbing skills.

We sorted and packed our equipment at MacArthur's house the evening before the trip, dividing the food and group gear between us. MacArthur and Taft debated the merits of slightly different ways of dressing for a winter's excursion. Bob preferred a fishnet shirt to a turtleneck under his wool shirt, advised against long johns, and recommended only one pair of heavy wool socks in our G.I.-type Mickey Mouse boots. Made of rubber and well insulted and sealed to prevent the absorption of moisture, they are much warmer (rated to —30°) than leather boots or felt- insulated packs.

Our uniforms were fairly standard. We wore woolen stag pants (the type preferred by loggers), two heavy wool shirts or sweaters (wool retains some of its insulation value even when wet), a down parka, an anorack or 60-40 parka (a medium- weight windbreaker that sheds snow and light rain) and windpants. We each had balaklavas (they fold down to form face masks) and wool mittens with leather or nylon shells. Taft and I also brought gaitors (to keep snow out of the tops of our boots) and down mittens. The trick to dressing for winter is to layer clothing to permit adjustments for comfort. If a hiker has only one heavy parka he is either too hot while on the move or too cold when he takes it off.

Friday evening, our first night out, we were settled in the spacious four-man McKinley tent by 7:30. Although the temperature outside was about 10°, with two candles burning inside it was light and warm enough to take notes without flashlight or gloves.

My journal records that it was 1:30 p.m. by the time we had eaten our lunch, left the van, and started up the Beaver Brook trail — quite a bit later than our schedule dictated. The terrain was quite flat and the snow deep. Somebody had been on the trail ahead of us, although not on snowshoes, and judging from their foot-prints they had been sinking at least to their knees. We were glad to have our snowshoes although at first we suffered the inevitable fumbling with the bindings as they stretched and slipped off the toes of our boots. MacArthur and Taft were using what is probably the best all-around snowshoe for New England terrain: Green Mountain bearpaws with rawhide lacing. Not too large, good for maneuverability in dense brush, they also have a well-turned up toe which is helpful for descending in deep snow.

Bob started out breaking trail, Hank was in the middle, and I brought up the rear. Just as we seemed to be getting into good rhythm, the trail headed up steeply beside Beaver Brook. The snowshoes couldn't track on such a steep pitch with all the new snow we had, but with our heavy packs — about 60 pounds each — it seemed we wouldn't get anywhere without them. But we had to move, so we strapped our snowshoes to our packs and plunged in. We went on for half an hour, MacArthur still leading, until the track we had been following ended. Its makers had very sensibly turned around.

From now on, since the work was more difficult, we switched leads frequently. It was exhausting to push for more than a few minutes through snow that was sometimes waist deep. The trick was to try to figure exactly where the real trail was. If one of us wandered off what had been packed underneath the week before, he fell into holes so deep he had to be pulled out. At this pace we obviously wouldn't reach our desired destination, and with darkness coming on we chose a slight dip in the trail, tromped down and leveled the snow for our tent, and started melting snow for water for dinner.

For dinner we had MacArthur's favorite dish: Turkey Good 'n' Hearty. I cooked, and after my partners tasted the result they relieved me of any further culinary responsibilities. The only real problem with the main course was that I chose a pot too small for the six-serving portion. With no way to add sufficient water, Turkey Good 'n' Hearty remained a semi-stiff paste. After dinner, the bowls were cleaned by a serving of cocoa or hot fruit drink.

A wintertime hiker cannot simply roll into his sleeping bag and fall asleep. There is a series of important rituals to observe first. As soon as the tent is set up, foam sleeping pads (not air mattresses, which conduct cold) should be laid out and the down sleeping bags unstuffed from their sacks and shaken to cause them to loft — to puff up for greater insulation. Taft's pad came nowhere near to matching his six- foot four-inch height, so MacArthur showed him how to put snowshoes under the end of the bag so his feet wouldn't rest on the cold floor.

After taking off our, boots, we changed wet socks for dry ones. When it is really cold, MacArthur told us, change socks two or three times a day, not forgetting to put them in a warm place so they won't be frozen in the morning. I stuffed the damp socks down the front of my long johns.

Then we took off our wool pants and spread them between the sleeping bags and foam pads as an extra layer of insulation. Wet mittens went inside the sleeping bags for drying. Our down parkas made good pillows, the extra sweaters a good layer of insulation under our backs.

We finally got in our sleeping bags, fluffed them up for greater loft, and began stashing water bottles, cameras, and breakfast food in strategic locations inside the bags.

Taft watched all these preparations with a critical eye as MacArthur explained the logic of each maneuver. After he had formed some congenial hollows for his hips and shoulders and moved his cold water bottle from its rather intimate location, he observed he was almost comfortable.

"What are we doing tomorrow?" Taft asked.

"Depends on the weather," MacArthur replied. "Push up trail as far as we can. It's bound to be heavy going, but it can't be too far to the saddle. We'll see what the weather's like. We can go to the summit or try to build an igloo. It won't take us long to come back down. From the road it's only three and a half miles to the summit ... but we've only come three quarters of a mile."

It was a beautiful night. The temperature was about 10 or 12 degrees and there was no wind. A foot of snow had been forecast but we could see stars in the sky. As MacArthur looked around the tent before blowing out the candles he smiled and said, "It's going to have to be a pretty big igloo for the three of us."

