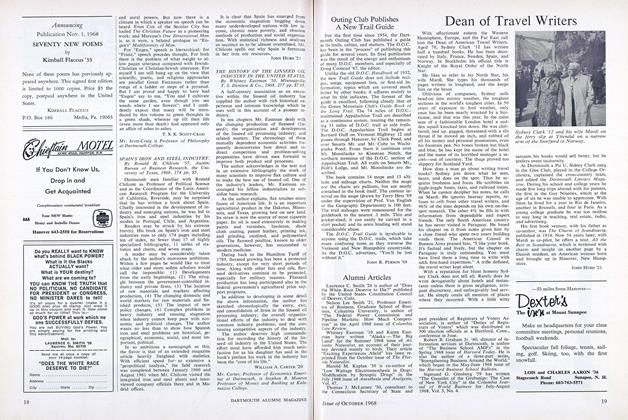

The New Black Eagle Jazz Band came to Hanover recently to play a benefit concert in Webster Hall for the Montshire Museum of Science. For two of the musicians, Peter Bullis '54, manager and banjo player, and Bob Pilsbury '48, piano, the engagement was a homecoming. Pilsbury first played on the Webster stage in 1944 with a group called The Four Brothers and also played lead saxophone for the Barbary Coast, a student band that is still active. Pilsbury is credited with organizing the once-popular Saturday Morning Concerts. "During the late forties and early fifties," he says, "you could find a dozen jazz bands playing at fraternities on any big weekend." One Saturday morning during Winter Carnival he managed to get every band on campus into Webster Hall for an impromptu jam session. Students were delighted and it became a tradition for six to ten local and student bands to perform every week.

Bullis played with the Dartmouth Indian Chiefs, a group which recorded an album, "Chiefly Jazz," and performed at Carnegie Hall and Boston's Symphony Hall. He credits his interest in jazz to the influence of a roommate, George Morris '54. "George had some records I didn't really like," Bullis recalls, "but I went home with him to New Orleans one summer and saw the bands the music was coming from. I was bitten by the music and bitten for good. 'What's the quickest and easiest way to play this music?' I asked myself. 'Banjo! I'm going to get one of those things and learn.' " Pilsbury came to jazz from what was pop music in the forties. He was also influenced by Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Fats Waller, and Joe Sullivan. "My father, Elmer Pilsbury '19, was one of my greatest influences," Pilsbury says. "Although he didn't know it, he really played jazz piano because he improvised."

After service in Korea and graduation from Dartmouth, Pilsbury went on to the New England Conservatory of Music and Boston University, taught school, spent a number of years as a professional musician in New York and Boston, attended graduate school at Harvard, and is now a practicing psychologist. Bullis graduated from Harvard's graduate school of design, went to Germany as a Fulbright scholar to study church architecture, and is now a partner in a Boston architectural firm.

All the members of the New Black Eagle Jazz Band lead full-time professional lives in addition to their nearly full-time work as musicians. The band, which has been together for six years and has a repertoire of some 400 tunes, plays every Thursday evening from eight until midnight at the Stickey Wicket Pub in Hopkinton, Mass. They play, in addition, over 120 outside engagements a year and frequently appear at jazz festivals in places like California, St. Louis, New Orleans, and Breda, Holland, where they were billed as the feature attraction of what is the major traditional jazz festival on the Continent.

They don't like to think of themselves as businessmen, doctors, or academics who also happen to play jazz; they prefer to be judged as musicians. The critical judgment has been unanmously enthusiastic: High Fidelity selected their album "Kid Thomas and The New Black Eagle Jazz Band" (one of six they've released) as one of the "Best of the Pops" for 1976 and said, "They are so far ahead of most of the other traditional bands in the country that there is scarcely any basis for comparison." Another reviewer exclaimed, "In the truest meaning of the word, this is a classic jazzband - hot, thoughtful, exciting, and - well - 'abounding in hot grace.' . . . The Black Eagles may be indeed the best classic jazzband to surface since Muggsy Spanier's Ragtimers in 1929 - and quite possibly, next to Spanier, the greatest white jazzband of all time."

