It was 15 years ago when Martin Anderson's first major book, The Federal Bulldozer, staggered the planning profession by attacking the urban renewal program as a "thundering failure." Once the furor had subsided, subsequent events verified many of Anderson's criticisms, particularly his assertion that renewal was carried out at the cost of displacing the urban poor.

Now Anderson has tackled an even more complicated area of public policy — welfare reform. Based on his experiences as an adviser to Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Ronald Reagan, he sets forth seven, often startling, major theses beginning with the assertion that "the 'war on poverty' that began in 1964 has been won." Citing a "little-known study" by University of Virginia economist Edgar Browning, Anderson concludes that "official statistics of the Bureau of the Census are wildly inaccurate and grossly overstate the amount of poverty in the United States." He then goes on to reject any type of "radical welfare reform" based on the concept of a guaranteed annual income as advocated by Presidents Nixon and Carter, and such other assorted individuals as. Robert Theobald, Patrick Moynihan, or even Milton Friedman (in the form of a negative income tax).

Hence, Martin Anderson appears, once again, as the provocative gadfly who performs the very useful role of challenging prevailing assumptions and raising difficult questions. His book is extremely well organized, clearly written, and exceedingly stimulating. In the end, however, I found his case against a guaranteed income approach less convincing than his earlier dissection of the urban renewal program.

In his second major thesis, for example, Anderson indicates that the poor presently have no reason to work under the existing welfare system because eligibility requirements create "a 'poverty wall' that destroys the financial incentive to work for millions ... of ... dependent Americans." Two chapters later, however, his major criticism of a guaranteed income approach is that it will cause "a substantial reduction — perhaps as much as 50 percent — in the work effort of low-income workers." How does he attempt to reconcile these potentially contradictory observations?

Anderson believes that we should rely less on work incentives which attempt to persuade people to work and more on stricter enforcement measures which require people to work "if a person is capable of taking care of himself." In other words, he is calling for the kind of tougher, tighter, and more efficient administration of the present welfare system, which has an attractive political appeal. This is fine in theory, but does it mean adding still more enforcement personnel to an already swollen welfare bureaucracy to ferret out potential abuses? And is it really as easy as Anderson implies to classify "those who can't help themselves" through the imposition of ever more stringent welfare regulations? Anderson doesn't really attempt to answer these types of questions except for an oblique reference to Governor Reagan's 1971 California program as "the most dramatic example of practical welfare reform ... that actually worked."

Perhaps. But frankly I'm skeptical about whether the types of administrative reforms Anderson proposes will resolve our increasingly intractable welfare problems. He concludes that we can tighten up our present system and make it work. I'm not so sure. Yet, in the final analysis, I have to admit that Anderson was well ahead of most observers in analyzing the urban renewal program 15 years ago, and it's always possible that he may have managed again to see some light at the end of the existing welfare tunnel that has escaped many of the rest of us.

WELFAREBy Martin Anderson '57Hoover Institution, 1978. 251 pp. $10

Frank Smallwood is Orvil Dryfoos Professor ofPublic Affairs and chairman of the PolicyStudies Program at the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureJazz Comes to College

