WHEN the Reverend Samuel Colcord Bartlett intoned those sobering words to his scurrilous young charges amassed in chapel around 1880, he laid his finger on — or rather lashed his tongue at — an annoyingly recurrent issue facing the College or any educational institution: the problem of student conduct and discipline. All too often over the last 208 years, that voice crying in the wilderness has had to concern itself less with education and more with reprehension. As the students have run amuck, the administration has been called on to expend disproportionate amounts of time and energy to bring them to account, dispense appropriate penalties, and restore the general decorum.

Recently, the fraternity system has been the center of the discipline debate, standing accused of promoting behavior not unlike that President Bartlett attributed to his simian friends. Again and again, the question has arisen of individual responsibility, or just who is accountable for what. The answers are a little more difficult to come by, but a glance at the past may offer a new perspective. Discipline — and the need for it — at Dartmouth is as old as the College. The contrast between the early days of presidential dictatorship and the present system of well-defined "due process" can be instructive.

Leon Burr Richardson, in his History ofDartmouth College, indicates that in the first years, the Rev. Dr. Wheelock allowed little nonsense in his new school. Students were expected to follow a strict schedule of chapel, recitation, study, meals, and prayers, leaving little opportunity for dubious leisure-time pursuits. Naturally enough, rebellion frequently erupted. On one such occasion, in 1774, the students took advantage of the President's absence to institute a period of bacchanalian revelry, entrenched within Payne's Tavern. Upon Wheelock's return, six young gentlemen found themselves no longer associated with the College, victims of a righteous wrath.

It was not until 1782 that the first definite code of laws was drawn up — the ancestor of pages 42-45 of the present-day student handbook. At that time, the crimes of "treason, forgery, blasphemy, perjury, and open and gross lewdness" demanded the ultimate penalty of separation. (These days, transgressions number 2 and 4 can lead to the same end.) Lesser punishment was inflicted for lesser offenses, including drunkenness, riotous behavior, and "disorderly night walking."

Then as now, infractions were usually confined to the minor league. For instance, the finer specimens of village poultry had a disturbing tendency to turn up roasting over dorm-room spits. "Misappropriation of College property" was a problem past and present, with one stuffed zebra in particular acquiring the habit of appearing in "incongruous places." But in'the area of vandalism, modern efforts sometimes seem slight by comparison. On two occasions, a cannon appeared at the center of the festivities, once being used to gain entry to the old "College" by merely blowing off the door, and once discharged beneath the window of an unpopular faculty member, taking a toll of some 300 panes of glass. A somewhat more startling episode occurred in 1789, when the students, frustrated by building delays in the new Dartmouth Hall, provided an incentive to complete construction by attacking and leveling the old structure in one evening. Occasionally, the sporadic violence took on a nastier form, as during Commencement in 1824 when a local store employee wrote to his brother: "Already have the students burnt one barn, stoned Prof. Chamberlain, burnt him and tutor Perley, and hung the President in effigy.... "

At first, the President himself was police force, judge, and jury. Thus, the full weight of the executive authority often descended upon unwitting students in the form of an enraged Eleazar Wheelock, weeding out the lawless by kicking in the doors of locked "dens of iniquity." Though less directly involved, later presidents such as Nathan Lord continued to administer personally to the wicked through interrogation and exhortation. Dr. Alpheus Crosby noted in 1853: "No victim of the Inquisition ever dreaded the thumbscrew or the rack more than the college malefactor feared this scathing interview with Dr. Lord."

But on the whole, disciplinary authority resided in the faculty itself. Aside from addressing College business and curricular concerns, the full teaching body also sat in judgment on all questions of conduct and punishment, which often included assigning a student to an individual professor for "conversation, advice and reproof." It was not until 1893 that some of the authority was delegated to a Committee on Discipline, and not until 1906 that the group, renamed the Committee on Administration, was empowered to act with finality in all cases of discipline, for breaches of both conduct and academic rules.

Since the larger body gave up its rights only reluctantly, it is no surprise that undergraduate clamor for a voice in such matters was largely ignored. Though the editors of The Dartmouth called for student involvement in discipline as early as the 1880s, the desired reform did not arrive until after World War II with the establishment of the Undergraduate Council. As it was originally conceived, the UGC Judiciary Committee was to have conducted preliminary investigations and hearings on conduct cases, referring its recommendations to the faculty committee for a final decision. But the ideal was not always the rule.

