The episode known as Parkhurst '69

IN 1968, like many high-school students who had received letters of acceptance from Dartmouth, I was basking in the sunshine of my senior year. I had been captain of the football and wrestling teams, had been selected to spend the previous summer in Europe as an American Field Service student, and had received such awards as "Scholar Athlete" and "Representative Student" at my high school in Springfield, Illinois. I reveled in my good fortune and future. I was 18. Exactly a year later, I was in Rockingham County Jail, serving a 30-day sentence for my participation in the occupation of Dartmouth's Parkhurst Hall.

To the folks at home, the events of May 1969 were clear evidence that I had changed dramatically from the boy they knew. Undoubtedly, the SDS had warped another young, impressionable mind.

But for me and for many others of that time, political conviction did not arrive suddenly; it had been growing quietly for years. Mario Savio and the Berkeley free- speech movement had come into our Midwest home in Life magazine; Martin Luther King had marched, and blacks had been beaten on home television; and Bob Dylan sang "Masters of War" and "The Times, They Are a Changin' " ion the radio. And they all spoke of ideals that home and school taught me to respect: freedom, justice, and equality among people.

The war in Vietnam loomed large for many working-class high-school friends who were not college-bound. My friend Brad and I talked about the war while working as lifeguards in the evenings at the YMCA. We declared, almost as if making a pact, that we would not kill anyone for reasons that were not our own.

When I registered at Dartmouth, I needed money to help pay expenses, and I was offered a National Defense Loan. I read the oath I would have to sign: it committed me to defending the country's interests in war. Although I was not a pacifist, I realized that I could in effect be swearing to fight in Vietnam; and I refused to sign, taking a College loan instead. I was slowly committing myself to defend my attitudes, but I did not know how far I wanted to go.

Clearly, my politics were not complete prior to the ROTC campaign - nor are they now - but the issue was serious enough that I felt compelled to respond to it. I listened to both sides with a sincere desire, I think, to learn the truth of the situation. I had no axe to grind either with the Dartmouth administration, which treated me with respect, or with my parents, to whom I felt, as now, a deep love and attachment. (That relationship in particular constituted the strongest argument against militant action. I knew it would be hard for them to accept.)

DISCUSSIONS of the war and of U.S. military policy continued from my first weeks at Dartmouth. Most of my friends seemed more sophisticated than I in the political issues at hand. Henry articulated his interpretation of the violence of the 1968 Chicago convention. Fred and I discussed U.S. foreign policy and the role of our military in supporting dictatorships in Southeast Asia and Latin America. And Sandy, my roommate, agonized with me over the relationship of Dartmouth's ROTC program to U.S. military organization. He had reason to agonize; he was at Dartmouth on an ROTC scholarship. It became clear to both of us that he was not merely on a scholarship program; he was engaged in military training.

I recall arguing a conservative position in many of these discussions, but my arguments were weak. The Chicago police brutalities, like the CIA-supported assassinations in Vietnam, were understandable, but they were inexcusable.

Current events and much current political literature supported the radical view. Together with Michael, we were five freshmen from the same dormitory, and although none of us had "radical" backgrounds, we reinforced one another in our views. On the other side were the arguments of our dormmates. The common line of debate they most often presented was that we had no right to interfere with the right of others to choose military training at Dartmouth. Our common response was this: If our military force were shelling villages and killing thousands of Vietnamese men, women, and children, then good cause had to be shown; if none were forthcoming, then we could respect no one's right to join and aid such an organization. In fact, it was our obligation to interfere.

The effort to divest Dartmouth of its ROTC involvement developed out of a growing national perception that we were engaged in an irrational, immoral war and that there were no significant legal actions that one could take to stop it. The campaign developed slowly and tentatively; and although I was only a freshman, I found that my suggestions were considered as seriously as were those of professors and older students. Everyone had opportunity to be heard.

We were all new to this sort of thing, and our campaign proceeded like any other: We distributed home-made leaflets, made posters, set up information booths, canvassed, carried signs, and initiated a Take- a-Professor-to-Lunch program of dialogues with faculty members. We argued that if a major institution such as Dartmouth refused to participate in the U.S. military program, it would add significantly to the growing swell of sentiment against the war.

The faculty, however, adopted a compromise proposal which did, in fact, phase out ROTC over the next few years. That the resolution included plans to consider re-institution of ROTC in four years after we had graduated from Dartmouth appeared to reflect not a moral stand, but an effort to appease the student body. Not only was the option to maintain ROTC included in the resolution, but all military programs would continue to operate for the benefit of those students already engaged in military training. The College would reduce its commitment to the military effort, then, but only temporarily.

