ARTHUR LOEB MAYER, visiting professor of drama and lecturer in film at Dartmouth and other places, sometimes describes himself as "an old and thoroughly unreliable publicity man, a strictly commercial character, wholly unfit for academic responsibilities." He describes his careers as movie publicist, exhibitor, and distributor as "three of the supposedly lowest forms of human life" and refers to his job in advertising as "the world's second oldest profession." He isn't to be entirely believed: He is old - he turned 91 on May 28 - but only in years. In 1953, at an age when most men are retired, Mayer wrote his first book, MerelyColossal, a lighthearted look at the movie industry he grew up with, and a few years later he published The Movies, a respected history of cinema written in collaboration with the late Richard Griffith, curator of film at the Museum of Modern Art. As for his suitability for academic responsibilities, Mayer has been credited with being one of the first to obtain recognition for film as an art; he's taught at a dozen colleges or universities during the past 15 years; received a doctorate in humane letters from Dartmouth in 1972 and from Clark University this spring; and presently teaches economics of film at the University of Southern California in the fall, art of the cinema at Stanford in the winter, and history of motion pictures at Dartmouth in the spring.

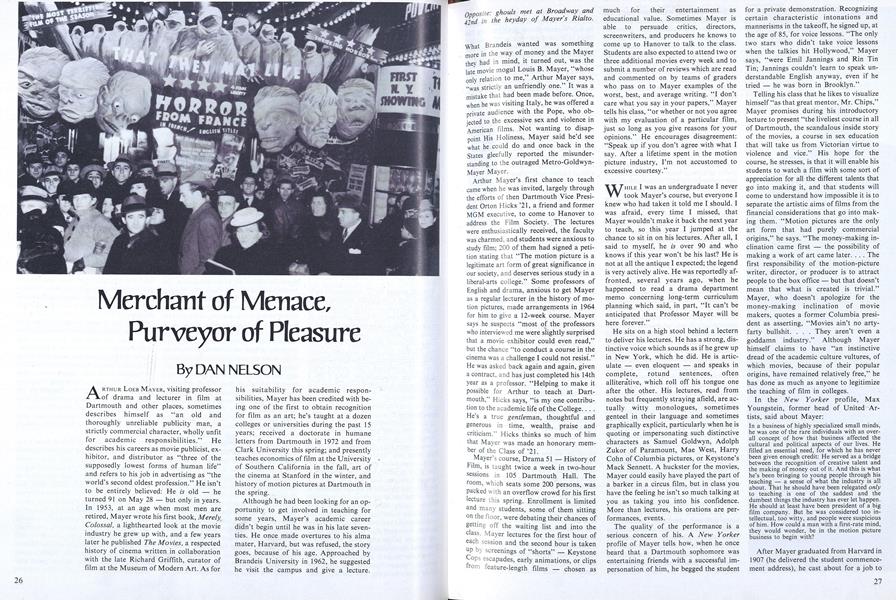

Although he had been looking for an opportunity to get involved in teaching for some years, Mayer's academic career didn't begin until he was in his late seventies. He once made overtures to his alma mater, Harvard, but was refused, the story goes, because of his age. Approached by Brandeis University in 1962, he suggested he visit the campus and give a lecture. Opposite: ghouls met at Broadway and42nd in the heyday of Mayers Rialto.

What Brandeis wanted was something more in the way of money and the Mayer they had in mind, it turned out, was the late movie mogul Louis B. Mayer, "whose only relation to me," Arthur Mayer says, "was strictly an unfriendly one." It was a mistake that had been made before. Once, when he was visiting Italy, he was offered a private audience with the Pope, who objected to the excessive sex and violence in American films. Not wanting to disappoint His Holiness, Mayer said he'd see what he could do and once back in the States gleefully reported the misunderstanding to the outraged Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Mayer.

Arthur Mayer's first chance to teach came when he was invited, largely through the efforts of then Dartmouth Vice President Orton Hicks '2l, a friend and former MGM executive, to come to Hanover to address the Film Society. The lectures were enthusiastically received, the faculty was charmed, and students were anxious to study film; 200 of them had signed a petition stating that "The motion picture is a legitimate art form of great significance in our society, and deserves serious study in a liberal-arts college." Some professors of English and drama, anxious to get Mayer as a regular lecturer in the history of motion pictures, made arrangements in 1964 for him to give a 12-week course. Mayer says he suspects "most of the professors who interviewed me were slightly surprised that a movie exhibitor could even read," but the chance "to conduct a course in the cinema was a challenge I could not resist." He was asked back again and again, given a contract, and has just completed his 14th year as a professor. "Helping to make it possible for Arthur to teach at Dartmouth," Hicks says, "is my one contribution to the academic life of the College.... He's a true gentle man, thoughtful and generous in time, wealth, praise and criticism." Hicks thinks so much of him that Mayer was made an honorary member of the Class of '21.

