WHEN David Baldwin first taught a course on Vietnam, it was not in a college classroom but at Ft. Gordon, Georgia. His students were American and Vietnamese field grade officers - majors and colonels - attending the U.S. Army Civil Affairs School. His "message" was that the "hearts and minds" of the Vietnamese people would never be won through force. The year was 1962.

Seventeen years later, Baldwin is teaching another course on Vietnam, this time as a professor of government at the College.

Comfortably ensconced within his office on the second floor of Silsby Hall, Baldwin is dwarfed on one side by a huge wall-size bookcase and surrounded on all others by the usual professorial clutter: rows of ominously titled volumes on international economics and foreign policy, stacks of article off-prints from unfamiliar journals, even a list of popular music related to his current subject and a diplomatic board game called "Origins." Over his desk hangs an engraving of a blacksmith beating a sword into a ploughshare. With his dark curly hair and moustache and casual manner of dress, Baldwin looks and sounds younger than his actual 42 years. On a warm spring day last month, between occasional student visits, he thought back to those early years of the war.

Fresh from graduate school at Princeton, the young lieutenant was assigned, because of his political science background, to Civil Affairs, a division set up after the Second World War to oversee military/civilian relations in occupied zones. With few areas left to administer by the late fifties, Civil Affairs turned its attention toward the growing problem in Southeast Asia. Unfortunately, the overall lack of knowledge about Vietnam was frightening. As Baldwin recently told a newspaper reporter, he and his fellow officers "knew nothing of Asia ... no wonder we lost. It was the blind leading the blind."

Nevertheless, Baldwin and the other instructors continued to stress the importance of maintaining a good relationship with the civilian population: "In retrospect, what we were saying was more important than it was thought by most at the time. We were telling them that the problem of dealing with insurgency warfare is 10 per cent military and 90 per cent social and economic. But professional military men were suspicious of Civil Affairs officers. They felt we just got in the way of the real work to be done."

Baldwin remembers that any concept of a restraining international law especially met with cynicism. "There were a lot of winks," he recalls. "Winks from the kind of guy who sat through class but came out saying, 'All this talk of law is fine, but you and I know it's not that way in a real war.' People received the message, but it just wasn't getting through."

Baldwin's course today on Vietnam in part discusses what went wrong with those students who failed to learn the lesson of that first class. Through his own lectures, guest speakers, films, novels, and book- length treatments of the war, Baldwin hopes his College Course 7 will, in the formidable terms of the syllabus, cover "the historical, legal, moral, psychological, political, economic, military, and cultural dimensions of the Vietnam War ... in order to determine the war's impact on American society, the international system, and the prospects for world order."

These last words, "world order," provide a key phrase for Baldwin and his teaching career. Arriving at Dartmouth in 1965, he found the major academic forum for discussing current events - the Great Issues course - standing, as he puts it, on its "last leg." With too much material for too little time, the course often touched only superficially on certain issues of global importance. Nevertheless, its demise left an even worse vacuum.

In 1975, Baldwin was appointed John Sloan Dickey Third Century Professor in the Social Sciences, a position that allowed him to do something about the void. Every Third Century chair - one in each of the three undergraduate divisions and in each graduate school - is accompanied by a substantial gift in time and money: A professor's obligations to his department are cut in half, and he receives $10,000 a year for five years to spend on some form of innovative teaching. Baldwin decided to establish a series of "college" - that is, non-departmental - courses to explore topics related to "world order," in both economic and political terms. The first two courses grew directly out of Baldwin's own research interests, one on limits to growth, the other on multi-national corporations.

Though just as concerned with world order, the Vietnam course stemmed not from Baldwin's own interests - he claims neither Asian nor military expertise - but from a need he perceived at Dartmouth. Despite growing up with the war each night on television, current college students were generally too young at the time to comprehend its political and moral context. Baldwin noticed a growing apathy among most students toward the war, and a growing naivete and ignorance among those few who did care.

"By 1976 or '77," explains Baldwin, "I realized that many students had some bizarre ideas. For instance, in one case study we did for an international politics course, I asked the students to locate Vietnam on a map. About half couldn't even do that, and that was after we'd read a book on the war. Or another example, some thought that North and South Vietnam were two separate countries, and had been for a long time. They were unaware of the artificiality of that division."

During his 14 years at Dartmouth, Baldwin has witnessed not only this recent cooling of concern, but also each of the various shifts in student opinion as antiwar protests emerged, swelled, peaked, and dissipated. "Initially, many students were all for the war, as long as someone else fought it. They felt college students were different - that they should be exempt. When anti-war protests did begin to grow, each gradual escalation was about three years behind those at places like Berkeley or Columbia." As Baldwin remembers, 1966-67 saw small demonstrations on the Green and silent vigils before the Hopkins Center. By 1968-69, most of the students and faculty were against the war in some sense, though perhaps not actively demonstrating. The anti-ROTC take-over of Parkhurst Hall occurred in the spring of 1969, and what Baldwin considers the peak of the protests followed a year later, with classes shut down over the American incursion into Cambodia.