Thaddeus Seymour, dean of the College from 1959 to 1969, remembers that the UGC-JC "got to be somewhat political, almost to the point of plea-bargaining. They were trying to second-guess and figure out what was expected of them." Communication between the two groups was something less than candid, and additional strain came about whenever the faculty overrode student suggestions. It also became generally recognized that students should have a role in decisions on "standing" as well, on matters such as academic sanctions and grade-change requests. To help solve these problems, Seymour organized in 1967 a group entitled, appropriately enough, the College Committee on Standing and Conduct.

The same body exists today, in more or less the same form, consisting of Dean of Students John Hanson '59, four faculty members, four elected students, Dean of Freshmen Karen Blank as head, and Assistant Dean Ann Craig as non-voting secretary. Concerning standing, the committee determines academic sanctions ranging from permanent expulsion down to simple warnings, and deliberates on a number of routine requests for late registration, course-drop deadline exceptions, and so on. Concerning conduct, it passes out penalties for student mischief, as well as deciding on honor principle violations. All totaled, the CCSC took over a thousand individual actions last year alone. Not surprisingly, the Wednesday afternoon meetings sometimes drag on past midnight.

The committee refers to a session on a conduct violation as a "hearing" - just a little informal information gathering. From the other side of the table, the ordeal may appear somewhat more traumatic. For a hypothetical example, consider a student up on the most common charge, "misappropriation of College property." Ripping off a dorm couch it's called in the vernacular. (Two other major problems are vandalism and drunk-and-disorderly conduct.) Since courts in recent years have been willing to step in where a student has been denied a "due process" examination, the College takes extra precautions to make sure an individual knows exactly what is happening and when, both to insure fairness and to protect the school. So, before he gets to the CCSC, our alleged thief will usually have been "invited" to a couple of other meetings: one with the College proctor to retrieve his I.D. confiscated by the Campus Police officer who thought the couch should remain where it was; and one with Assistant Dean James Bryan, who investigates the incident a little, explains to the student his rights, and sets an appearance date at least five days in advance.

The Wednesday hearing can be open or closed, the proceedings can be taped, and the student has the right to an "adviser" in addition to necessary witnesses. Though some students opt for legal counsel, the CCSC prefers the less formal route of a faculty member or administrator, hoping to avoid a courtroom atmosphere. Bryan especially worries about gaining a "prosecuting attorney" image, since it's his duty to present the charges at the hearing and remain to clarify the administration's viewpoint. At the hearing itself, the student makes an opening and closing statement, with questions from the committee in between.

If the final decision is "guilty," the punishment options open to the CCSC are everything from a slap-on-the-wrist letter of reprimand up through suspension and, in extreme cases, expulsion. Though committee members are reluctant to judge a case out of context, our first time couchthief would probably not be suspended, but repeated offenses are viewed differently. Also, the student is warned beforehand in writing: "Lying before the committee may lead to separation." After the verdict, one last appeal for clemency can be made to the dean of the College.

What may be disturbing to some and comforting to others is that despite this formalized structure of interviews, hearings, and appeals, a student's fate hinges on human factors all down the line, perhaps as much as it did in Eleazar's day. An objective set of laws exists, of course, but how they are "applied and the penalty for violating them are subjective determinations of individuals. On the positive side, the system remains responsive to individual needs and extenuating circumstances. On the negative side, the rules can be enforced arbitrarily or punishment handed down unevenly.

For example, whether or not a student begins this disciplinary odyssey at all often depends on a late-shift Campus Police officer. As one ex-dean put it, "The CCSC applies only where someone is A) caught, and B) caught and written up." Although the cop is naturally expected to take an I.D. in serious matters, he has to rely on his own quick judgment while approaching, say, a sizable group of misappropriators or a merry band of vandals. Who receives what can be as arbitrary as who gets grabbed first, or the difference between a long hassle and an amicable agreement can be how the cop feels, how the student behaves, and how the two mix. In fact, any tense situation can be defused or ignited, depending on the way the officer handles it.