Bullis says the band has considered the possibility of playing full-time. "If it could be shown it would work out economically, and if the jazz revival became a big thing, we'd think about trying it for a couple of years. However, the present combination of having two professions is marvelous. And there's always the question, although I really don't think it's valid, of if our music would suffer if we went commercial." According to Pilsbury, some of the reasons for the band's success are "having seven excellent musicians dedicated to the music, being in the right place at the right time, and having an excellent business manager in Bullis."

Their rousing, two-hour Webster Hall performance more than fulfilled the promise of their records. It featured arrangements of Duke Ellington's "The Mooche," Louis Armstrong's "Oriental Strut," King Oliver's "Shake it and Break It," Morton's "Jelly Roll Blues," and Scott Joplin's "Sensation." The band came ac- coutered with records and Black Eagle T-shirts for sale, bumper stickers, and picture post cards. "The only thing we didn't bring," said one member, "is autographed underwear." Their music can't be easily classified - it hails from New Orleans, but it's also a Chicago sound. They play fast and loud, but they're also precise and restrained. When pressed, Bullis calls the sound "classic, traditional, old-style jazz." Pilsbury claims that "It's more in the way we approach the music. We aren't trying to recreate the exact sounds of the old-timers. We look back to them, but our style is our style."

The highest compliment the band has received, Bullis says, was when they played in New Orleans and the first-generation black jazzmen came to hear them - and expressed approval. Pilsbury recalls another compliment, when their record was on the Best of Pops chart with records by Count Basie and Duke Ellington, and his son told him, "Dad, you're up there with Peter Frampton!" - a teen-age rock idol.

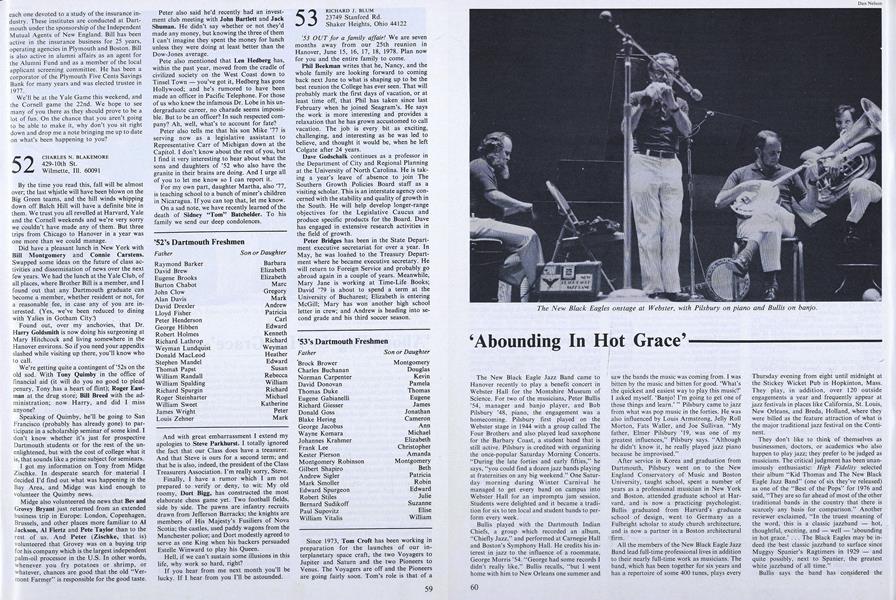

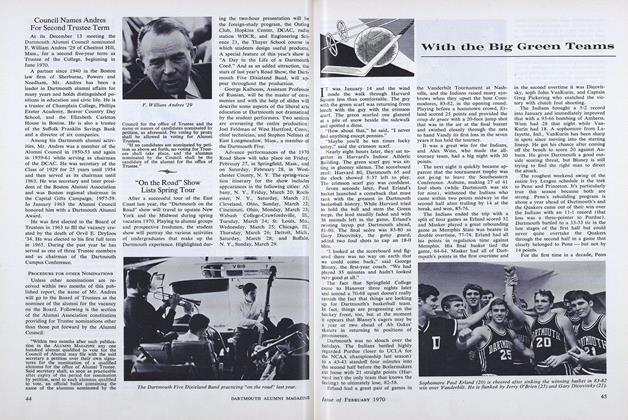

The New Black Eagles onstage at Webster, with Pilsbury on piano and Bullis on banjo.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFie on the Flush Toilet

November | December 1977 By Harold H. Leich -

Feature

FeatureSee How They Run

November | December 1977 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

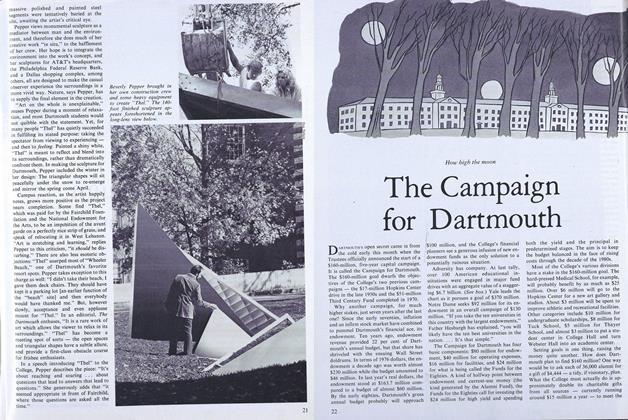

FeatureThe Campaign for Dartmouth

November | December 1977 -

Article

ArticleThe DCMB Double-entendre March

November | December 1977 By Anne Bagamery -

Article

ArticleDick's House Is Her House

November | December 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleTheir Fathers' Sons

November | December 1977

D.M.N.

-

Article

ArticleWorking with the Grain: Weed's Way with Students and Wood

December 1976 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleStepping Out with a Bounder

February 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticlePaddler, Climber, 4-term Planner

May 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

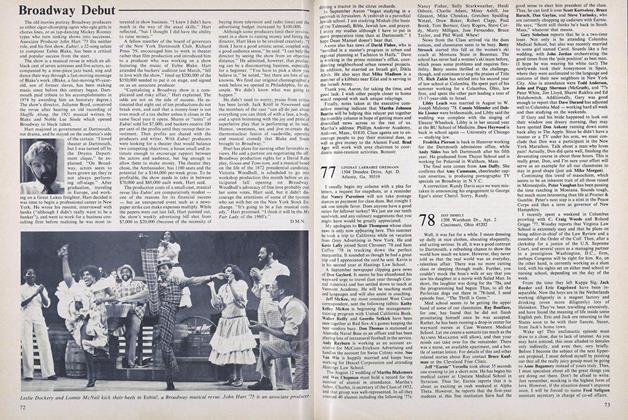

ArticleBroadway Debut

JAN./FEB. 1979 By D.M.N. -

Article

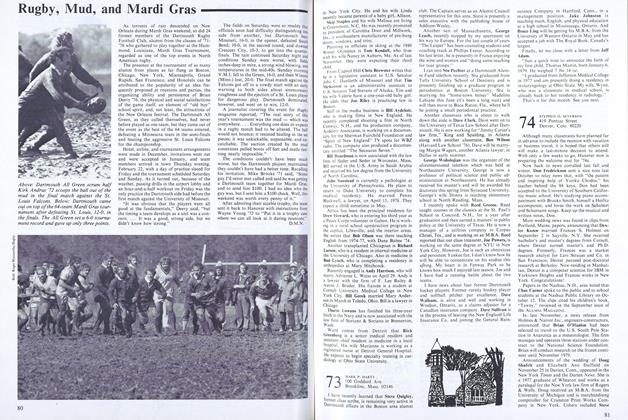

ArticleRugby, Mud, and Mardi Gras

May 1979 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleCombating the Crippler

September 1980 By D.M.N.

Article

-

Article

ArticleDR. J. M. GILE MADE LIFE MEMBER TRUSTEE

February, 1923 -

Article

ArticleClass and Club Officers Meet

June 1954 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

OCTOBER 1968 -

Article

ArticleCouncil Names Andres For Second Trustee Term

FEBRUARY 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1949 By Robert L. Allcott '50.