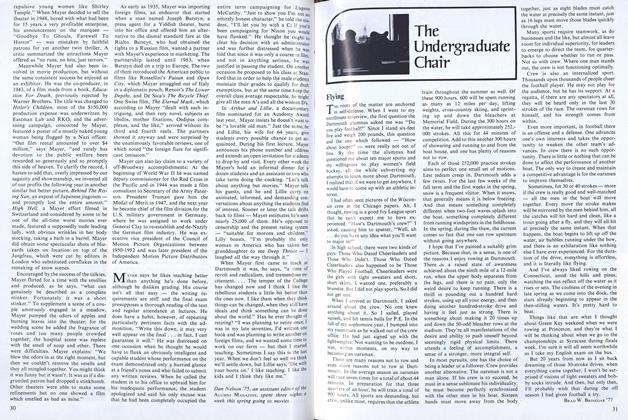

THE RECENT furor over the Trustees' decision regarding admission of more women and the petition "demanding" equal access overlooked one basic premise upon which Dartmouth College, and institutions like it, are founded: that the Trustees are, in the words of the College Charter granted by George III and defended as inviolate by Daniel Webster, "the body corporate & politick" of the College. Some protestors felt that the Trustees run on power deferred to them, power those protestors wanted back. In effect, however, they were asking the Trustees to abdicate their legal authority.

David T. McLaughlin, new chairman of the Board, told The Dartmouth, "I don't think it is the Board's duty to react to" the sentiments of the college community, because "the final decision of the Board has to be, in its own judgment, what is best for the institution in the long run." Although the views of students, faculty, and alumni were considered in this - as in other decisions - he added, the final say is the Board's responsibility.

The only way by which students, or faculty, or administrative personnel, or special interest groups could have direct control over decisions on College policy would be for those groups to have representation on the Board. Trustees who represent various constituencies do, in fact, sit on other boards of other institutions, but it seems - to me, at least - to be a system conducive to an adversary relationship rather than consensus.

If the Dartmouth Board consisted of representatives of all the College constituencies, I'm not sure they would do a better job than the present Trustees. From what I know of the current Board, they are a reasonable group. They do appear to accept and consider the merits of conflicting views they receive. They must consider the interests of three very distinct groups, each with different goals for the College: the alumni, the faculty, and the student body. To reach decisions which are both fiscally sound and satisfactory to the three is always a remarkable achievement, sometimes an impossible one.

I would suggest we retain our faith in the system. Make known your dissatisfaction with decisions contrary to your views. But make sure you understand the reasons for the decisions, in terms of all possible ramifications. Consider those decisions in the light of the overall, long-run effect on the College, as the Trustees must.

"Is IT Really True that Dartmouth A Alumni Drink More, More Often Get Divorced and Yet Earn More Money With Which to Buy Another Round Before Signing the Alimony Check than the Graduates of Any Other Collegiate Institution in the Country?" I once thought of writing that article, but the magazine budget doesn't cover headlines that long. Besides, I couldn't get the straight facts about any of the three categories.

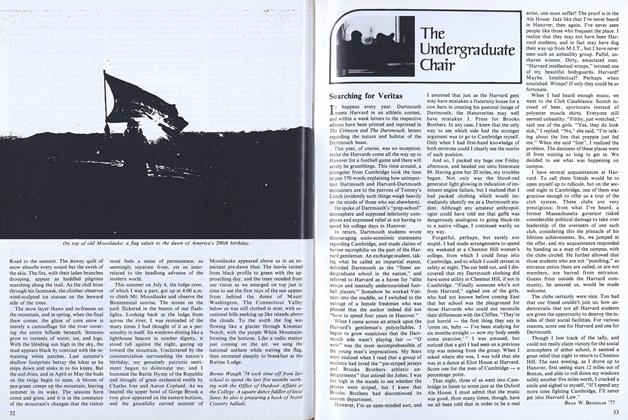

Drinking is, of course, a most popular topic of conversation among students, parents of students, alumni and friends of alumni. The stories are great: that Tanzi's used to be the largest beer distributor this side of the Mississippi River, that a Playboy college-drinking poll once excluded Dartmouth for being too professional, that F. Scott Fitzgerald might have stayed healthy if he hadn't wandered over to Alpha Delta while writing the script for Winter Carnival, that Dartmouth has beer-pong as its own sport.