Mayer's course, Drama 51 - History of Film, is taught twice a week in two-hour sessions in 105 Dartmouth Hall. The room, which seats some 200 persons, was packed with an overflow crowd for his first lecture this spring. Enrollment is limited and many students, some of them sitting on the floor, were debating their chances of getting off the waiting list and into the class. Mayer lectures for the first hour of each session and the second hour is taken UP by screenings of "shorts" - Keystone Cops escapades, early animations, or clips from feature-length films - chosen as much for their entertainment as educational value. Sometimes Mayer is able to persuade critics, directors, screenwriters, and producers he knows to come up to Hanover to talk to the class. Students are also expected to attend two or three additional movies every week and to submit a number of reviews which are read and commented on by teams of graders who pass on to Mayer examples of the worst, best, and average writing. "I don't care what you say in your papers," Mayer tells his class, "or whether or not you agree with my evaluation of a particular film, just so long as you give reasons for your opinions." He encourages disagreement: "Speak up if you don't agree with what I say. After a lifetime spent in the motion picture industry, I'm not accustomed to excessive courtesy."

WHILE I was an undergraduate I never took Mayer's course, but everyone I knew who had taken it told me I should. I was afraid, every time I missed, that Mayer wouldn't make it back the next year to teach, so this year I jumped at the chance to sit in on his lectures. After all, I said to myself, he is over 90 and who knows if this year won't be his last? He is not at all the antique I expected; the legend is very actively alive. He was reportedly affronted, several years ago, when he happened to read a drama department memo concerning long-term curriculum planning which said, in part, "It can't be anticipated that Professor Mayer will be here forever."

He sits on a high stool behind a lectern to deliver his lectures. He has a strong, distinctive voice which sounds as if he grew up in New York, which he did. He is articulate - even eloquent - and speaks in complete, rotund sentences, often alliterative, which roll off his tongue one after the other. His lectures, read from notes but frequently straying afield, are actually witty monologues, sometimes genteel in their language and sometimes graphically explicit, particularly when he is quoting or impersonating such distinctive characters as Samuel Goldwyn, Adolph Zukor of Paramount, Mae West, Harry Cohn of Columbia pictures, or Keystone's Mack Sennett. A huckster for the movies, Mayer could easily have played the part of a barker in a circus film, but in class you have the feeling he isn't so much talking at you as taking you into his confidence. More than lectures, his orations are performances, events.

The quality of the performance is a serious concern of his. A New Yorker profile of Mayer tells how, when he once heard that a Dartmouth sophomore was entertaining friends with a successful impersonation of him, he begged the student for a private demonstration. Recognizing certain characteristic intonations and mannerisms in the takeoff, he signed up, at the age of 85, for voice lessons. "The only two stars who didn't take voice lessons when the talkies hit Hollywood," Mayer says, "were Emil Jannings and Rin Tin Tin; Jannings couldn't learn to speak understandable English anyway, even if he tried - he was born in Brooklyn."

Telling his class that he likes to visualize himself "as that great mentor, Mr. Chips," Mayer promises during his introductory lecture to present "the liveliest course in all of Dartmouth, the scandalous inside story of the movies, a course in sex education that will take us from Victorian virtue to violence and vice." His hope for the course, he stresses, is that it will enable his students to watch a film with some sort of appreciation for all the different talents that go into making it, and that students will come to understand how impossible it is to separate the artistic aims of films from the financial considerations that go into making them. "Motion pictures are the only art form that had purely commercial origins," he says. "The money-making inclination came first - the possibility of making a work of art came later. ... The first responsibility of the motion-picture writer, director, or producer is to attract people to the box office - but that doesn't mean that what is created is trivial." Mayer, who doesn't apologize for the money-making inclination of movie makers, quotes a former Columbia president as asserting, "Movies ain't no arty-farty bullshit. . . . They aren't even a goddamn industry." Although Mayer himself claims to have "an instinctive dread of the academic culture vultures, of which movies, because of their popular origins, have remained relatively free," he has done as much as anyone to legitimize the teaching of film in colleges.

