She's great. She jumps all around, snaps at you — her French is flawless. And she's so tiny, you think you can swat her like a fly. But don't try it! — one of Sova Pheng's French 1 students

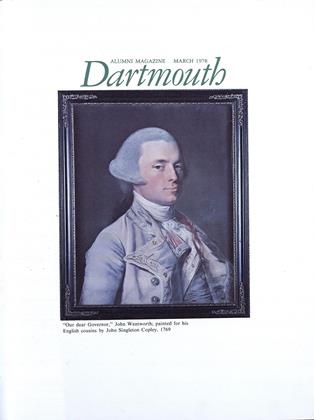

INDEED, don't be fooled by her four-foot eleven-inch size, or her tiny voice, or the sweet smile on her face. For Sovathana Pheng '79 is no fly, butter- or otherwise. The vivacious, 19-year-old daughter of an expatriate Cambodian diplomat has enough steel in her to withstand schooling in four different countries, one month in a refugee camp after the fall of Phnom Penh — even three years at Dartmouth.

As one of six Indochinese refugees brought to the College in the fall of 1975 through the efforts of director of public programs Frederick L. Hier '44 and Tucker Foundation dean Warner R. Traynham '57, Sova's pre-Dartmouth story reads nothing like the average college freshman's, "with regular high school and clubs and stuff — I never much went in for that, and besides, who had time?" She was born in Phnom Penh of Cambodian parents, the eldest of a family of six children. Her father's position as attache in the Cambodian diplomatic corps took the family soon after Sova's birth to Paris, where her first recollections begin. "I don't remember anything of Cambodia before the war," she says. "My parents tell me things and show me pictures, and I say, 'Oh yeah? That's what it was like?' "

Because of her early childhood in France, Sova began and continued her schooling in the French system, even after the family's return to Cambodia in 1962. Sova's original introduction to the French language, coupled with the presence of French schools in almost any country to which her father might be assigned, made a French education the most practical. "Besides," says Sova with a wry twist and an "ahem" tilt to her eyebrows, "in Cambodia, it's the thing to do. To have a French education is a very prestigious thing." Hence, the flawless French which even one of her French professors at Dartmouth admits is "as good as any I've ever heard from a student."

After leaving Paris, the Phengs spent four years back in Phnom Penh before Sova's father was reassigned — this time to England. It was there that she first learned English from neighbor children, as she continued in the French system at a lycee in London. Since the younger children were starting school at that time, English was the language they spoke among themselves then — and still do — though they remain fluent in both French and Cambodian and speak Cambodian with their parents. "Sometimes we mix the languages up, or 'play' with them — use French, say, if we don't want someone in the room to know what we're saying — but that's not very often," she comments.

During the family's stay in London, the political situation at home was such that the Cambodian government "wanted to find out which side "everyone was falling on," Sova explains. Consequently, her father was asked if he supported the original government in Phnom Penh or the Communist provisional government in the People's Republic of China. "All our relatives were in Phnom Penh," she says, "and my father didn't want us to be in exile — he wanted us to be able to go home again. So he supported Phnom Penh." Which in terms of Sova's future at the College, turned out to be a wise choice: "If he had opted for China, we'd still be there, and we'd be there forever."

The Phengs' return to Cambodia after four years in England is a vaguely unpleasant memory for Sova. "It wasn't that bad then," she says, "but we were in Phnom Penh, and I do remember rockets falling once in a while. Cambodia was so different than my parents remembered it and told us about."

Their return was short-lived, however, sor a year later Pheng — by then a second secretary in the diplomatic corps, three steps below ambassador — was reassigned to Taiwan. There, because of the educational possibilities of the American university system, Sova ceased her French education and enrolled in Taiwan American School, from which she received her diploma in three years. Why so fast?

"My mother wanted me to finish up quickly," she says with a chuckle, "because with the situation back home we didn't know what was going to happen, and it was better to get my diploma and be done with it." Again, a wise decision: "If I hadn't graduated, I would never have been able to come to Dartmouth, because I wouldn't have been a high school graduate."

Compared with the French schools, the American school in Taiwan was fair: "In a French school, there aren't many activities — you go to school and that's about it. In T.A.S., there were some clubs and things, but they were pretty much of a joke. It didn't matter, though — I liked everything in school."