November 1978 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

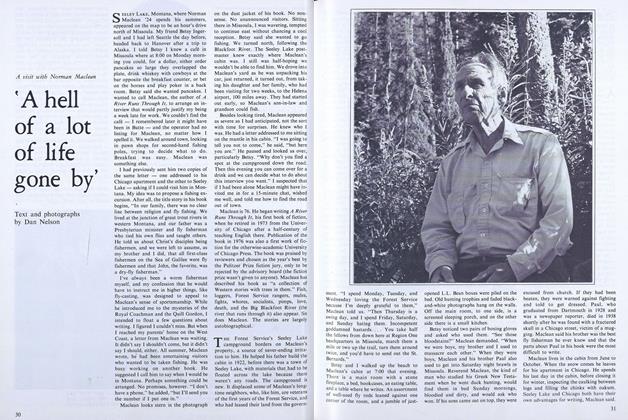

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

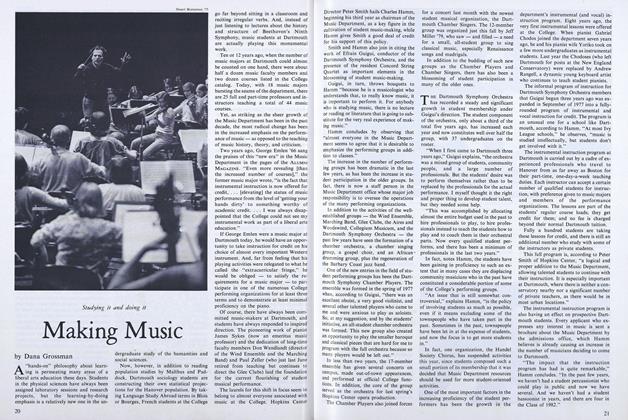

FeatureMaking Music

November 1978 By Dana Grossman -

Article

ArticleThe Joy of Moving

November 1978 By W.B.C. -

Article

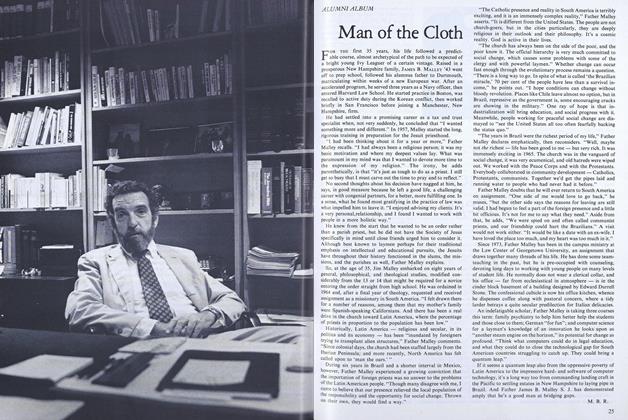

ArticleMan of the Cloth

November 1978 By M.B.R.

FRANK SMALLWOOD '51

-

Feature

FeatureThe TPC Planning Program

April 1960 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

Books1600 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE.

July 1960 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksTHE MAKING OF URBAN AMERICA

JULY 1965 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksNEIGHBORHOOD GROUPS AND URBAN RENEWAL.

JULY 1966 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksTHE ZONING GAME: MUNICIPAL PRACTICES AND POLICIES.

FEBRUARY 1967 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Feature

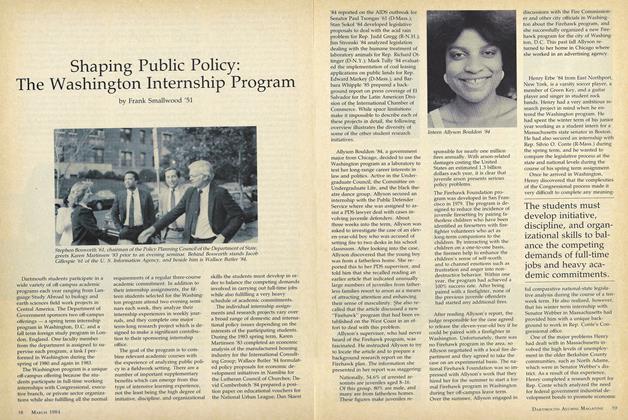

FeatureShaping Public Policy: The Washington Internship Program

MARCH 1984 By Frank Smallwood '51

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

JANUARY 1966 -

Books

BooksTHE VALUE ISSUE OF BUSINESS.

JUNE 1967 By JAMES BRIAN QUINN -

Books

BooksThe Birth of a Nation

APRIL 1984 By Jean Kemeny '53ad. -

Books

BooksON THE STAKED PLAIN

June 1940 By Mabel L. Seavey -

Books

BooksHORTON HEARS A WHO!

December 1954 By MAUDE D. FRENCH -

Books

BooksTears and Tinkhamtown

November 1975 By NELSON BRYANT '46