In his days as a patrolman, the current proctor, Robert McEwen, had a disconcerting habit of memorizing ; most of the faces from each year's freshman book. "You'd be surprised," he says, "how tame students will get when you walk into a crowd that's never seen you before and start greeting everyone by name." Such tactics are most effective before anything explodes, and McEwen tells another story of preventive medicine involving his predecessor, the late John O'Connor: once, a small but destructive band of fraternity brothers, indignant that one of their group should have been forcefully detained behind bars by the town police, had set off down Main Street to free their comrade and perhaps rearrange the cell block. Receiving a phoned-in tip, O'Connor headed them off at the pass, threw the proposal open for discussion, and prevailed with the light of reason, thereby preventing Hanover's first prison riot.

But assuming conciliatory measures fail, I.D.s are snatched, and reports are filed, the next step is for the proctor or lieutenant to determine if the incident should be referred to Dean Bryan for CCSC action. The key factor is usually personal injury: Shooting a bottle rocket out a window costs a student $25, while shooting it onto someone's head warrants higher action; a waterfight is not too serious, but a water-fight plus a broken arm is. The deans also make similar decisions, sometimes themselves handling cases such as interstudent disputes. And once a violation finally arrives before the CCSC, a number of other variables come into play: the opinions, emotions, and prejudices of those making up the committee that term; the atmosphere prevailing at the College; or the context in which the offense occurred.

Given such a potential for use or misuse of human judgment, it is not surprising that definitions of what behavior deserves what and the administration of discipline as a whole can change as those humans change. It is a popular conception among undergraduates on campus that a late sixties trend toward a liberalized view of stu- dent behavior has taken a swing back in the other direction during the last few years. This belief usually crystalizes into a criticism of the current dean of the College, Ralph Manuel '58, as too "authoritarian" as compared with his predecessor, Carroll Brewster. Of course, whether or not this overall perception is accurate depends on whom you ask.

Proctor McEwen, for example, is often confronted with such questions. "Alumni come up to me and ask, 'What's this major crackdown I hear about?' which makes me feel great - just like I've been nominated to a vice squad somewhere." McEwen is always careful in his response, usually pointing out a "drastic change in attitude" among students over the last five years, individuals are less patient with having their rights infringed upon and more demanding that others take some personal responsibility. More calls to the police reporting obnoxious inebriety or vandalous behavior means more cases before the CCSC. Nevertheless, when pressed, McEwen cautiously admits his own impression of a discipline shift with each succeeding dean: "I think in the late sixties, certain issues moved to the forefront, like Vietnam and the drug culture. Other issues like student behavior, drinking, and rowdyism moved to the background. Around '73 or '74, we began recognizing the problem we did have, and a tightening-up of things began."

Thaddeus Seymour, the dean when McEwen arrived 11 years ago, can speak with authority on the situation in the sixties. Seymour characterizes that decade as a constant trend toward a liberalization of the rules. "I was always on the side of having faith in reasonable people to behave reasonably. So rules like no drinking after 1:00 and room parietals gradually fell away." This growing freedom was intertwined with a change in how the College currently viewed itself and others. "Just for instance," Seymour adds, slipping into a less serious mode, "I remember in the early sixties the 'drop-trou' problem caused big concern. Also, we had a furor over shouting obscenities on the Smith campus. Well, times change. Seven or eight years later, streaking makes the other problem seem tame, and I doubt anyone would even bother to report obscenities these days."

Another shift occurred in the disciplinary measures themselves. By the end of the sixties, a College reprimand or probation had lost most of its punitive value. Suspension became practically the only punishment of any impact. Thus, while the effort going into discipline decisions increased, the number of really decisive actions decreased, with only three conduct-related suspensions last year. In Seymour's words, "One of the biggest dilemmas for me was going from Dartmouth, where all this took a great deal of time and psychic energy, to a small college in Indiana where we had no committees. As heretical as it sounds, I've found the rule of the dean has the great benefit of saving thousands of hours, with the results not coming out that different. If the saved time goes into academic endeavors, that's progress; if it's wasted, you're no better."

Carroll Brewster, Seymour's successor, also laments the lost time. But his current attitude toward discipline might surprise those who remember him as "Brew Deanster down on the row with the bro'." He says: "My feeling was that keeping the lid on undergraduate rowdiness was a strenuous occupation for the dean. We had to make everyone understand what effect that behavior had on the image of the College. Just as we got each group up to be recognizable adults, we made the mistake of graduating them and bringing in a new freshman class."