When Phnom Penh fell in the spring of 1975, all possibility of the Phengs returning to Cambodia was cut off, and they fled, along with 140,000 other Indochinese, to the United States. "At first," Sova says, "we thought about going to France, because we had more friends there." It was the presence of a cousin's family in San Francisco, coupled with better educational possibilities, that led them to come to the States. Like all Indochinese refugees, they first came through a staging center in Guam, whence they were assigned to one of four refugee camps on the mainland. The Phengs drew Indiantown Gap, Penn- sylvania.

Sova is vehement in her dislike for the camp. "All I wanted to do was get out of there," she says. "First of all, it was crowded. I don't even know how many of us they had there. Then, we all felt depersonalized: everyone was treated as a whole. That was especially bad because we were not just from one country. There were Vietnamese, Cambodians — and we don't get along at all. So people were antagonistic toward each other. Then the G.I.s were very condescending to us — they didn't want to know us as people; we were just Indochinese, and that's it. It wasn't fun at all — it was very tense."

Her experience in the camp left a mark on Sova. "I used to be very idealistic — I still am, to some extent — and I'd heard a lot about racism and discrimination, but I'd never been subjected to it. Then I heard some of the comments people were making about us, and I thought — so that's what discrimination is. It shattered some of my illusions.

"Even in high schools, where I was the only Indochinese, I'd never been treated that way. I guess when you're the only one, people treat you differently. I had fit right in."

It was during the family's stay at Indiantown Gap that Sova was first contacted by the College. At Hier's and Traynham's instigation and with the blessing of President Kemeny, the deans, and the offices of admissions, financial aid, and housing, Dartmouth had undertaken to bring six refugees — three students and three workers — to the College on a provisional basis. Although Sova's original plans were to attend Stanford or Berkeley while living with her family in San Francisco, Dartmouth attracted her right off because it was small, personal, and very "collegey." After interviews on campus, Sova was admitted as a freshman on a provisional basis. With a B average for her first year, she became a fully matriculated undergraduate in her sophomore year at the College.

The Phengs, meanwhile, moved to San Francisco under the sponsorship of their cousin. Sova's father is now an accountant in a hospital and teaches English to Indochinese students, and her mother works part-time as a day-care mother. Her brothers and sisters want to follow her to a good college — "but not necessarily Dartmouth, because I've been here. They want to spread it around."

After a brief stint as a pre-med biology major — "my parents always thought it would be a nice thing for me to do, and I didn't have any idea what I wanted to do, so ..." — Sova has settled on a French major and has tentative plans to teach. She has served as an apprentice teacher in French and has exploited a natural flair for drama by directing and acting in French plays, with Candide and Tartuffe to her credit. This summer she hopes to be a group leader for Language Study Abroad in France "and just have fun."

Though previously a "city kid," Sova has found no problems in adjusting to the campus. "I really like the nature. I've always lived in the city, and it's nice to be out in the country, although —" she tosses her head and smiles — "you do miss city life occasionally." The greatest "cultural clash," as she puts it, comes when she spends leave terms at home with her family. "My parents are very traditional, very protective. There are certain things that nice Cambodian girls just don't do, like have dates. Since we've been in the States they've had to loosen up a bit, but I still get cross-examined occasionally. I try to explain to them that I'm not traditional, but parents do have a grip on you." As for the Cambodian custom of arranging marriages, Sova "would have a lot to say if that happened to me!"

In the end, though, the parental tie never gets too binding. "I mean, my mother says, 'If we didn't trust you, we wouldn't have let you go to Dartmouth.' " Which says about as much for the College — and for Sova Pheng — as anything.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

March 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

March 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

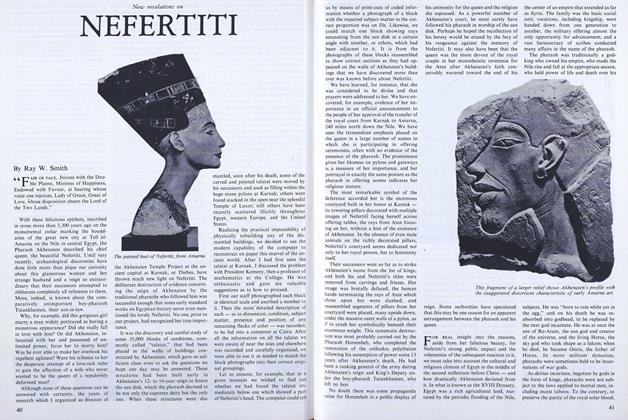

FeatureNEFERTITI

March 1978 By Ray W. Smith -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

March 1978 -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

March 1978 By R.H.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1978 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR.