A decade isn't a particularly long Aperiod of time. However, for Dartmouth athletics the years from 1968 until today represent a period of transition unmatched in any other equivalent span since the baseball team lost to Amherst, 40-10, in Dartmouth's first intercollegiate contest ever. That was in 1866. What follows are assorted reflections on the changing athletic scene from the time I arrived at Dartmouth in 1968 - just in time to chronicle the football team's first losing record in 13 years - to the present.

To say that athletics at Dartmouth have changed since 1968 is to badly understate the case. A program that provided intercollegiate competition for roughly 20 teams now fields more than 30 teams for both men and women. The participation factor - one in four Dartmouth students competes at the intercollegiate level and better than three of four are involved either in the intercollegiate, physical education or intramural programs - is firm measure of the role that athletics plays at Dartmouth.

The athletic plant has grown. The first significant change occurred 15 years ago with the completion of Leverone Field House, the facility that opened the way to renovations of Alumni Gym. (The Gym opened its doors in 1910 but today has come to the brink of being unable to satisfy the needs of 4,000 undergraduates, much less the rest of the College community.) Since the summer of '68, when Memorial Field was given new sod and 9,000 new seats, the most easily identified physical changes have included the improvement of Leverone Field House, by virtue of an all-purpose synthetic surface, and the completion of Thompson Arena. Pier Luigi Nervi's companion design to the field house ranks with the nation's finest ice and multi-use facilities.

Dartmouth's athletic program has grown because the College has grown. The development of women's athletics offered a massive opportunity for crisis, but the necessary changes were accomplished far more smoothly than many observers expected. In five years, this program has responded steadily to identified needs. The development of women's sports while attempting to maintain men's athletics on an established course clearly ranks as the finest achievement of Seaver Peters, who has been director of athletics since 1967.

THERE have been exciting moments in A every season of every year, far more than can be recounted sufficiently. However, permit a few recollections of the last decade that should stand alongside the most memorable from other eras.

The 1970 football season: The last of Bob Blackman's 16 years at Dartmouth was marked by a team that was as dominating as any the Ivy League had seen and probably ever will see again. Built around Jim Chasey, John Short, and Murry Bowden, it had awesome offensive ability matched with a defense that held six teams scoreless. On the final day of that perfect season, Penn was threatening to score in the final minutes. The ball was on Dartmouth's seven. Three plays later, Penn had been ejected beyond effective field goal range. The score was 28-0. It could as easily have been 82-0.

The 1971 football season: Blackman had gone to Illinois and many of the men who had contributed to 17 wins in 18 games in 1969-70 also had departed. Jake Crouthamel was in his first season, one to be remembered for Ted Perry's three game-winning field goals, including the last-second 46-yarder that beat Harvard, 16-13. Only a Perryesque last-minute Columbia field goal ended a 15-game winning streak and spoiled an otherwise perfect record in a season that was the third of five straight Ivy League championship campaigns.

The 1973 football season: Beaten in its first three games and written off, a great comeback (maybe the greatest?) of six straight wins was molded by a defense that stopped Harvard at the goal line three times in a gold-plated performance. That was the turning point in the season inspired by names like Tom Csatari, Herb Hopkins, Rick Klupchak, Rick Gerardi, Bob Funk, and Doug Lind.

Football hasn't been the only source of great moments, it's just the sport that gets the most attention. If the 1970 football season was a great one, so was the 1970 baseball season that saw the Green win 21 straight games and finish fifth in the College World Series. There was no moment more chilling than when Bruce Saylor cracked a two-run double off the fence at Rolfe Field to cap a four-run ninth inning rally that beat Navy, 9-8, and kept the streak alive. This team didn't win its share of the close ones: It won all of the close ones.