In the New Yorker profile, Max Youngstein, former head of United Artists, said about Mayer:

In a business of highly specialized small minds, he was one of the rare individuals with an overall concept of how that business affected the cultural and political aspects of our lives. He filled an essential need, for which he has never been given enough credit: He served as a bridge between the recognition of creative talent and the making of money out of it. And this is what he's been bringing to young people through his teaching - a sense of what the industry is all about. That he should have been relegated only to teaching is one of the saddest and the dumbest things the industry has ever let happen. He should at least have been president of a big film company. But he was considered too intellectual, too witty, and people were suspicious of him. How could a man with a first-rate mind, they would wonder, be in the motion picture business to begin with?

After Mayer graduated from Harvard in 1907 (he delivered the student commencement address), he cast about for a job to support himself while laboring, unsuccessfully it turned out, at being a writer of novels. He attempted, also unsuccessfully, to corner the market on Panama hats and worked for a time as a mirror salesman. Having taken several art courses in college, he soon decided he was more suited to a career in an art gallery. Mayer called on a family friend, who was a banker, and confided he wanted to do something with pictures. His business advisor apparently misunderstood Mayer's interest in fine arts to be an interest in motion pictures, a new field with a profitable future. "By good fortune," Mayer says, "my friend's bank had only recently loaned a few million to a promising young picture maker, none other than a man named Sam Goldwyn, to whom he would gladly give me a letter of introduction. A few moments in Mr. Goldwyn's modernistic Fifth Avenue headquarters quickly disclosed to me that he was no dealer in the traditional arts." Mr. Goldwyn, whose name at the time was actually Goldfish and who had comedienne Mabel Normand on his lap, asked the 21-year-old Mayer, "Do you want to start today or wait until Monday?" Mayer started immediately.

The first movie Mayer saw was the first - or almost the first - showing of Mr. Edison's Kinetoscope at Koster & Bial's Music Hall on April 23, 1896, when he was ten years old. "I distinctly recall," Mayer Says, "that the female dancers in the picture were fully clothed - which even at that early age, came as something of a disappointment to me." A year or two later he went to the movies again, this time to one of the penny arcades which were flourishing in New York in the late 1890s. "If you dropped a penny into a slot, looked into an aperture and ground a crank, a light flashed on and for approximately half a minute you could watch a U.S. battleship at sea, Joe Jefferson as Rip Van Winkle, a ballet dancer, or a young girl, unhampered by excessive underwear, climbing an apple tree." Mayer claims he knows the opening- day receipts for the arcade featuring those attractions: the battleship grossed 32¢, Rip Van Winkle 49¢, the ballet dancer took in $1.12, and the girl climbing an apple tree was good for $7.18. "Sagely forecasting the future of the American film industry," Mayer says, "the proprietor concluded that 'we had better have some more pictures of the girl-up-a-tree variety.'"

Mayer's first year working for Goldwyn was spent selling movies to nickelodeons, along with such advertising accessories as posters, window cards, and illustrated slides which might read: "You Wouldn't Spit On The Floor At Home - Don't Do It Here" or "Kindly Read The Titles To Yourself - Loud Reading Annoys Your Neighbors." The title cards themselves were masterpieces of a sort. Example: "Passion, That Furious Task Master, Strikes Without Warning And Leaves The Mark Of Its Lash Across The Soul" Mayer remembers with particular fondness a caption which appeared below a shot of a film's brawny hero who was guiding a canoe down a raging torrent with one hand while he clasped the heroine to his side with the other: "Down The Virgin Falls."

Goldwyn next put Mayer to work auditing the receipts of his Chicago exhibitors. Mayer made the mistake of finding out that the branch manager was in cahoots with Al Capone and that the mob was lifting a hefty percentage of the profits. Someone saw a copy of the letter he wrote notifying Goldwyn of the swindle and, as Mayer says, "I had to be smuggled out of Chicago on a 3:00 a.m. milk train to avoid being encased in cement and sunk in Lake Michigan." Goldwyn mistook Mayer's naivete for courage and loyalty and rewarded him with the impossible job of auditing the affairs of the rest of his exhibitors.

Mayer frequently spices a lecture on the early days of the industry with Goldwynisms gleaned from his association with the mogul: He says he once heard Goldwyn say to an unhappy exhibitor, "A verbal contract isn't worth the paper it's written on." When an employee botched an important job, according to Mayer, Mr. Goldwyn snapped, "The next time I send a dumb sonofabitch to do something, I'll go myself." And on a later occasion, when the two were reminiscing, Goldwyn reflected, "We've passed a lot of water since those good old times."

