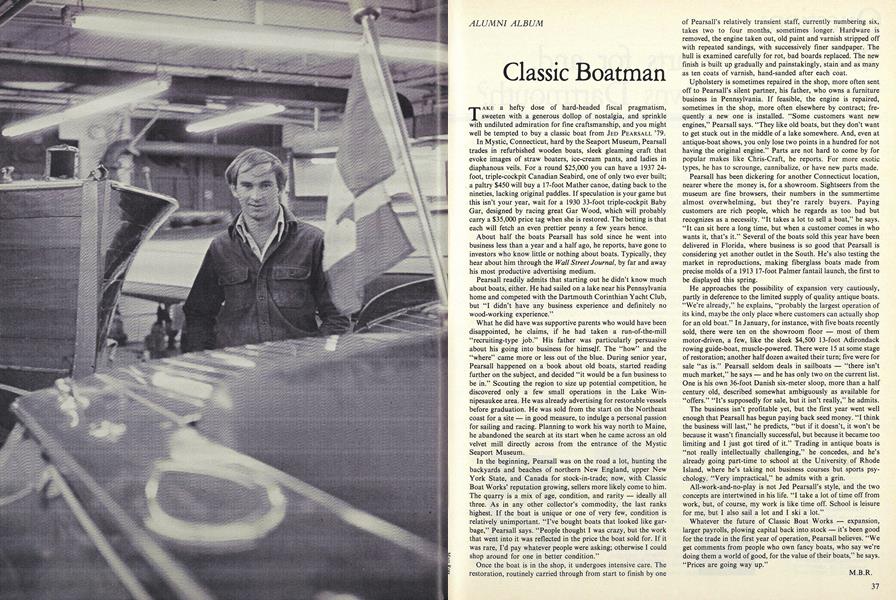

TAKE a hefty dose of hard-headed fiscal pragmatism, sweeten with a generous dollop of nostalgia, and sprinkle with undiluted admiration for fine craftsmanship, and you might well be tempted to buy a classic boat from JED PEARSALL '79.

In Mystic, Connecticut, hard by the Seaport Museum, Pearsall trades in refurbished wooden boats, sleek gleaming craft that evoke images of straw boaters, ice-cream pants, and ladies in diaphanous veils. For a round $25,000 you can have a 1937 24- foot, triple-cockpit Canadian Seabird, one of only two ever built; a paltry $450 will buy a 17-foot Mather canoe, dating back to the nineties, lacking original paddles. If speculation is your game but this isn't your year, wait for a 1930 33-foot triple-cockpit Baby Gar, designed by racing great Gar Wood, which will probably carry a $35,000 price tag when she is restored. The betting is that each will fetch an even prettier penny a few years hence.

About half the boats Pearsall has sold since he went into business less than a year and a half ago, he reports, have gone to investors who know little or nothing about boats. Typically, they hear about him through the Wall Street Journal, by far and away his most productive advertising medium.

Pearsall readily admits that starting out he didn't know much about boats, either. He had sailed on a lake near his Pennsylvania home and competed with the Dartmouth Corinthian Yacht Club, but"I didn't have any business experience and definitely no wood-working experience."

What he did have was supportive parents who would have been disappointed, he claims, if he had taken a run-of-the-mill "recruiting-type job." His father was particularly persuasive about his going into business for himself. The "how" and the "where" came more or less out of the blue. During senior year, Pearsall happened on a book about old boats, started reading further on the subject, and decided "it would be a fun business to be in." Scouting the region to size up potential competition, he discovered only a few small operations in the Lake Winnipesaukee area. He was already advertising for restorable vessels before graduation. He was sold from the start on the Northeast coast for a site in good measure, to indulge a personal passion for sailing and racing. Planning to work his way north to Maine, he abandoned the search at its start when he came across an old velvet mill directly across from the entrance of the Mystic Seaport Museum.

In the beginning, Pearsall was on the road a lot, hunting the backyards and beaches of northern New England, upper New York State, and Canada for stock-in-trade; now, with Classic Boat Works' reputation growing, sellers more likely come to him. The quarry is a mix of age, condition, and rarity ideally all three. As in any other collector's commodity, the last ranks highest. If the boat is unique or one of very few, condition is relatively unimportant. "I've bought boats that looked like garbage," Pearsall says. "People thought I was crazy, but the work that went into it was reflected in the price the boat sold for. If it was rare, I'd pay whatever people were asking; otherwise I could shop around for one in better condition."

