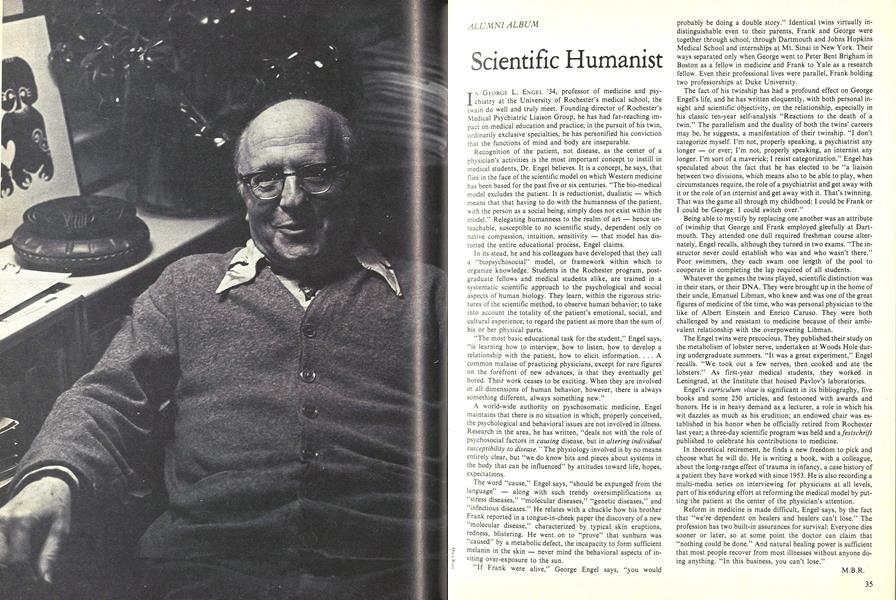

I N GEORGE L. ENGEL '34, professor of medicine and psyX chiatry at the University of Rochester's medical school, the twain do well and truly meet. Founding director of Rochester's Medical Psychiatric Liaison Group, he has had far-reaching impact on medical education and practice; in the pursuit of his twin, ordinarily exclusive specialties, he has personified his conviction that the functions of mind and body are inseparable.

Recognition of the patient, not disease, as the center of a physician's activities is the most important concept to instill in medical students, Dr. Engel believes. It is a concept, he says, that flies in the face of the scientific model on which Western medicine has been based for the past five or six centuries. "The bio-medical model excludes the patient. It is reductionist, dualistic which means that that having to do with the humanness of the patient, with the person as a social being, simply does not exist within the model." Relegating humanness to the realm of art hence unteachable, susceptible to no scientific study, dependent only on native compassion, intuition, sensitivity that model has distorted the entire educational process, Engel claims.

In its stead, he and his colleagues have developed that they call a "biopsychosocial" model, or framework within which to organize knowledge. Students in the Rochester program, postgraduate fellows and medical students alike, are trained in a systematic scientific approach to the psychological and social aspects of human biology. They learn, within the rigorous strictures of the scientific method, to observe human behavior; to take into account the totality of the patient's emotional, social, and cultural experience; to regard the patient as more than the sum of his or her physical parts.

"The most basic educational task for the student," Engel says, "is learning how to interview, how to listen, how to develop a relationship with the patient, how to elicit information.... A common malaise of practicing physicians, except for rare figures on the forefront of new advances, is that they eventually get bored. Their work ceases to be exciting. When they are involved in all dimensions of human behavior, however, there is always something different, always something new."

A world-wide authority on Pyschosomatic medicine, Engel maintains that there is no situation in which, properly conceived, the psychological and behavioral issues are not involved in illness. Research in the area, he has written, "deals not with the role of psychosocial factors in causing disease, but in altering individualsusceptibility to disease." The physiology involved is by no means entirely clear, but "we do know bits and pieces about systems in the body that can be influenced" by attitudes toward life, hopes, expectations.