Brewster concedes ambivalent feelings towards having to enforce student discipline, and quotes the late John O'Con- nor: "It's important to remember everyone will look like a choirboy in the morning and turn out to be one of your friend's children. But rules are rules, and if undergraduates are not given definite signals when they break them, then we as educators have failed." Either Brewster at Dartmouth was less easy-going than believed, or his present experience as the president of a women's college has changed his perspective.

Finally. Dean Manuel acknowledges his image as an authoritarian, calling it a "truth as a perception, but not so much as a conclusion." Declining to comment on the difference in disciplinary philosophy between himself and Brewster, the dean instead emphasizes the need to define clearly a code of conduct and what happens when it is transgressed. But the fact that everyone operates on "good information" doesn't make administering punishment any easier for Manuel: "You agonize, sure, but you sometimes have a situation literally so outrageous in the minds of the majority of the committee that a person's education has to be interrupted. Then again, I've had people come back and thank me for being suspended, saying it's the best thing that ever happened to them."

Of more concern to Manuel right now is the committee's image with the College community. Because of the confidentiality in which most of the proceedings occur, a cloud of secrecy seems to enshroud the CCSC, often engendering misconceptions. When an ill-informed student levels a blast of criticism at the committee, the temptation to counter with privileged evidence has to be resisted. "Most people don't understand this confidentiality," says Manuel. "But take, for example, a student up for an honor-code violation. It's almost a ScarletLetter situation." Even if the student is found innocent, he explains, the publicity of an open hearing can seriously damage his or her reputation. To alleviate these communication problems, the committee is planning a series of newsletters and annual reports to let all the students know who they are and what they do.

Considering both the level of his position and the length of his tenure, it is understandable that the dean has the largest single influence on discipline at the College. But student or faculty representatives on the committee can and do stand in opposition to certain prevailing currents from above. Upon joining the CCSC this fall, Professor of Mathematics Edward Brown knew that his personal philosophy would conflict not only with other committee members, but also with the traditional stance of private colleges. Brown disagrees specifically with the belief in the College as the student's parent away from home. Instead of correcting an undergraduate's moral philosophy through the concept of in loco parentis, he feels the committee - like the local authorities - should act only when a student's behavior violates the rights of others or destroys property. But even then Dartmouth should not be in the "punishment game."

Unlike the courts, the committee can attempt to understand both the human motivations behind a "crime," and the effect discipline will have later on a student's personal growth. As the committee's insight deepens through con- sidering these two factors of "context" and "future," a given case moves from a type to an individual. Precedent from even just a few years back is often no longer valid, based as it is upon shifting rules and personalities.

The committee's final decision, Brown thinks, should not be a punitive action, but one that will correct the situation in the best way possible for both the student and the school, even if it is painful in the shortrun. Thus, he usually sees disciplinary suspension not as a "punishment" but as "time to sit down and think."

The problem Seymour sees with the increased time and energy this type of concern demands is not an issue for Brown. For him the costs are worthwhile. "Efficiency," Brown says, "is just not an important criterion for human relations. This is not an efficient way to administer discipline, but it's a good way. And the benefit of having authority rest in various groups is quite high. Besides, the costs aren't that big - we spend most of our time on academic issues rather than conduct."

Brown, in effect, summarizes and affirms both of the major trends in discipline since Eleazar's days of kicking in the doors. One is a movement away from encumbering the student with legislated morals - no disorderly night-walking and the like - and toward providing him or her with the freedom and responsibility of any individual over 18 in the outside world. The second trend is the "democratization" of the discipline procedure: the move from the rule-of-the-dean to the rule-of-the- committee, and to a growing respect for a diversity of viewpoints and the "due-process" rights of a student.

No doubt some perceive these changes as the regrettable encroachment by an external society on the internal matters of the College. No doubt some even condemn them for what is considered Dartmouth's present renaissance of behavioral aberrations. And yet a look at the past indicates that while the current species of undergraduate behaves - or in this case misbehaves - little differently from his ancestor, the amount of responsibility he is expected to assume is considerably greater. Such is the progress of liberal arts since Dr. Bartlett's menagerie: fewer keepers and inmates, more educators and students.

