A year ago this fall a classmate and I embarked on a grand tour of the American West. In our minds we pictured our term-long expedition as an ultimate adventure during which we would experience many strange things, meet exciting people, and find out if California is really as weird as they say. When imagination finally became reality our expectations were more than met. The grandeur of the Rockies was incomparable, the depravity of Tiajuana extreme. We soaked our trail sores in a hot spring inside a cave and ate blue-corn tortillas in Santa Fe.

There was an additional element of the trip that went beyond experience. Traveling across the Midwest and criss-crossing the Far West was a completion of my firsthand view of the continental United States. To say I now "know" the country would be claiming too rhuch (I am from the South and am on good terms with the Northeast), but three months and 17,000 miles spent all over the West, particularly at colleges and universities, was enough for me to sense something of the thoughts of the people who live there. I was patticularly interested on our trip to test a thesis which had repeatedly suggested itself to me back east. This thesis, which was confirmed in the course of our travels, is that young adults in America today are verging on a loss of ethical values.

The new ethic that I see exerting its influence can be expressed as "Do what you can get away with." It is difficult to prove a broadly interpretive opinion such as this, for I have done no statistical research, no in-depth study. Nevertheless, the examples of this kind of immorality are rampant in my memory. Typically, I've experienced instances like the following, which occurred in Colorado: A friend wants to show me his new loft. The loft is, indeed, very nice. I ask him where he got the lumber. He replies that he procured it at one building site or another. The loft is made of long 2 x 4s, 4 x 4s, and a large piece of plywood. It is anything but scrap. I suggest to my friend that he has taken at least $30 worth of lumber. He replies that I'm right, but shouldn't be so moral. I began worrying about the implications of this kind of thinking when one day another friend, whom I respected, told me that if he was in politics he would accept a million-dollar bribe if it was ever offered for whatever reason. My friend figured anything less than a million dollars wouldn't be worth it. "I mean, you could go to jail," he said. What price morality?

Is this kind of experience becoming more frequent for the average young person, or are my perceptions those of a doomsayer? I can't say for sure, but there are reasons to suspect the former possibility. I have been struck in all the disturbing instances that come to mind by the approbation that was anticipated by whoever was relating the deed. It was almost as if they were recounting a victory of Us against some monolithic They. This suggests to me that the growing immorality of today is a reaction in part to a frighteningly complex world.

The Americans born in the last half of the 20th century have grown up in an environment where the only surety is that there's nothing to be sure of. They have seen the seemingly incorruptible edifice of federal government shown to be a facade. They do not know whether their accelerating technology will save them with the benefits of nuclear fusion and ever-better farming techniques or kill them with a fouled atmosphere and a nuclear holocaust.

Ironically, it is perhaps out of a sense of positive action that the decline I have postulated exists. In the sixties, the country experienced sweeping reforms in civil rights, government, and social attitudes that were largely initiated by the young. Central to these reforms was a new belief in the importance of the individual. Our country was founded on the rights of individual freedom, we heard, and the establishment was linked to repression, social conformity, and injustice. In part by emphasizing the role of the individual in the world, the rebellious young brought conscience back to our country. Paradoxically, this emphasis may have taken conscience away again as well. In the late sixties and early seventies the once-healthy trend toward individual responsibility in the world swung to the extreme of mere egoism. The watchword of the day became "Do your own thing," and the unspoken end to that sentence was "whatever that might be."

In the face of a frightening world it is easy to see how conscience turns into egoism and selfishness. The central idea of most moral theorists is that an action to be right must be acceptable to the actor whether he would be acting or be acted upon. In the words of the British moralist R. M. Hare, the action must be "universalizable." But central to an actor "universalizing" his actions to a group or anonymous other person is the actor's ability to identify with the group or the other person. The word we apply to everything besides ourselves is the world. If the world is as frightening and alienating as I believe it is, then it is almost inevitable that the young of today have trouble "universalizing" and are consequently increasingly immoral.

Naturally, the processes and problems I'm hypothesizing are not unbridled. The world has not disintegrated into anarchy, and neither is selfishness the general order of the day. The theft of $30 worth of lumber is not going to topple our civilization, but I can't help worrying when I detect more and more such incidents every year. It's the change that bothers me.

At Dartmouth specifically, the picture is neither all rosy nor all black. On the one hand, I know of one fraternity having a "SWAT team" that larcenously procures whatever the house needs. They seem amazed and uncomprehending when I ask them for a justification of their actions. (Incidentally, it is not my intention here to criticize fraternities. On balance, I think the fraternity system is one of the more positive aspects of Dartmouth). In a more encouraging light, I think we have an academic honor system that truly works.

What can be done to stem the degenerative tide if it exists as I say it does? At the risk of sounding sanctimonious, I believe we need an increased willingness of people to speak out for what they know is right. Along with a decline in values has come a decline in courage. Perhaps both trends can be reversed before it is too late.