In basketball and hockey, remember these: Paul Erland's fallaway jump shot from the corner that beat Vanderbilt, 83-82, as the buzzer sounded nearly eight years ago. The James Brown-Billy Raynor-Paul Erland team that electrified Alumni Gym - and Harvard - on a December night in 1971. Fred Riggall's overtime wrist shot that beat Cornell, 3-2, at Davis Rink in 1972, a week after the Red had ripped the Green, 8-0. It was the turning point toward Dartmouth's first winning hockey season in seven years. Peter Proulx's goaltending that held off Harvard in a 4-3 win at Cambridge two weeks later. The third-period eruption that beat Cornell, 9-7, in the Thompson Arena dedication game last year, and Kevin Johnson's goal in the last second of regulation time against Brown in 1976.

And these: The duel between Chris Carstensen and Yale's Bob Kasting in the final leg of the freestyle relay in 1972. Carstensen, who had set meet records in two earlier races, touched out Kasting to give Dartmouth its first-ever win over Yale's swimmers. Ken Norman's New England-record run in the 600 against Brown in 1976. Take your pick of the Norman-anchored mile relay wins in 1975 and 1976. Keith Mierez's goal that turned back a tough Cornell soccer team on the road in 1974.

Depending on your interest and where you happened to be, there are a thousand more instances, equally special, in the annals of these years. There will be a thousand more in the next decade, just as there were in all the decades of athletics at Dartmouth. It's fundamental to the games that Dartmouth people play.

THERE has been, however, a fundamental change in athletics at Dartmouth and in the Ivy League, one that has altered the overall level of strength of Ivy teams in virtually every sport but especially in the high-visibility sports - football, basketball, hockey. Insofar as intra-league competition is concerned, the change has made things more interesting because there is a better balance of power than the Ivy League knew in its first 15 years of formal involvement.

The change has become conspicuous whenever Ivy League teams compete against non-Ivy opposition. Perhaps the only teams that have legitimate strength outside the league are Cornell's lacrosse team (national champions in 1976 and 1977) and Harvard's heavyweight crew. Princeton's basketball team is the only "high-visibility" team that comes close. With exceptions, the ability of teams throughout the Ivy League, including Dartmouth, to perform on an equal footing outside the league has deteriorated significantly.

The reason: money. Financial aid for college education. About six years ago, Tony Lupien, who concluded a 21-year term as Dartmouth's baseball coach this spring, predicted the socio-economic change that has become a fact of life in Ivy League athletics today. Given the cost of education at Dartmouth and virtually every other private college, and the fact that financial aid for everyone is awarded solely on the basis of need, the ability of the student (athlete or otherwise) from a middle class household to afford the Ivy League has become significantly more difficult. The time has come when the athlete with ability to compete at the major college level is logically going to need more than one good reason (education) to invest in the Ivy League. Over the years, it's the athlete from a middle-class background who has demonstrated the mental attitude that provides the ongoing nucleus of a competitive program.

The world of athletic recruitment has changed. Gary Walters, the basketball coach, has identified a growing number of high school student-athletes being accepted by Dartmouth and other Ivies but opting for a one-year investment in prep school in order to further refine athletic skills in hopes of being rewarded with a full, four-year scholarship somewhere outside the Ivy League in another year. The Ivy League's financial aid package - scholarship, subsidized loan, and employment - makes money, to many, a consideration as important as education. Maybe more so. As the cost increases, the overall quality of the athletic product decreases.

In terms of football among the Ivies, things also have changed. While Bob Blackman clearly ranks with the outstanding coaches in college football, he also was able to develop and capitalize on a recruiting effort during his years at Dartmouth that has since been copied by several other league members during the past seven years, most noticeably Brown, where one of his former Dartmouth assistants, John Anderson, is now the head coach. That same recruiting system, obviously, is being introduced by Blackman at Cornell this year, the institution Blackman long referred to as a "sleeping giant."

It's not that Dartmouth is recruiting less, it's that the rest of the league is recruiting more. While the Ivy League is built on a philosophy of common academic and athletic goals, it is apparent that some Ivy colleges have greater flexibility in admission standards than others, permitting the ability of some to work with a much broader pool of candidates with identified athletic potential.

