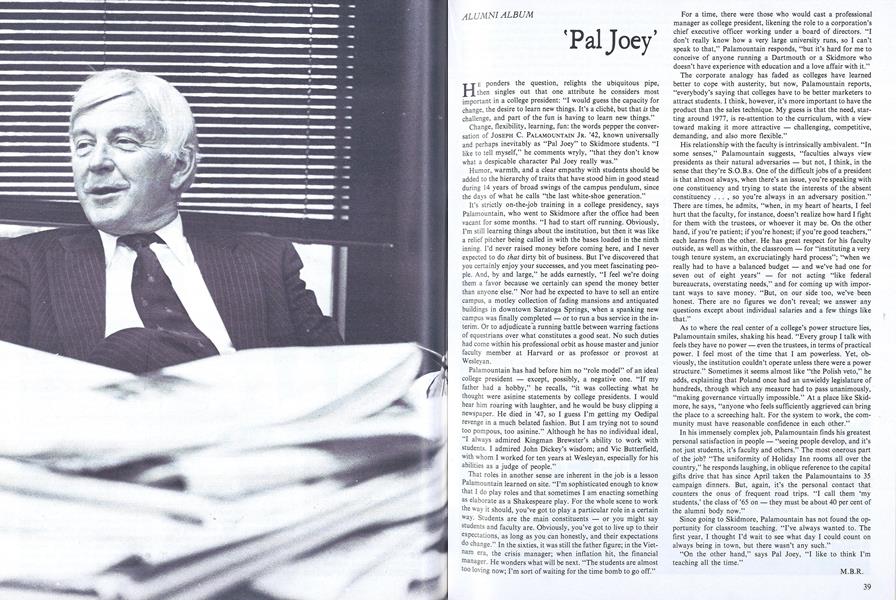

HE ponders the question, relights the übiquitous pipe, then singles out that one attribute he considers most important in a college president: "I would guess the capacity for change, the desire to learn new things. It's a cliche, but that is the challenge, and part of the fun is having to learn new things."

Change, flexibility, learning, fun: the words pepper the conversation of JOSEPH C. PALAMOUNTAIN JR. '42, known universally and perhaps inevitably as "Pal Joey" to Skidmore students. "I like to tell myself," he comments wryly, "that they don't know what a despicable character Pal Joey really was."

Humor, warmth, and a clear empathy with students should be added to the hierarchy of traits that have stood him in good stead during 14 years of broad swings of the campus pendulum, since the days of what he calls "the last white-shoe generation."

It's strictly on-the-job training in a college presidency, says Palamountain, who went to Skidmore after the office had been vacant for some months. "I had to start off running. Obviously, I'm still learning things about the institution, but then it was like a relief pitcher being called in with the bases loaded in the ninth inning. I'd never raised money before coming here, and I never expected to do that dirty bit of business. But I've discovered that you certainly enjoy your successes, and you meet fascinating people. And, by and large," he adds earnestly, "I feel we're doing them a favor because we certainly can spend the money better than anyone else." Nor had he expected to have to sell an entire campus, a motley collection of fading mansions and antiquated buildings in downtown Saratoga Springs, when a spanking new campus was finally completed — or to run a bus service in the interim. Or to adjudicate a running battle between warring factions of equestrians over what constitutes a good seat. No such duties had come within his professional orbit as house master and junior faculty member at Harvard or as professor or provost at Wesley an.

Palamountain has had before him no "role model" of an ideal college president — except, possibly, a negative one. "If my father had a hobby," he recalls, "it was collecting what he thought were asinine statements by college presidents. I would hear him roaring with laughter, and he would be busy clipping a newspaper. He died in '47, so I guess I'm getting my Oedipal revenge in a much belated fashion. But I am trying not to sound too pompous, too asinine." Although he has no individual ideal, "I always admired Kingman Brewster's ability to work with students. I admired John Dickey's wisdom; and Vic Butterfield, with whom I worked for ten years at Wesleyan, especially for his abilities as a judge of people."