Bill Conway, an English major, is one ofthis year's undergraduate editors andCampbell Interns. From New Orleans, hespent the summer working in theWashington office of Louisiana SenatorBennett Johnston.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

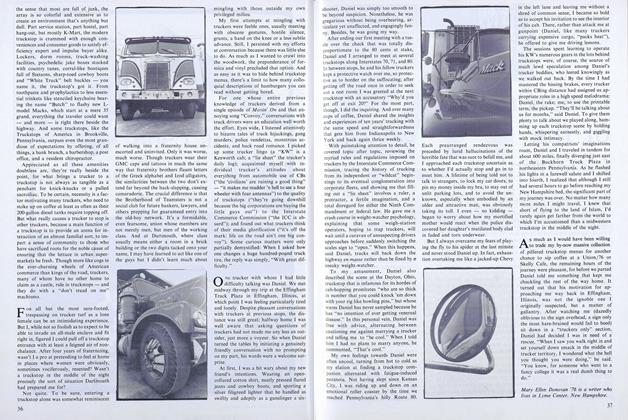

FeatureThe Lady and the Truckers

October 1978 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureBeauty and the Beasts

October 1978 By William Morgan -

Feature

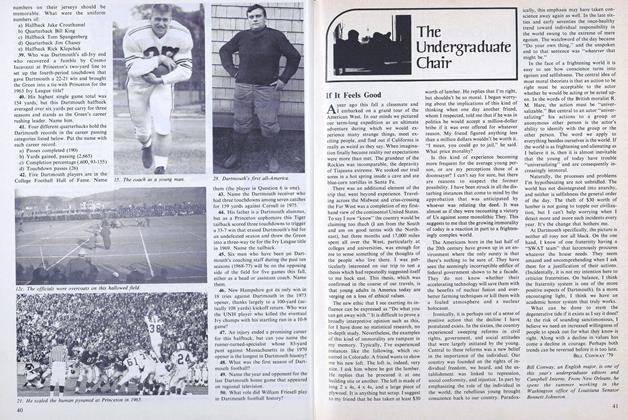

FeatureConundrum of the Gridiron

October 1978 By Jack DeGange -

Feature

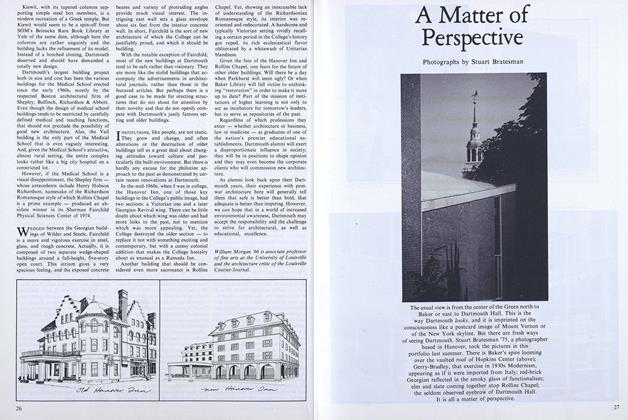

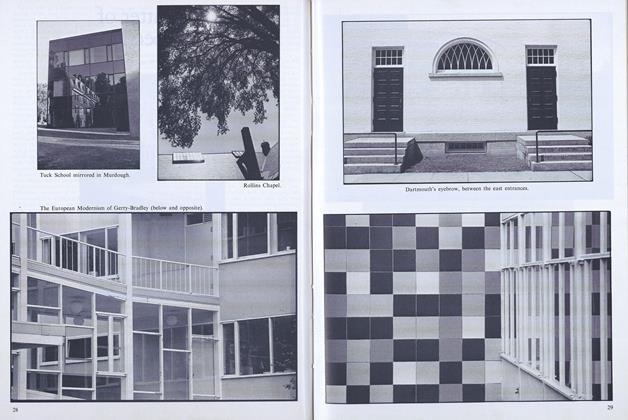

FeatureA Matter of Perspective

October 1978 -

Article

ArticleSignal-Caller for the Hurt

October 1978 By D.M.N. -

Article

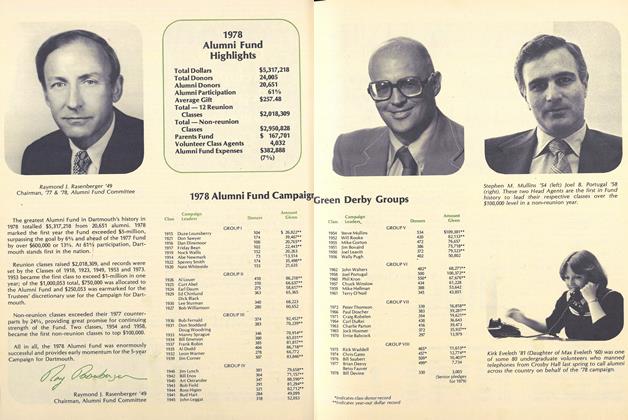

ArticleOffice of Development Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1978

BILL CONWAY '79

Article

-

Article

ArticleFor its highly significant archaeological frontispiece, THE MAGAZINE is indebted

-

Article

ArticleREADJUSTING THE COLLEGES

December 1916 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

SEPTEMBER 1997 -

Article

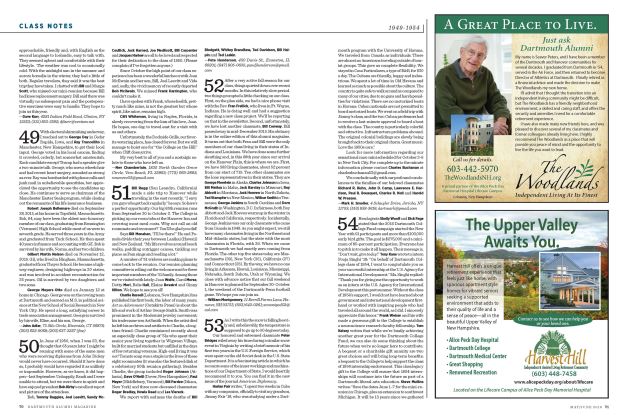

Article1953

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Mark H. Smoller -

Article

ArticleGOLF

JUNE 1970 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleOxford Revisited

MAY 1968 By JOHN G. GARRARD