In the national athletic marketplace, the Ivy League is a fading star. The great dilemma that is coming to pass is this: How to sustain an interesting, competitive, and nationally respected athletic program - particularly in the high-visibility sports but also in many other sports that these colleges offer to their undergraduates - in the face of a steadily constricting budget situation? This, be mindful, in the framework of the Agreement of 1954 in which the Ivy presidents directed that intercollegiate athletics be contested by players who are representative of the student body and "not composed of students offered admission or support by any different standards than apply to the rest of the student body."

Talk about coeducation, year-round operation, or any other reason, the ultimate fact is that athletics at Dartmouth and everywhere else in the Ivy League - and the league doesn't have an exclusive on the problem - is confronted with a financial dilemma of steadily increasing dimension.

The great strength of athletics at Dartmouth is its remarkably broad base of undergraduate participation. A dualism, however, is apparent in the desire to continue support of the expansive program that offers opportunity for everyone, regardless of skill, while at the same time providing those with greater skills the opportunity for competition at the level to which Dartmouth has aspired since the College began to play games.

At Dartmouth, athletics represents a significant part of life to all who share in the College community. What a tragedy it will be if the pressures of finance create an erosion of the intercollegiate program that continues to the point of embarrassment. Before that happens, commitments must be made at levels higher than those of the athletic administrators and coaches to determine if Dartmouth - and the Ivy League - will continue to compete in athletics at a level previously known or opt for a lesser plane.

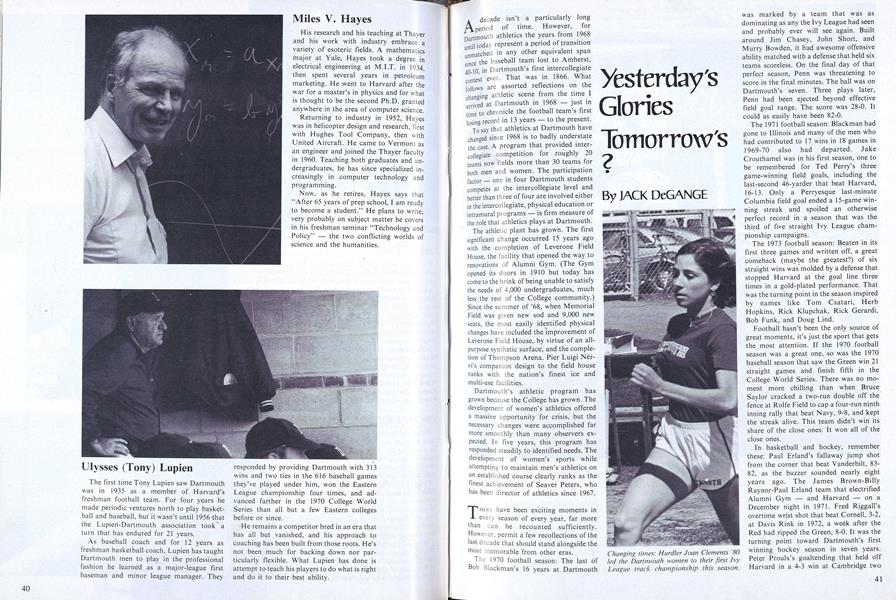

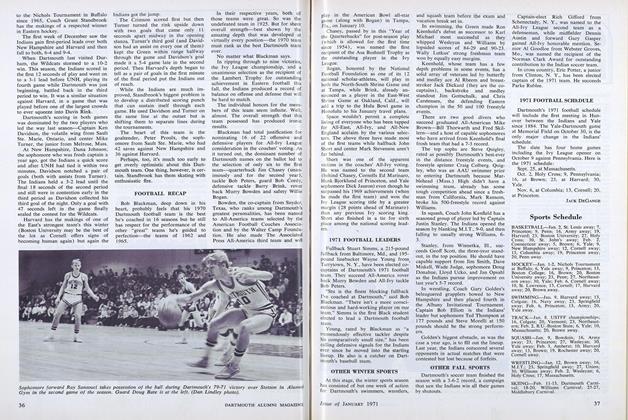

Changing times: Hurdler Joan Clements '80led the Dartmouth women to their first IvyLeague track championship this season.

