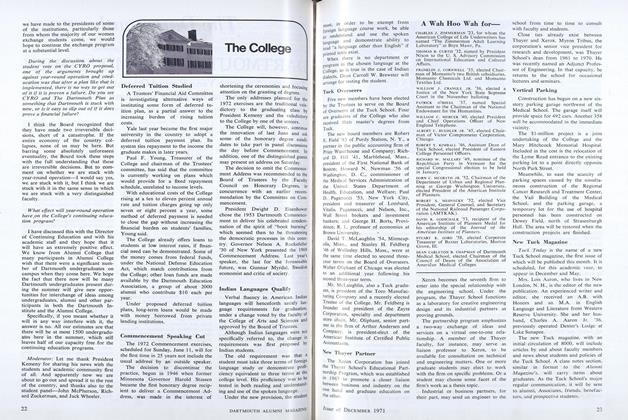

THE scene is Carpenter Hall on a golden autumn afternoon. The occasion is the annual Class of 1935 Lecture. The speaker, Robert L. McGrath, professor of art, is being introduced: "Bob graduated from Middlebury in 1959, got his masters and doctorate at Princeton, and came to Dartmouth in 1963. He describes himself as 'a medievalist with a bemused interest in contemporary art.' The title of his lecture is 'Dartmouth in 3-D."

McGrath steps forward. Slender and alert, he moves like an athlete. Is dressed in tweed jacket, gray slacks, pink shirt, green necktie. Has angular features, slightly receding hairline slightly gray at the temples, clear skin and eyes, looks healthy. Opening sentence is arresting: "More public sculpture has come to Dartmouth in the last eight years than in the previous 200."

Without a note, and with great skill, he talks one hour, building the case for the modern aesthetic, then zeroing in on contemporary, often controversial, campus sculpture. Audience riveted, but slide of Mark di Suvero's "X-Delta" in front of Sanborn House evokes groans. McGrath parries: "When di Suvero places a raw Ibeam in our environment, he's saying something, perhaps confronting us with our destiny, or the decline and fall of everything." Lecture ends with ringing tribute to Orozco. "Orozco's Indian, with his raised fist clenched against the void, is a brilliant symbol of art, the most potent affirmation of man's humanity."

Ovation follows. McGrath is used to that. "A lecture is a kind of performance," he comments later. "In addition to conveying information, the lecture itself should be a work of art."

The most recent honor acquired by McGrath is his designation as director of the Alumni College for the next three years, replacing his close friend Jim Epperson. Having participated in five Alumni College programs, the new director has clear ideas about the future. "The extraordinarily successful academic formula that has evolved over 15 years is essentially sound. I won't tamper with that, but I will place more emphasis on the historical past. This year we are going to study 'The French Revolution and the Napoleonic Era: Art, History, and Science, 1760-1830.' "

"I think continuing education is one of the most valuable things we do at Dartmouth," McGrath says. "I wish we were able to do more of it. It is basic to the philosophy of the institution that education extends well beyond the granting of degrees. We don't want to deal with our alumni simply in terms of football and fund-raising the way some colleges do.

"Unfortunately, the size of our Alumni College is limited by logistics. Last year we had 320 participants and turned away about 80. If demand continues to skyrocket, we might have to hire a dean of admissions. Imagine having to explain to your child that you were turned down by Alumni College!

"Teaching alumni is very different from teaching undergraduates. The alumni have broader perspectives, and they come well prepared with opinions that are shaped by the wide diversity of their backgrounds. I thoroughly enjoy their enthusiasm and their wonderful gratitude.

"The goal of Alumni College? I'd say it is to reaffirm the fact that the life of the mind can be exciting."

A born perfectionist with a penchant for self-discipline, McGrath is an expert skier, tennis player, distance runner, mountain climber, mnemonist, as well as a serious scholar. He has a charming, intelligent wife, four remarkably successful children, and enjoys the life of a country squire in a rambling white house in Norwich. Since the world does not automatically love a winner, his detractors say he is covered with luck. He replies: "I think you make your own good fortune, you don't just fall into it. I've always had a vision of the life I lead."

Things weren't always as rosy as they are now. Half-Irish, half-French, he was an only child in a devout Roman Catholic home. He says he grew up lonely. "Perhaps that's why I have four kids. I envy people who have faith. My belief system is described by Erwin Panofsky's statement, 'The humanist respects tradition but rejects authority.' "

As his father was in the foreign service, McGrath spent his childhood in Libya and Iran. Upon graduating from Catholic High School in Portland, Oregon, he took off for the University of Grenoble because he wanted to ski. He did well in international competition, and the American team coach persuaded him to go to Middlebury.