Once the boat is in the shop, it undergoes intensive care. The restoration, routinely carried through from start to finish by one of Pearsall's relatively transient staff, currently numbering six, takes two to four months, sometimes longer. Hardware is removed, the engine taken out, old paint and varnish stripped off with repeated sandings, with successively finer sandpaper. The hull is examined carefully for rot, bad boards replaced. The new finish is built up gradually and painstakingly, stain and as many as ten coats of varnish, hand-sanded after each coat.

Upholstery is sometimes repaired in the shop, more often sent off to Pearsall's silent partner, his father, who owns a furniture business in Pennsylvania. If feasible, the engine is repaired, sometimes in the shop, more often elsewhere by contract; frequently a new one is installed. "Some customers want new engines," Pearsall says. "They like old boats, but they don't want to get stuck out in the middle of a lake somewhere. And, even at antique-boat shows, you only lose two points in a hundred for not having the original engine." Parts are not hard to come by for popular makes like Chris-Craft, he reports. For more exotic types, he has to scrounge, cannibalize, or have new parts made.

Pearsall has been dickering for another Connecticut location, nearer where the money is, for a showroom. Sightseers from the museum are fine browsers, their numbers in the summertime almost overwhelming, but they're rarely buyers. Paying customers are rich people, which he regards as too bad but recognizes as a necessity. "It takes a lot to sell a boat," he says. "It can sit here a long time, but when a customer comes in who wants it, that's it." Several of the boats sold this year have been delivered in Florida, where business is so good that Pearsall is considering yet another outlet in the South. He's also testing the market in reproductions, making fiberglass boats made from precise molds of a 1913 17-foot Palmer fantail launch, the first to be displayed this spring.

He approaches the possibility of expansion very cautiously, partly in deference to the limited supply of quality antique boats. "We're already," he explains, "probably the largest operation of its kind, maybe the only place where customers can actually shop for an old boat." In January, for instance, with five boats recently sold, there were ten on the showroom floor most of them motor-driven, a few, like the sleek $4,500 13-foot Adirondack rowing guide-boat, muscle-powered. There were 15 at some stage of restoration; another half dozen awaited their turn; five were for sale "as is." Pearsall seldom deals in sailboats "there isn't much market," he says and he has only two on the current list. One is his own 36-foot Danish six-meter sloop, more than a half century old, described somewhat ambiguously as available for "offers." "It's supposedly for sale, but it isn't really," he admits.

The business isn't profitable yet, but the first year went well enough that Pearsall has begun paying back seed money. "I think the business will last," he predicts, "but if it doesn't, it won't be because it wasn't financially successful, but because it became too limiting and I just got tired of it." Trading in antique boats is "not really intellectually challenging," he concedes, and he's already going part-time to school at the University of Rhode Island, where he's taking not business courses but sports psychology. "Very impractical," he admits with a grin.

All-work-and-no-play is not Jed Pearsall's style, and the two concepts are intertwined in his life. "I take a lot of time off from work, but, of course, my work is like time off. School is leisure for me, but I also sail a lot and I ski a lot."

Whatever the future of Classic Boat Works ― expansion, larger payrolls, plowing capital back into stock ― it's been good for the trade in the first year of operation, Pearsall believes. "We get comments from people who own fancy boats, who say we're doing them a world of good, for the value of their boats," he says. "Prices are going way up."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTenure: an academic necessity

April 1981 By A. E. DeMaggio -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith -

Feature

FeatureTenure: the tragedy of the slaughterhouse

April 1981 By Peter W. Travis -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTops in Their Class

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBeethoventorte

April 1981

M.B.R

Article

-

Article

ArticleSecretaries Meeting

APRIL 1929 -

Article

ArticleNew College Movies

January 1935 -

Article

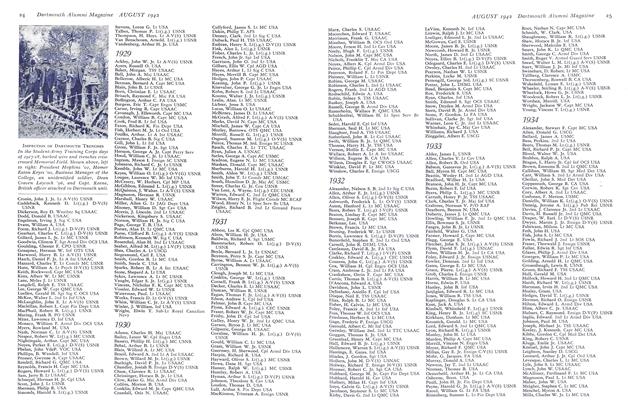

ArticleKey to Abbreviations of Branches of Service

August 1942 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Article

ArticleNotebook

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By ELI BURAKIAN '00 -

Article

ArticleEastern Massachusetts

December 1976 By GARRET G. RASMUSSEN '71