Adolph Zukor, president of Paramount, gave Mayer his next job, this time writing publicity copy for the advertising department. "My job was to write a story every day," he says. "If nothing happened I had to make something up." Mayer was apparently so good at making things up that he became head of the department with responsibility for the publicity campaign for Mae West's first starring film, SheDone Him Wrong. Miss West was reputedly all-too-easy copy and Zukor, hoping to cash in on 'her reputation but also worried that nice people might be offended by overly suggestive advertising, warned Mayer to be careful. Mayer says he came up with a poster, "an admirable combination of zeal and caution," bearing a close-up photograph of West's bountiful bust and only one line of copy: "Hitting The High Spots Of Lusty Entertainment. When Zukor saw the poster he immediately objected to the use of a dirty word. When Mayer asked what word in the ad could possibly be construed as dirty. Zukor said "lusty." Mayer tried to explain the word's etymology and definition but Zukor cut him off: "When I look at that girl and see what she's got, I don't need none of your Harvard education to know what 'lusty' means."

It was a controversy over the campaign for another West picture, It Ain't No Sin, that finished Mayer's career at Paramount. He hit upon the idea of confining 50 parrots in a hotel room with a phonograph record which repeated over and over again, "It ain't no sin." The plan was to send the parrots out to theaters where they would be perched in the lobby to call out the title of the coming attraction. According to Mayer, even the least intelligent of the parrots had been almost completely trained when Zukor, attempting to appease the Legion of Decency, decided to change the film's title to I'm NoAngel. Mayer protested, refused to retrain the parrots, and the following day received a telegram from Zukor, whose office was just across the hall: "You are herewith discharged same to take effect immediately. Best regards. Remember me to Mrs. Mayer." Mayer had a contract with Paramount, however, and when Zukor was confronted with that fact he offered Mayer the Rialto Theater, located on the busy corner of Broadway and 42nd Street, in exchange for release from the contract. After some thought, Mayer accepted, only to find out Zukor had neglected to tell him the 2,000-seat theater was losing $2,000 a week. At that rate, Mayer figured, he had enough cash to stay open two weeks. He renamed the Times Square location "the double-crossroads of the world."

He took over management on March 4, 1933, the day F.D.R. closed the banks. A six-foot easel was put in front of the theater - anyone who lacked 25¢ for a ticket was promised admission in exchange for an IOU. Mayer estimates he gave out something on the order of 20,000 free admissions without ever being repayed a nickel. During the Depression the theater operated 24 hours a day, incidentally providing many men with a clean, safe place to sleep. Because the block-booking system, in effect until prohibited by the courts in the fifties, granted distributor-owned theaters a monopoly on the top pictures, independent exhibitors like Mayer only had access to B films or, as Mayer calls them, "the Ms - mystery, mayhem and murder." Labeled "the Merchant of Menace"' by the New York critics, he had his telephone operators answer calls by shouting, "Murder, rape, robbers, arson - help! . . . This is the Rialto Theater, what can we do for you?" Specializing in horror, he transformed the Rialto into a consistently profitable operation, screening such classics of the genre as Dracula,Wolfman, The Phantom of the Opera, TheMummy's Ghost, The Vampire, TheReturn of the Vampire, Frankenstein, TheBride of Frankenstein, The Ghost ofFrankenstein, The Cat People, and TheCurse of the Cat People.

MUCH of Mayer's success was due to his flair for publicity. When he advertised Paramount's Once in a BlueMoon as "The Worst Picture Ever Made," he broke the box-office record - and was sued by the picture company. "Thousands of people," he explains, "wanted to see how we could possibly play a worse picture than we ordinarily showed." In response to the slogan on Ziegfeld's marquee across the street, "Glorifying The American Girl," Mayer put up on his own marquee, in larger letters, "Glorifying The American Ghoul." He had a two-story-tall cutout constructed and placed on top of his marquee to advertise a gorilla movie. The monster carried a scantly clad, struggling blonde maiden in its arms and was wired for sound, emitting grunts and screams audible two blocks away while colored lights flashed on and off. The display was so effective that Mayer was served a summons for blocking Broadway traffic. When a critic for the New York Times reported the show outside was so much better than the one inside that no one went in to see the movie, Mayer made him a gift of the cutout and sent it over to the newspaper office, where it got stuck in the elevator.