"I'd never heard of Dartmouth," McGrath recalls. "College wasn't a happy time for me, either. I had a lot of growing up to do. I was big on ski racing at Middlebury. Then, to my surprise, I got so interested in books and ideas and social life - I abandoned racing altogether."

Asked how he came to Dartmouth, McGrath replies, "When I got my doctorate in 1963, I had lots of job offers-those were the halcyon days of education -but the only place I wanted to go was Dartmouth. I love the outdoors, especially northern New England. Even though Yankees don't adopt auslanders, I'm up for adoption. There's something medieval about Vermont's agrarian social organization. It's like living at the end of the Middle Ages, with the interstate representing the intrusion of a threatening and alien culture." (This is McGrath's ultimate compliment. He is suspicious of everything that has occurred since 1300.)

McGrath's specialization choice was influenced by Kurt Weitzmann, Princeton's great medieval scholar. The multidimensional aspects of the Middle Ages and the fabled anonymity of its artists particularly appeal to him. No cult of personality there. His favorite painter is Jan Van Eyck who, he says, is "everybody-who-has-ever-seen- him's favorite, but unfortunately you have to go to Bruges to know him." Three other painters he responds to are Poussin, Velazquez, and Rembrandt. ("Who can fail to be moved by Rembrandt?")

Everything is grist for McGrath's mill when he lectures on art. He shows Norman Rockwell's triple-self-portrait, a SaturdayEvening Post cover, to illustrate the complexity of visual perception. He discusses di Suvero's "frivolous swing" on "X-Delta" (where McGrath disports in the photograph) in terms of Fragonard's frilly lady flying high on a rococco swing, an imaginative juxtaposition in anybody's book. He finds Christo's 26-mile "Running Fence" a "confidence-building aesthetic gesture" and Beverly Pepper's earthworks sculpture "Thel" (in front of the Fairchild Center) "seemingly austere but reaching into the environment in a very romantic way." In modern art his personal barometer is Frank Stella ("Andover and Princeton, perfect credentials") who explains his enigmatic paintings by saying, "What you see is what you see."

An art historian, by definition, is required to verbalize things essentially nonverbal. For McGrath this is a constant struggle - which would surprise his listeners. He has the ability to distill an entire era in one sentence: "In the 19th century, American art was stretched by a constant polarity between the genteel world of John Singer Sargent and the gritty industrial world painted by John Sloan and the Ashcan School."

Robert McGrath says he is proud of Dartmouth's collection, particularly the ancient Assyrian reliefs and the Greek amphora in Carpenter Hall. He thinks the College's greatest modern treasure is Picasso's "Guitar on a Table," a recent gift from Nelson Rockefeller. Agreeing with Robert Frost that "artists are the antennae of the race," he wishes that Dartmouth's Art History Department were larger. "We have only five on our faculty and we average about eight majors a year, but what we lack in quantity I believe we make up in quality. Harvard takes only ten students into its graduate program. In 1976, three of the ten, thirty per cent of the entire class, came from Dartmouth." He also takes pride in the fact that Dartmouth will soon have a foreign study program in art history in Florence.

On the professor's desk is a small metal sculpture made of welded copper. It is called "Society" and has a single brass horizontal piece representing the "nonconformist." His son Rob made the piece, and the brass plate on the pedestal may tell us something about the art historian's family life. The engraved inscription reads: "Art schmart/It's a living?"

Like their father, the McGrath children excel in athletics. Rob, a Dartmouth freshman, is on the U.S. National Development Ski Team. Felix is one of the top New England high school skiers and Susie and Bill both ski for Hanover High School.

When he's accused of being too competitive, Bob McGrath retorts, "Sure I'm competitive, intensely so. I like to win but I don't apologize for that. My battle is essentially with myself. Books like Zen in theArt of Archery and The Inner Game ofTennis helped me realize that selfawareness is the goal, not ascendancy over others."

This man's self-awareness is impressive. McGrath on McGrath: "My greatest strength is a keen memory. I have a high energy quotient, am precise, punctual, and neat. I think there is a correlation between an orderly desk and an orderly mind. My greatest weakness is a certain glibness, even smugness. I'm also driven, impatient, stubborn, insomniac, and fastidious to a fault. My contribution to scholarship hasn't been powerfully original so far [brightens up] but I may be a late bloomer."