We slept late Saturday morning and didn't get out of the tent until 7:30. No snow had fallen and the temperature was about 15°. For breakfast we had hot drinks, oatmeal — to which generous quantities of margarine, brown sugar, and honey were added — bacon, and muffins fried in grease. None of us had much of an appetite. Several comments were made about the lingering effects of the previous evening's fare. While Taft was relieving himself behind a tree, the snow beneath him gave way and he fell into a hole up to his chest. The Reverend MacArthur inquired if the tumble from grace had been "ex post facto." Taft cursed and replied it had been, unfortunately, "in medias res."

We struck the tent, shook off the accumulation of snow and ice, and packed it away along with the rest of our gear. By 9:30 we were on the trail, such as it was, and were soon stripped to shirt-sleeves. The going was tough, slower than the day before, the trail steeper and the snow deeper. MacArthur and I alternated leads, swimming through drifts, trying to break a path. We hoped to reach the top of the ridge, always "just ahead," where it would be level enough for us to use our snowshoes. There was a great deal of slipping, falling into unseen holes, and general floundering. As we tired, there was less and less of the good-natured bantering that had been exchanged earlier.

Our lunch, eaten at the bottom of a particularly steep section, consisted of gorp and water. We planned to stop again, "just up ahead where it flattens out," for something more substantial. Taft was feeling ill and we blamed it, of course, on the turkey. After another hour and a half of climbing, a flat spot was reached and we took out the stove to cook some soup. Taft felt worse, we all were tired and, unsure of how far we would have to go before finding another level spot, we decided to pitch the tent where we stood. While Taft and I leveled the platform, MacArthur plied us with hot drinks and refilled all the water bottles.

MacArthur suggested that some hot stewed fruit mixed with brown sugar might be good for Taft who hadn't been able to eat much all day. I remembered that dried fruit was part of our inventory but was only able to find some rather formidable dried figs. We cooked them anyway — they swelled up to look like small, black pears — told ourselves they were good, and offered Taft the juice which he bravely tasted but firmly turned down.

Dinner was dehydrated beef and rice with, as MacArthur claimed, "a little bacon thrown in for zest." It wasn't good but it was considerably better than what I had achieved the night before. We were in our bags by 7:00. Taft was sick several times during the night, and around 2 a.m. MacArthur offered to make him something hot to drink. Taft, knowing the effort involved, thanked him but declined.

We had some snow that night and before dawn MacArthur was out of the tent making breakfast. By 7:45 we were on the trail heading down, on snowshoes at last. It was almost like being on skis on the steep sections. After only two hours of walking and a great deal of falling and sliding, we made it back to the van. I was soaking wet from the exertion (overdressed, said MacArthur) and from the amount of snow I had picked up in falling. MacArthur, I noticed, was a bit drier.

Once inside, driving back to Hanover, Taft smiled and said, "I'm glad to be back, but I want you to know I really enjoyed the experience. . . . Well, maybe 'enjoyed' isn't quite the right word. I learned a lot and appreciated that."

MacArthur laughed. "It was a good work out," he said. "I learned some things, too. I hope this doesn't discourage you from the possibilities of winter camping. If we had been two weeks earlier, when there wasn't so much snow, it would have been completely different. I mean we could have made it to where we wanted to go. You would have liked the summit of Moosilauke ... we could have built our igloo ... but wasn't it great to be out there just the same?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple...

February 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureNever Let Go

February 1977 -

Feature

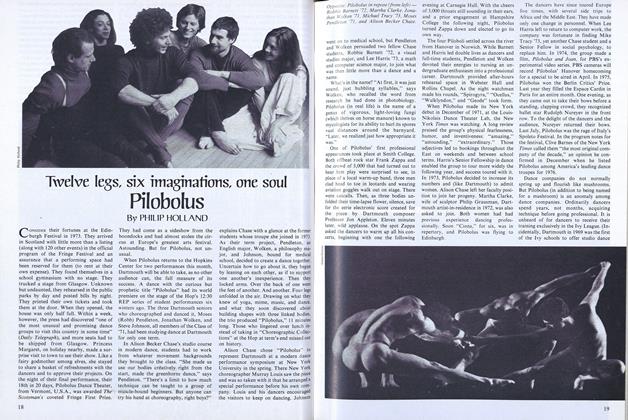

FeatureTwelve legs, six imaginations, one soul Pilobolus

February 1977 By PHILIP HOLLAND -

Feature

FeatureComposite Artist

February 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleGray Is Beautiful

February 1977 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77 -

Article

ArticleBittersweet Memories

February 1977 By ROBERT J. ZOVLONSKY '58

D.M.N.

-

Article

ArticlePaddler, Climber, 4-term Planner

May 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleClean Sweeper

DEC. 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleSignal-Caller for the Hurt

October 1978 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleStraight Shooter

December 1978 By D.M.N. -

Article

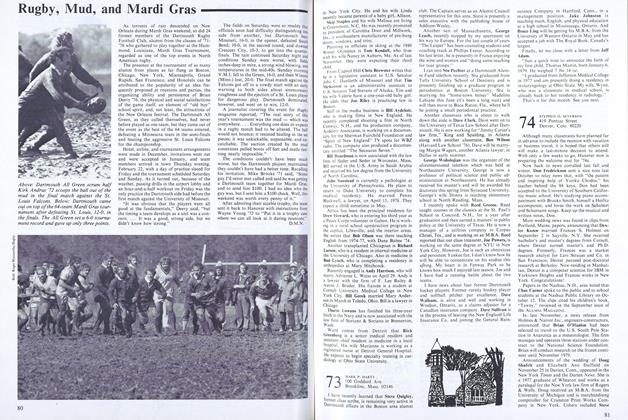

ArticleRugby, Mud, and Mardi Gras

May 1979 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleCombating the Crippler

September 1980 By D.M.N.