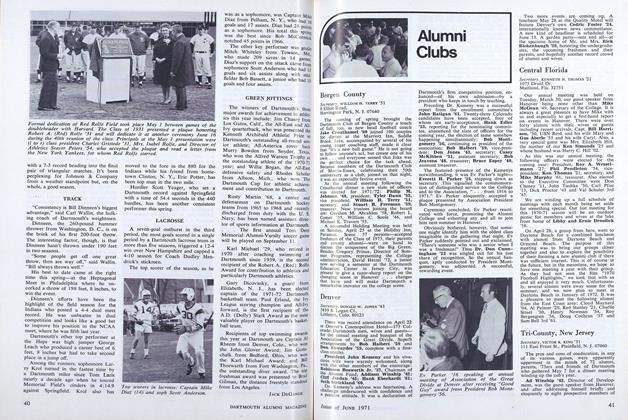

Old times: This fourth-quarter goal-line stand at Cornell in 1972 preserved a 31-22victory. It was the next-to-last step toward that year's Ivy League championship.

Old times: This fourth-quarter goal-line stand at Cornell in 1972 preserved a 31-22victory. It was the next-to-last step toward that year's Ivy League championship.

Jack DeGange will terminate nearly adecade as sports information director atDartmouth on June 30 to enter privatebusiness.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMerchant of Menace, Purveyor of Pleasure

June 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureThey Also Went Forth

June 1977 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1977 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Valedictories

June 1977 By JOHN FINCH -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1977 -

Article

ArticleMr. Badger Makes the Boats Go

June 1977 By B.W.B.

JACK DeGANGE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

FEBRUARY 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPipes's Cinch

MARCH 1995 By Al Henning '77 -

Feature

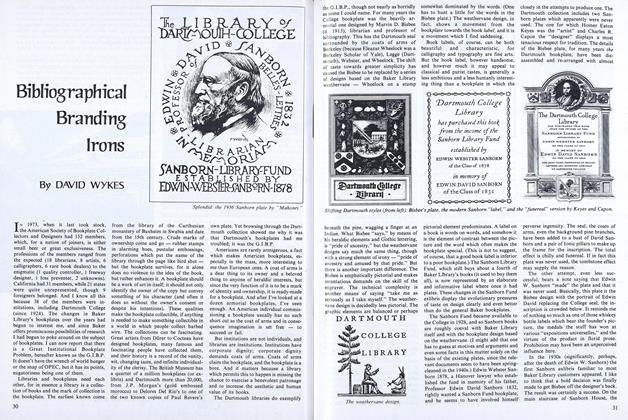

FeatureBibliographical Branding Irons

November 1976 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureIT'S GOOD

APRIL 1989 By Dinesh D'Souza '83 -

Feature

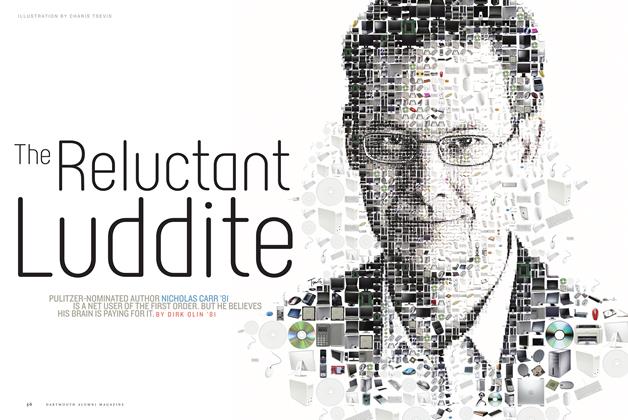

FeatureThe Reluctant Luddite

Sept/Oct 2011 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureSenior Valedictory

JULY 1972 By ROSS P. KINDERMANN '72