Perhaps Mayer's greatest and most imaginative success at the Rialto was his 1938 promotion of a double-bill featuring Frankenstein and Dracula. He hired three ambulances to park in front of the theater, paid girls dressed as nurses to stand in the lobby and dispense pills, gave prizes to anyone attending three consecutive midnight shows, and arranged for people to faint during the show and then for ushers with stretchers to carry them out. Open day and night for a month and a half and charging 50¢ admission, the theater took in $40,000 a week. For $1,000 a week instead of the usual 25 per cent of box-office receipts, Mayer had rented the six-year-old films from Universal, which originally referred to his plan to double-feature them as "Mayer's folly." "Heaven forgive me," Mayer says, "I revived the popularity of double features for another 20 years." This year the Dartmouth Film Society screened the famous double bill in Mayer's honor, again to a full house.

What kind of people attended horror shows? The violinist Jascha Heifetz, for one, was a regular customer. Mayer traded him passes to the Rialto for tickets to his concerts at Carnegie Hall. Why did they like monster movies? "Perhaps," Mayer says, "because they were fed up with repulsive young women like Shirley Temple." When Mayer decided to sell the theater in 1948, bored with what had been for 15 years a very profitable enterprise, his announcement on the marquee - "Goodbye To Ghouls, Farewell To Horror" - was mistaken by faithful patrons for yet another twin thriller. A critic summarized the attractions Mayer offered as "no runs, no hits, just terrors."

Meanwhile Mayer had also been involved in movie production, but without the same consistent success he enjoyed as an exhibitor. He was the co-producer, in 1943, of a film made from a book, Education For Death, previously rejected by Warner Brothers. The title was changed to Hitler's Children, most of the $150,000 production expense was underwritten by Eastman Lab and RKO, and the advertising campaign, concocted by Mayer, featured a poster of a mostly naked young woman being flogged by a Nazi officer. "Our film rental amounted to over $4 million," says Mayer, "and rarely has devotion to the public welfare been rewarded so generously and so promptly this side of heaven. To clarify the record, I hasten to add that, overly impressed by our sagacity and showmanship, we invested all of our profits the following year in another similar but better picture, Behind The Rising Sun, an expose of Japanese jingoism - and promptly lost the entire amount." High Hell, a Mayer effort filmed in Switzerland and considered by some to be one of the all-time worst movies ever made, featured a supposedly nude leading lady, with obvious wrinkles in her body stocking, taking a bath in a barrel. Mayer did obtain some spectacular shots of blizzards taken on location on top of the Jungfrau, which were cut by editors in London who substituted cornflakes in the remaking of snow scenes.

Encouraged by the success of the talkies, Mayer flirted for a time with the smellies and produced, as he says, "what can genuinely be described as a complete stinker. Fortunately it was a short stinker." To supplement a scene of a couple amorously engaged in a meadow, Mayer pumped the odors of apples and burning leaves into the theater; for the wedding scene he added the fragrance of roses and too many people crowded together; the hospital scene was replete with the smell of soap and ether. There were difficulties. Mayer explains: "We blew the odors in at the right moment, but then we couldn't remove the smells and they all mingled together. You might think it was funny but it wasn't. It was as if a disgruntled patron had dropped a stinkbomb. Other theaters were able to make some refinements but no one showed a film which smelled as bad as mine."

As early as 1935, Mayer was importing foreign films, an endeavor that started when a man named Joseph Burstyn, a press agent for a Yiddish theater, burst into his office and offered him an alternative to the dismal standard fare at the Rialto. Burstyn, who had obtained the rights to a Russian film, wanted a partner with Mayer's experience in marketing. The partnership lasted until 1953, when Burstyn died on a trip to Europe. The two of them introduced the American public to films like Rossellini's Paisan and OpenCity, which Mayer smuggled out of Italy in a diplomatic pouch, Renoir's The LowerDepths, and De Sica's The Bicycle Thief. One Swiss film, The Eternal Mask, which according to Mayer "dealt with such intriguing, and then very novel, subjects as libidos, mother fixations, Oedipus complexes, and the like," arrived without its third and fourth reels. The partners showed it anyway and were surprised by the unanimously favorable reviews, one of which noted "the foreign flare for significant omission."

Mayer can also lay claim to a variety of off-Broadway accomplishments: At the beginning of World War II he was named deputy commissioner for the Red Cross in the Pacific and in 1944 was made a film consultant to Secretary of the Army Paterson. President Truman gave him the Medal of Merit in 1947, and the next year he became chief of the film division for the U.S. military government in Germany, where he was assigned to work under General Clay to re-establish and de-Nazify the German film industry. He was executive vice president of the Council of Motion Picture Organizations between 1950-1952 and was later president of the Independent Motion Picture Distributors of America.