The word "cause," Engel says, "should be expunged from the language" along with such trendy oversimplifications as stress diseases," "molecular diseases," "genetic diseases," and infectious diseases." He relates with a chuckle how his brother Frank reported in a tongue-in-cheek paper the discovery of a new molecular disease," characterized by typical skin eruptions, redness, blistering. He went on to "prove" that sunburn was caused by a metabolic defect, the incapacity to form sufficient melanin in the skin never mind the behavioral aspects of inviting over-exposure to the sun.

If Frank were alive," George Engel says, "you would probably be doing a double story." Identical twins virtually indistinguishable even to their parents, Frank and George were together through school, through Dartmouth and Johns Hopkins Medical School and internships at Mt. Sinai in New York. Their ways separated only when George went to Peter Bent Brigham in Boston as a fellow in medicine and Frank to Yale as a research fellow. Even their professional lives were parallel, Frank holding two professorships at Duke University.

The fact of his twinship has had a profound effect on George Engel's life, and he has written eloquently, with both personal insight and scientific objectivity, on the relationship, especially in his classic ten-year self-analysis "Reactions to the death of a twin." The parallelism and the duality of both the twins' careers may be, he suggests, a manifestation of their twinship. "I don't categorize myself. I'm not, properly speaking, a psychiatrist any longer or ever; I'm not, properly speaking, an internist any longer. I'm sort of a maverick; I resist categorization." Engel has speculated about the fact that he has elected to be "a liaison between two divisions, which means also to be able to play, when circumstances require, the role of a psychiatrist and get away with it or the role of an internist and get away with it. That's twinning. That was the game all through my childhood: I could be Frank or I could be George. I could switch over."

Being able to mystify by replacing one another was an attribute of twinship that George and Frank employed gleefully at Dartmouth. They attended one dull required freshman course alternately, Engel recalls, although they turned in two exams. "The instructor never could establish who was and who wasn't there." Poor swimmers, they each swam one length of the pool to cooperate in completing the lap required of all students.

Whatever the games the twins played, scientific distinction was in their stars, or their DNA. They were brought up in the home of their uncle, Emanuel Libman, who knew and was one of the great figures of medicine of the time, who was personal physician to the like of Albert Einstein and Enrico Caruso. They were both challenged by and resistant to medicine because of their ambivalent relationship with the overpowering Libman.

The Engel twins were precocious. They published their study on the metabolism of lobster nerve, undertaken at Woods Hole during undergraduate summers. "It was a great experiment," Engel recalls. "We took out a few nerves, then cooked and ate the lobsters." As first-year medical students, they worked in Leningrad, at the Institute that housed Pavlov's laboratories.

Engel's curriculum vitae is significant in its bibliography, five books and some 250 articles, and festooned with awards and honors. He is in heavy demand as a lecturer, a role in which his wit dazzles as much as his erudition; an endowed chair was established in his honor when he officially retired from Rochester last year; a three-day scientific program was held and a festschrift published to celebrate his contributions to medicine.

In theoretical retirement, he finds a new freedom to pick and choose what he will do. He is writing a book, with a colleague, about the long-range effect of trauma in infancy, a case history of a patient they have worked with since 1953. He is also recording a multi-media series on interviewing for physicians at all levels, part of his enduring effort at reforming the medical model by putting the patient at the center of the physician's attention.

Reform in medicine is made difficult, Engel says, by the fact that "we're dependent on healers and healers can't lose." The profession has two built-in assurances for survival: Everyone dies sooner or later, so at some point the doctor can claim that "nothing could be done." And natural healing power is sufficient that most people recover from most illnesses without anyone doing anything. "In this business, you can't lose."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIn Another Country

May 1980 By Beth Ann Baron -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

May 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticlePainting Medicos Have Both "Life" and "Work"

May 1980 By D.C.G -

Article

ArticleVox

May 1980 By Norman R. Carpenter '53