That roles in another sense are inherent in the job is a lesson Palamountain learned on site. "I'm sophisticated enough to know that I do play roles and that sometimes I am enacting something as elaborate as a Shakespeare play. For the whole scene to work the way it should, you've got to play a particular role in a certain way. Students are the main constituents — or you might say students and faculty are. Obviously, you've got to live up to their expectations, as long as you can honestly, and their expectations do change." In the sixties, it was still the father figure; in the Vietnam era, the crisis manager; when inflation hit, the financial manager. He wonders what will be next. "The students are almost too loving now; I'm sort of waiting for the time bomb to go off."

For a time, there were those who would cast a professional manager as college president, likening the role to a corporation's chief executive officer working under a board of directors. "I don't really know how a very large university runs, so I can't speak to that," Palamountain responds, "but it's hard for me to conceive of anyone running a Dartmouth or a Skidmore who doesn't have experience with education and a love affair with it."

The corporate analogy has faded as colleges have learned better to cope with austerity, but now, Palamountain reports, "everybody's saying that colleges have to be better marketers to attract students. I think, however, it's more important to have the product than the sales technique. My guess is that the need, starting around 1977, is re-attention to the curriculum, with a view toward making it more attractive — challenging, competitive, demanding, and also more flexible."

His relationship with the faculty is intrinsically ambivalent. "In some senses," Palamountain suggests, "faculties always view presidents as their natural adversaries — but not, I think, in the sense that they're S.O.B.s. One of the difficult jobs of a president is that almost always, when there's an issue, you're speaking with one constituency and trying to state the interests of the absent constituency . . . , so you're always in an adversary position." There are times, he admits, "when, in my heart of hearts, I feel hurt that the faculty, for instance, doesn't realize how hard I fight for them with the trustees, or whoever it may be. On the other hand, if you're patient; if you're honest; if you're good teachers," each learns from the other. He has great respect for his faculty outside, as well as within, the classroom — for "instituting a very tough tenure system, an excruciatingly hard process"; "when we really had to have a balanced budget — and we've had one for seven out of eight years" — for not acting "like federal bureaucrats, overstating needs," and for coming up with important ways to save money. "But, on our side too, we've been honest. There are no figures we don't reveal; we answer any questions except about individual salaries and a few things like that."

As to where the real center of a college's power structure lies, Palamountain smiles, shaking his head. "Every group I talk with feels they have no power - even the trustees, in terms of practical power. I feel most of the time that I am powerless. Yet, obviously, the institution couldn't operate unless there were a power structure." Sometimes it seems almost like "the Polish veto," he adds, explaining that Poland once had an unwieldy legislature of hundreds, through which any measure had to pass unanimously, "making governance virtually impossible." At a place like Skidmore, he says, "anyone who feels sufficiently aggrieved can bring the place to a screeching halt. For the system to work, the community must have reasonable confidence in each other."

In his immensely complex job, Palamountain finds his greatest personal satisfaction in people — "seeing people develop, and it's not just students, it's faculty and others." The most onerous part of the job? "The uniformity of Holiday Inn rooms all over the country," he responds laughing, in oblique reference to the capital gifts drive that has since April taken the Palamountains to 35 campaign dinners. But, again, it's the personal contact that counters the onus of frequent road trips. "I call them 'my students,' the class of '65 on — they must be about 40 per cent of the alumni body now."

Since going to Skidmore, Palamountain has not found the opportunity for classroom teaching. "I've always wanted to. The first year, I thought I'd wait to see what day I could count on always being in town, but there wasn't any such."

"On the other hand," says Pal Joey, "I like to think I'm teaching all the time."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

FeatureE – i – e – i – o

June 1979 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

FeatureExit with a Flourish

June 1979 By Beverly Foster -

Feature

FeatureEncouraging growth, affirming the educational process

June 1979 By Robert Kilmarx -

Article

ArticleCommencement

June 1979 By James L. Farley -

Article

Article'Radical' with a Cause

June 1979 By Tim Taylor