MAYER says he likes teaching better than anything he's done before, although he dislikes grading. His course isn't all that easy - the writing requirements are stiff and the final exam presupposes a thorough reading of the text and regular attendance at lectures. He does have a habit, however, of repeating particularly pertinent facts with the admonition, "Write this down, it may very well appear on the final ... in fact, I can guarantee it will." He was distressed on one occasion when he thought he would have to flunk an obviously intelligent and capable student whose performance on the exam demonstrated only a hurried glance at a friend's notes and who failed to submit any written reviews. When he called the student in to his office to upbraid him for his inadequate performance, the student apologized and said his only excuse was that he had been completely occupied the entire term campaigning for Eugene McCarthy. "Just to show you I'm not an entirely honest character," he told the student, "I'll let you by with a C; if you'd been campaigning for Nixon you would have flunked." He thought he ought to clear his decision with an administrator and was further distressed when he was told that since it was only a course in film, and not in anything serious, he was justified in passing the student. On another occasion he proposed to his class at Stanford that in order to help the male students maintain their grades to qualify for draft exemptions, but at the same time keep the overall class average respectable, he might give all the men A's and all the women D's.

In Arthur and Lillie, a documentary film nominated for an Academy Award last year, Mayer insists he doesn't want to be "a lovable old man." Just the same, he and Lillie, his wife for 64 years, give students every possible chance to get acquainted. During his first lecture, Mayer announces his phone number and address and extends an open invitation for students to drop by and visit. Every other week the Mayer's hold an informal dinner for a dozen students and an assistant or two who take turns doing the cooking. "Let's talk about anything but movies," Mayer tells his guests, and he and Lillie carry on animated, informed, and demanding conversations about anything the students find of interest. Sooner or later the talk drifts back to films - Mayer estimates he's seen nearly 25,000 of them. He's opposed to censorship and the present rating system - "suitable for morons and children." Lilly boasts, "I'm probably the only woman in America who has taken her granddaughter to see Deep Throat - I laughed all the way through it."

When Mayer first came to teach at Dartmouth it was, he says, "a time of revolt and radicalism, and tremendous excitement. . . . The temper of the College has changed now and I think I like the rebellious students a little bit better than the ones now. I like them when they think things can be changed, when they still have ideals and think something can be done about the world." Has he ever thought of retiring? "I was planning to retire once; I was in my late seventies, I'd written one book and was planning to write another on foreign films, and we wanted some time to work on our farm - but then I started teaching. Sometimes I say this is the last year. When we don't feel so well we think we'll settle down, but Lillie says, 'Die with your boots on.' I like teaching. I like the kids and I think they like me."

Dan Nelson '75, an assistant editor of theALUMNI MAGAZINE, spent three nights aweek this spring going to movies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureYesterday's Glories Tomorrow's ?

June 1977 By JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

FeatureThey Also Went Forth

June 1977 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1977 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Valedictories

June 1977 By JOHN FINCH -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1977 -

Article

ArticleMr. Badger Makes the Boats Go

June 1977 By B.W.B.

DAN NELSON

-

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

MARCH 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureUncle Sam and Mother Dartmouth

November 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

OCT. 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFEBRUARY'S BIG EVENT: The Hopkins Dinner in New York City

January 1958 -

Feature

FeatureHas America Neglected Her Creative Minority?

December 1961 -

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

NOVEMBER 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Feature

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

MARCH • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Feature

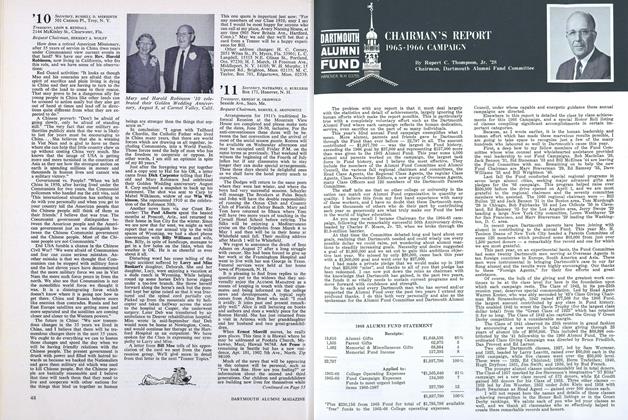

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1905-1966 CAMPAIGN

NOVEMBER 1966 By Rupert C. Thompson. Jr. '28 -

Feature

FeatureThe Singing of the Cider

OCT. 1977 By Sanborn Brown