Baldwin's own sentiments more or less paralleled changes on the campus, passing through several stages. In the early years, he defended the involvement, maintaining that our actions were often misunderstood. But as the war escalated, he became increasingly disillusioned: "I think My Lai was the final turning point. What happened there went directly counter to everything we had taught in Civil Affairs. I once considered that some civilian casualties were inevitable in guerrilla warfare, but it's hard to argue that a one-year-old baby is going to shoot you. Acts like that are only associated with the Nazis."

Though Baldwin holds his own convictions on the war, he is not so much interested in communicating them to his students as he is in getting the students themselves to think about the war, to initiate a process of analysis and evaluation. To aid in the process, Baldwin has lined up an impressive, and diverse, series of outside sources to provide a complex approach. Guest speakers include Jonathan Mirsky, a Southeast Asian expert and an outspoken critic of the war during his nine years at Dartmouth; Gloria Emerson, New York Times reporter and author of Winners andLosers; Telford Taylor, professor at Columbia Law School and chief counsel for the prosecution at the Nuremberg war crimes trials; General William Westmore land, commander of the U.S. Military forces in Vietnam from 1964-1968; and former Secretary of State Dean Rusk.

Baldwin's reading list covers a similarly wide spectrum of opinion, from General Westmoreland's A Soldier Reports as a defense of the war, through "middle-of- the-road" books like Frances FitzGerald's Fire in the Lake, to entirely critical works like Daniel Ellsberg's Papers on the War. He also planned several film screenings including the 1975 documentary Hearts andMinds, and two widely differing dramas, John Wayne's The Green Berets and the recent academy award winner, The DeerHunter.

What Baldwin's students will make out of this conflicting and still controversial mass of information and opinion is unclear. Baldwin himself resists judging the course's success or failure on the conclusions drawn, repeating instead his emphasis on the process of thinking critically. "I'm not sure what the lessons are that ought to be learned. But there are lessons drawn of which I'm very suspicious. For example, we used more force against Vietnam than against any other nation in history. And yet instead of concluding that there are just some things that can't be done with force, many draw a lesson like, 'If you're going to use force, use a lot of it fast.' "

Other erroneous conclusions Baldwin cites are the notion that the United States was hurt by too much TV and press coverage - "We lost the war in the editorial pages of the New York Times" - or that now the United States should pull back with an isolationist response to world affairs. Baldwin notes this last issue is of particular importance to a speaker like Dean Rusk, who wants to dwell not so much on the mistakes of the past but on what they mean for tomorrow.

And ultimately, this interest in the future is also Baldwin's major concern in "CoCo 7." As he puts it,. "American foreign policy can never be the same as in the fifties and early sixties. We have to understand the changes in America's image of itself, its conception of the role it should play in the world, and the image other nations have of it. We have to come to grips with Vietnam in terms of its significance for the future, and not just to re-open the wounds of the past."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

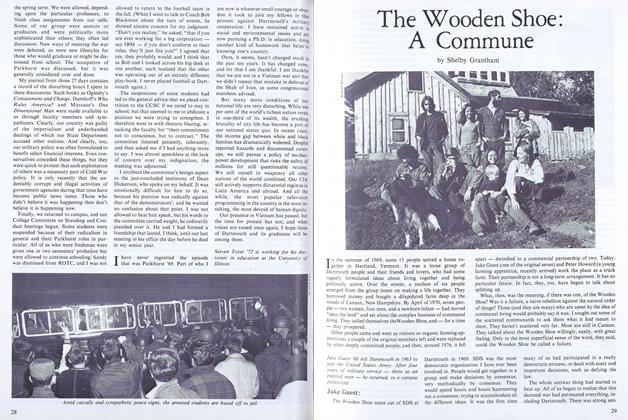

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWhen They Resisted

May 1979 By Steven E. Tozer -

Feature

FeatureA Three-story House on Bramhall Avenue

May 1979 By Douglas Andrews -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

May 1979 By WILLIAM A. CARTER -

Article

ArticleJudicial Clerk

May 1979 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1927

May 1979 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK

TIM TAYLOR

Article

-

Article

ArticleSecretaries Having 100% Record for the Year Magazine Class Notes, 1933-1934

June 1934 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

MAY | JUNE 2016 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1942 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleLATE SCORES

February 1962 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH EDUCATIONAL ASSOCIATION

January, 1925 By Rbert J. Holmes '09, Treasurer -

Article

ArticleSHORT PAGES FROM ONE LONG LIFE

December, 1925 By Roy Brackett