Road-trips are good story-generators, too. Tales of woe and of consummate ecstasy, of good girls and bad weekends, of bad girls and incredible weekends, of good girls and future marriages, abound. Road-trips are the stuff, we are told, of which divorces are forged. Isolation in the North Woods during the week, alone with moose, and orgiastic outbursts of inhuman activity at Colby or a Seven Sisters school on the weekends: guys and girls just didn't get to know each other - emotionally, intellectually, anyway. Or so the story goes.

The Big Green. Not the replacement for the Indian. The Big Green: money. We all know that Dartmouth is the training ground for the corporate power elite, if we have listened to the demonstrators from the sixties forward who have reminded us of the "fact" every time they get upset. The Radical Union, which came into being two years ago, made a big stink about the fact that the Trustees of the College also happened to be board members of large corporations. Ergo, Dartmouth men, on the average, make more money than the graduates of other schools. True? There's really no way of telling without resorting to practices the Radical Union wouldn't condone. But if Dartmouth grads drink and are divorced more, then they better have more money, because they're just gonna need it.

How do we place this all in perspective? If Dartmouth grads do drink more, is it because of something that Dartmouth does to them? Maybe it is, but that wouldn't go far to explain why we don't have an equally high rate of drug abuse. My suspicion is that there is little bite behind the bark: the talk about Dartmouth drinking is just that. There's a lot of drinking on all college campuses.

Divorce? Dartmouth students, particularly in the past, traditionally come from upper-middle and upper class backgrounds. There is a higher incidence of divorce among such families. And children who have been exposed to divorce are more likely to be divorced themselves. So it is more likely for the Dartmouth student to be a candidate for divorce than, for instance, a student at a public university. But here's the interesting thing: a survey in the twenties, when such myths were being formed, showed that Dartmouth alumni actually had a slightly lower than national divorce rate. And today, it is hard to imagine that Dartmouth marriages are doing worse than the national norm of one out of three ending in divorce.

Money? I'm really not sure what difference it makes how much money Dartmouth grads make. Financial security is nice, but it's not much of an indicator of the person, or of the Dartmouth education. Dartmouth grads use the old-boy network just the way other Ivy. grads do, and if the system is more successful coming out of Dartmouth, it's because of the cohesion developed in Hanover. Dartmouth grads are bright, too, so there's no reason why those so inclined shouldn't do better than most people later in life.

So what it amounts to is this: whether or not unfounded, there is little clear evidence to support or deny any of the good or bad in these myths about Dartmouth. And far more important in the long run is not what Dartmouth does to or for us, but rather what we do for ourselves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDinner for the Colonel

March 1977 By BRAVIG IMBS -

Feature

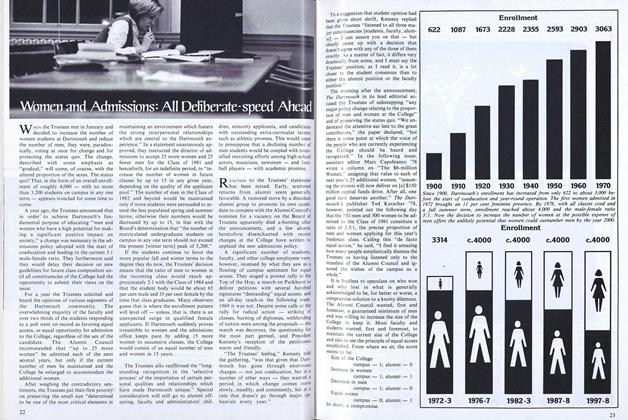

FeatureWomen and Admissions: All Deliberate-speed Ahead

March 1977 -

Feature

FeatureSleep-filled Days, Gambling Nights

March 1977 By BRAD W. BRINEGAR -

Feature

FeatureArtists

March 1977 -

Article

ArticleRambling with Melancholy

March 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleA Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 By S.G.