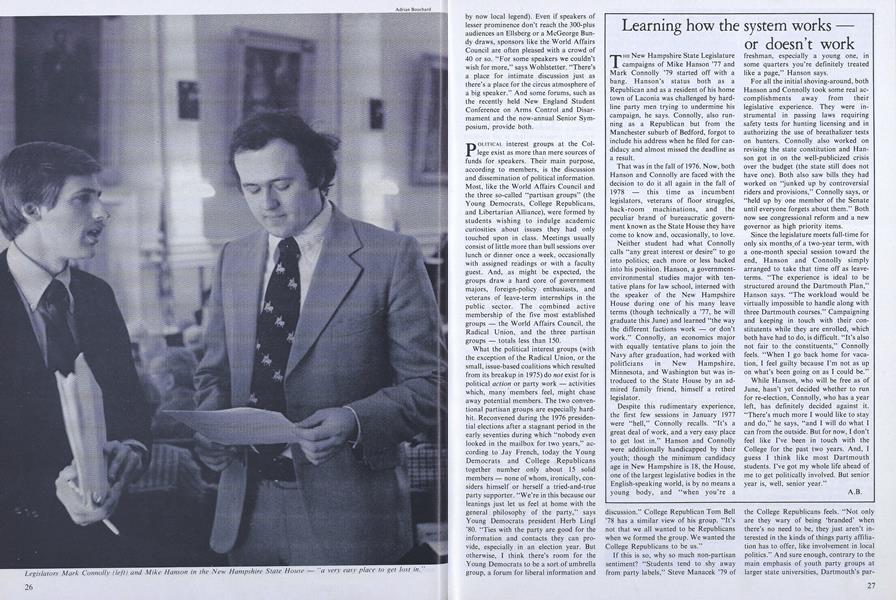

THE New Hampshire State Legislature campaigns of Mike Hanson '77 and Mark Connolly '79 started off with a bang. Hanson's status both as a Republican and as a resident of his home town of Laconia was challenged by hardline party men trying to undermine his campaign, he says. Connolly, also running as a Republican but from the Manchester suburb of Bedford, forgot to include his address when he filed for candidacy and almost missed the deadline as a result.

That was in the fall of 1976. Now, both Hanson and Connolly are faced with the decision to do it all again in the fall of 1978 - this time as incumbent legislators, veterans of floor struggles, back-room machinations, and the peculiar brand of bureaucratic government known as the State House they have come to know and, occasionally, to love.

Neither student had what Connolly calls "any great interest or desire" to go into politics; each more or less backed into his position. Hanson, a government-environmental studies major with tentative plans for law school, interned with the speaker of the New Hampshire House during one of his many leave terms (though technically a '77, he will graduate this June) and learned "the way the different factions work - or don't work." Connolly, an economics major with equally tentative plans to join the Navy after graduation, had worked with politicians in New Hampshire, Minnesota, and Washington but was introduced to the State House by an admired family friend, himself a retired legislator.

Despite this rudimentary experience, the first few sessions in January 1977 were "hell," Connolly recalls. "It's a great deal of work, and a very easy place to get lost in." Hanson and Connolly were additionally handicapped by their youth; though the minimum candidacy age in New Hampshire is 18, the House, one of the largest legislative bodies in the English-speaking world, is by no means a young body, and "when you're a freshman, especially a young one, in some quarters you're definitely treated like a page," Hanson says.

For all the initial shoving-around, both Hanson and Connolly took some real accomplishments away from their legislative experience. They were instrumental in passing laws requiring safety tests for hunting licensing and in authorizing the use of breathalizer tests on hunters. Connolly also worked on revising the state constitution and Hanson got in on the well-publicized crisis over the budget (the state still does not have one). Both also saw bills they had worked on "junked up by controversial riders and provisions," Connolly says, or "held up by one member of the Senate until everyone forgets about them." Both now see congressional reform and a new governor as high priority items.

Since the legislature meets full-time for only six months of a two-year term, with a one-month special session toward the end, Hanson and Connolly simply arranged to take that time off as leaveterms. "The experience is ideal to be structured around the Dartmouth Plan," Hanson says. "The workload would be virtually impossible to handle along with three Dartmouth courses." Campaigning and keeping in touch with their constitutents while they are enrolled, which both have had to do, is difficult. "It's also not fair to the constituents," Connolly feels. "When I go back home for vacation, I feel guilty because I'm not as up on what's been going on as I could be."

While Hanson, who will be free as of June, hasn't yet decided whether to run for re-election, Connolly, who has a year left, has definitely decided against it. "There's much more I would like to stay and do," he says, "and I will do what I can from the outside. But for now, I don't feel like I've been in touch with the College for the past two years. And, I guess I think like most Dartmouth students. I've got my whole life ahead of me to get politically involved. But senior year is, well, senior year."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCould it be that the political animals are hibernating?

May 1978 By Anne Bagamery -

Feature

FeatureRev. Frisbie's Wonderful Discovery

May 1978 By James L. Farley -

Feature

FeatureCastles in the Clouds

May 1978 By George Hathorn -

Feature

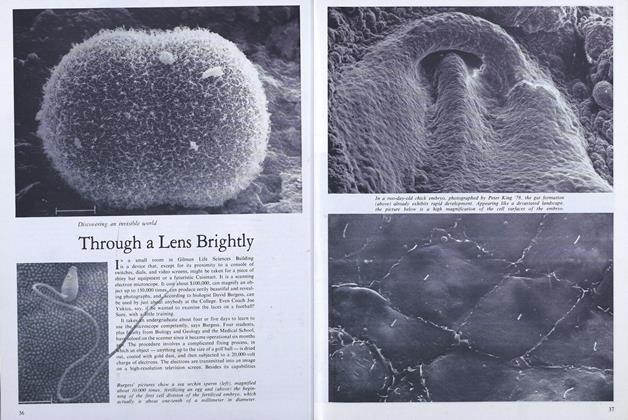

FeatureThrough a Lens Brightly

May 1978 -

Article

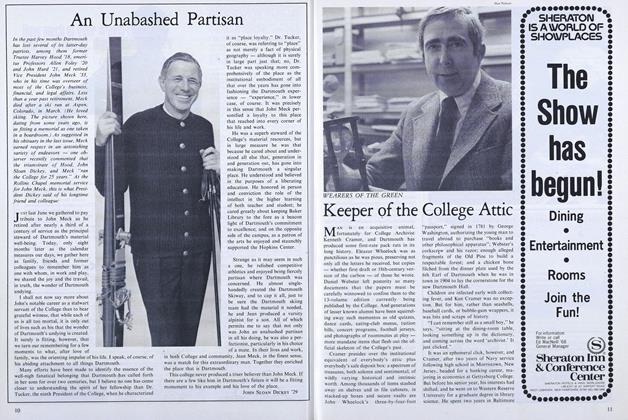

ArticleKeeper of the College Attic

May 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMy Dog Likes It Here

May 1978 By COREY FORD