From presidential dictatorship to due process

Gentlemen, I came here in trie capacity ofPresident of Dartmouth College, to takecharge of young gentlemen, but if, by anyunforeseen circumstance, it becomesnecessary for me to assume the management of a menagerie of young monkeysand baboons, I trust I shall be equal to thatundertaking also.

The following entries were taken from the dailylog of the Campus Police. Duty for the eightmember regular force can be mundane (one officer admits that unlocking rooms for studentswho forget their keys is pretty boring),sometimes comic, occasionally tense. In thetradition of Joe Friday, all of the names here and some of the details — have been changed toprotect the innocent, who are few indeed.

8:00 a.m. Lt. Barden and Officer Birchassumed duty. Previous entries reviewed.Cruiser inspected for cleanliness and requiredequipment. Tour of duty commenced. 10:35a.m. Transported student from Streeter Hall toDick's House (crutches). 11:05 a.m. Deliveredletter to student from Dean's Office.

1:55 p.m. Pet in room 302B Cohen Hall, seereport. 4:20 p.m. Evicted skaters from Occompond, unsafe. 6:40 p.m. Noise complaint at S.Mass., stereo turned down, no report. 10:40p.m. Unplugged coffee pot in office of theMusic Department. 12:08 a.m. Snow fight atNew Hampshire, unfounded at this time. 12:15a.m. Snow fight at Hitchcock, broken windows,see report. 12:20 a.m. Checked Occom Pond,reported a small hole to Hanover P. D., possible

2:55 p.m. Pig found in Campus Police office.Returned to Psi U. 3:15 p.m. Stolen bicyclelocated in New Hampshire Hall. Owner will benotified. 11:05 p.m. Report of fire at 19 SchoolStreet. 11:45 p.m. Report of a car with fourtown subjects in it trying to pick a fight withsome black students. On arrival the town subjects had moved on and the students didn't wantto press it further.

8:15 a.m. Colby-Sawyer Student left behind, seereport. 9:05 a.m. Watchman #7 reported a dogin the Commons Room between Cohen andBissell, there was no one around and no nameon the dog, the dog was put outside.

9:40 a.m. Report of flood on second floor ofCummings Hall. Unit #9O notified. 2:50 p.m.Natalie Jenson '79 in office to get weapon. 5:15p.m. Student called to say someone had brokenhis window in room 301B Little, checked outcomplaint and talked with a Gigi Risberg '81who said she had done it with her hockey stick.8:05 a.m. Report of chickens in President's office.

Tim Taylor '79 is one of this year's undergraduate editors. He also is a special officer on the Campus Police.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

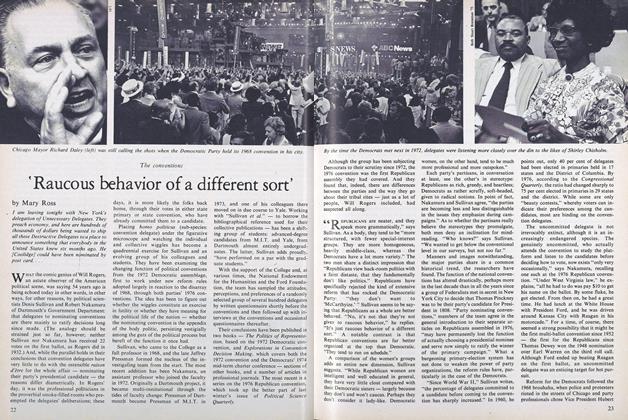

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureParadise Lost or Paradise Regained?

December 1978 -

Feature

FeatureGOOD NEWS

December 1978 -

Article

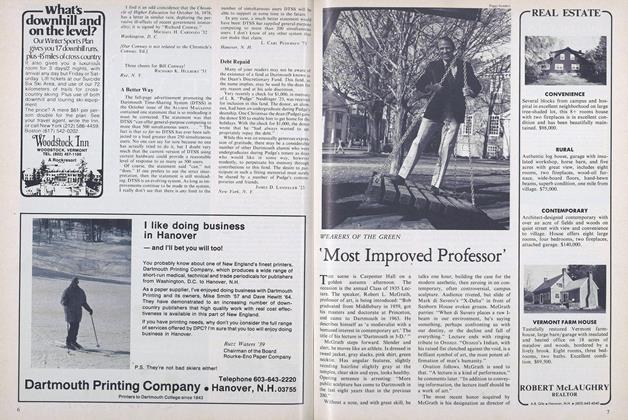

Article'Most Improved Professor'