Epperson on McGrath: "Robert is a puzzling fellow. Though we've been friends 14 years, he's always surprising. He can be charming, affable, tactful one day and the next day be the opposite. He's impressively learned - moves freely in French, German, and Italian - and appears to have total recall of art history. He goes to the heart of things with rapidity and explains them with lucidity. A contentious Irishman, not a political Irishman, he'd rather solve problems than soothe injured feelings."

McGrath demands as much of his students as he does of himself. Known as a tough teacher, he is formal, even aloof, with them, but there is evidence that he is held in some affection. At an art majors party, he was presented with a scroll citing him as "Most Improved Professor" who, in four years, had progressed "From Nasty to Grumpy."

As one chats with McGrath, varied facets of his complex personality flash by: Skepticism: "The closest I can come to a hero is Thomas Jefferson. To have heroes, you need a certain ignorance of biographical detail."

Ambition: "I'm a hopeless and unregenerate achiever. I like to set goals and cross them off. The quest is invariably more enjoyable than the attainment."

Discrimination: "I used to enjoy fine foods and wine but I've given that up, a hopeless cause in America. Perhaps I developed over-refined tastes living in France."

Irony: "The cocktail party is probably America's greatest contribution to 20thcentury civilization."

Talent: "I never thought I'd be as creative or as imaginative as I am. I knew I had certain gifts of intellect, but sometimes 1 surprise myself."

Honesty: "No, I wouldn't say I'm egotistical, but others would."

Asked to evaluate his teaching, McGrath shrugs. "It's hard to define yourself apart from your institution. I'm happy with my 15 years as a teacher here and I continue to grow in this vital and enjoyable role.

"For me Dartmouth is simultaneously frustrating and rewarding. I'm frustrated by my inability to have a greater impact on the place. I'd like to bring the gospel of art to every student at this college where, unfortunately, the humanities are not seen as the core of human experience, but rather as frosting. On the other hand, I find it highly rewarding to encounter, almost without exception, extraordinarily bright, creative students and to work with such splendid colleagues. The possibilities at Dartmouth are enormous. After all, even granite can be sculpted."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

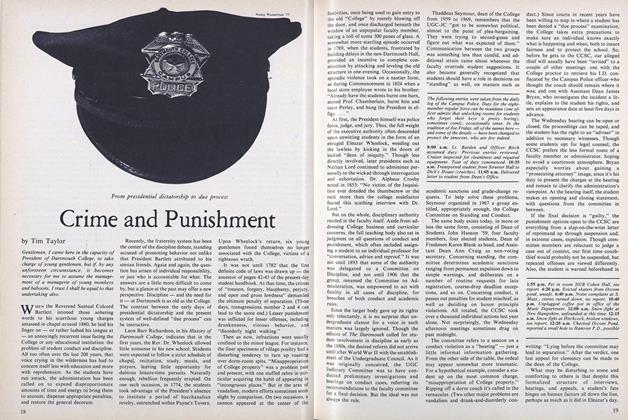

FeatureCrime and Punishment

December 1978 By Tim Taylor -

Feature

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureParadise Lost or Paradise Regained?

December 1978 -

Feature

FeatureGOOD NEWS

December 1978 -

Article

ArticleStraight Shooter

December 1978 By D.M.N. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

December 1978 By DAVID R. BOLDT

NARDI REEDER CAMPION

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

OCTOBER 1982 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

MAY • 1988 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA Full Disabled Life

October 1995 -

Article

Article"Man Better Man"

SEPTEMBER 1982 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

Feature"Those Who Miss The Joy, Miss All"

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

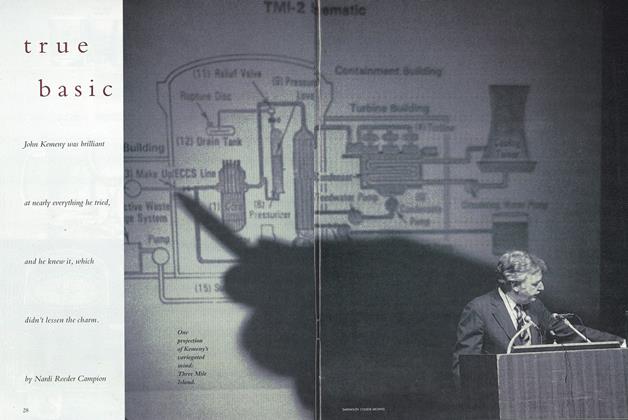

Cover Story

Cover StoryTrue Basic

May 1993 By Nardi Reeder Campion