December 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleStraight Shooter

December 1978 By D.M.N. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

December 1978 By DAVID R. BOLDT

Tim Taylor

Features

-

Cover Story

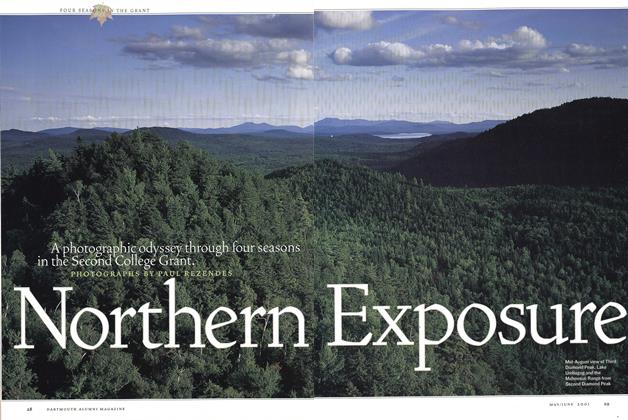

Cover StoryNorthern Exposure

May/June 2001 -

Cover Story

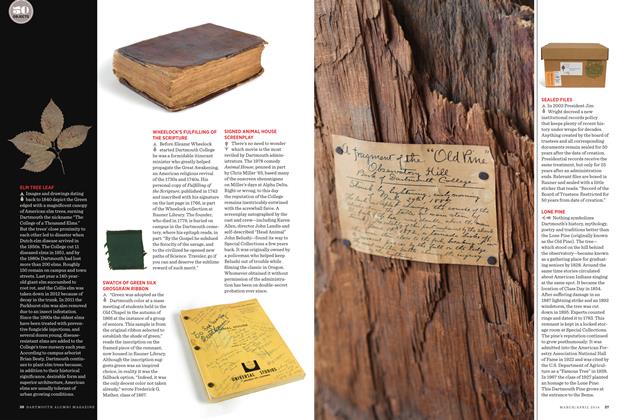

Cover StoryWHEELOCK’S FULFILLING OF THE SCRIPTURE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

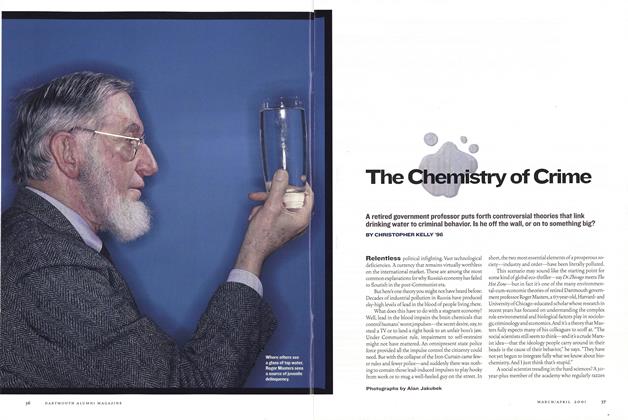

FeatureThe Chemistry of Crime

Mar/Apr 2001 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

Feature

FeatureChallenge

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Colleen Sullivan Bartlett '79 -

Feature

FeatureOh, You Shouldn't Have!

MAY 1992 By JONATHAN DOUGLAS -

FEATURE

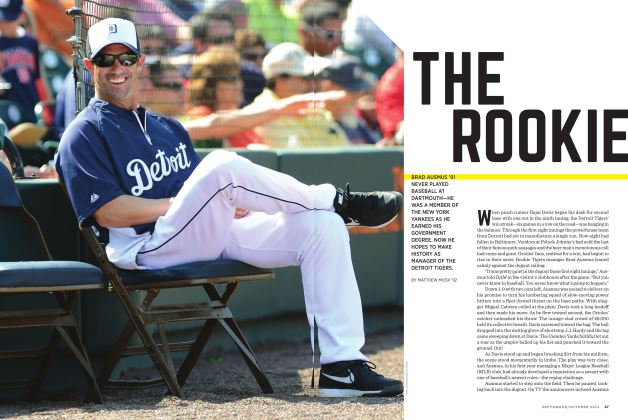

FEATUREThe Rookie

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92