A meeting of anti-ROTC students had been scheduled in College Hall for May 6, and I attended. I was on my way to give a guitar lesson to a Hanover boy, so I had my guitar. I had no plans to do anything political after the meeting, as we had lost the faculty vote and I was very discouraged. I did not see how one more meeting could have any effect.

I remember seeing Jonathan, a dormmate, outside College Hall. He asked me if I planned to participate if a demonstration followed the meeting. I said no, that I had something to do afterward. He said, "We all have other things to do."

I was late, and the meeting inside was short. It was the biggest crowd I ever saw at anti-ROTC meetings, numbering perhaps 250 people. Dave Green was on the stage saying that the time for talking was over; it was time for action. He said he was going over to the administration building; anyone else was welcome. There was no haranguing, no rationalizing. He strode down from the stage and out the door.

Only a sophomore, Dave Green had uncanny timing; it was good strategy and effective leadership. He felt, I think, that one more democratic meeting of suggestions and resolutions was a futile prospect. He was angry, he wanted support, and he got it. Most of the crowd streamed over to Parkhurst Hall. We had staged one sit-in meeting there before, and it was not clear what this new action would be.

I followed with ambivalence. I had engaged in a series of discussions with Dean of Freshmen Albert I. Dickerson '30, and we had reviewed at length the arguments of the anti-ROTC campaign. He represented to me the best possible source for the conservative view. The subject of a Parkhurst take-over had come up because it was, in view of the events at Harvard, Columbia, and other campuses, a "natural" option for students who saw themselves as part of a larger movement. It was also the symbolic and functional center of the College; the offices of the President and the deans were there.

During my conversations with Dickerson, I had said I doubted that such la takeover would occur, but that if it did, I expected to participate. Dean Dickerson said he hoped I would not, and I genuinely respected his concern. He always seemed fair to me and took a sincere interest in my progress. I knew he would be disappointed in my militant activity, but I felt a greater responsibility to the issue. The more of us who participated, I reasoned, the less easily this gesture of indignation could be dismissed by the faculty, alumni, and general public.

I did, however, tell the dean that I expected to be a moderating influence if the occupation became violent. Campus violence between students and police had become familiar through the headlines, and I felt it served no purpose. It was not naive to suppose, as facts later confirmed, that non-violence would have to be defended in the midst of a militant action. It was naive to think that if students behaved nonviolently, then police would necessarily follow suit.

At least a hundred of us - perhaps many more - entered the building at first, and to my knowledge the plan of action was not fully communicated to many people. I first became aware of what some demonstrators had in mind when I saw building employees leaving the building in a hurry. I went straight to Dean Dickerson's office. I don't know if I had already seen Dean Thad Seymour pushed and pulled down the stairs and out the door by the surging students, or if I saw that only later, but I tried to persuade Dickerson to leave under his own power. He would have none of it, and he was eventually carried out in his office chair. Because of his age, I feared for his safety on the stairway and helped him keep his balance until he was outside. He treated the entire episode as a kind of prank, smiling and admonishing throughout.

By the time I got back into the building, nearly all of the employees were out, with the exception of a faculty member in a basement office who was said to have heart trouble. Word spread that he was to be left alone; there seemed to be an unspoken agreement that our action should cause no injury. To my knowledge, it caused none.

At this time people began milling throughout the building, taking stock of the situation and talking over strategy. It was certainly not clear what we could accomplish by occupying the building.

For the first time I saw some of my friends from French Hall. First Henry, then Michael, Fred, and finally, to my surprise, my roommate Sandy. We had not resolved to participate in a building occupation, and I doubt they had any more idea than I did whom we would find inside. Each of us had decided on his own to enter the building, and we greeted each other with a shared sense of delight and apprehension. It was great to see friends, but what had we got ourselves into?

I telephoned the boy whose guitar lesson I was supposed to give, telling him I would have to miss this afternoon.

THROUGH the years, almost countless memories from the hours inside the building have drifted vividly back. There are some I don't want to forget.

While it was still light, for example, I wandered through the President's office, where students were occupied watching the crowd gathering outside. Climbing a narrow stairway and a ladder to the roof, I found my roommate and Bill Geller, a wild-haired, pink-shirted, indomitable sophomore busily hanging a crimson banner on the flagstaff. Many in the crowd were incensed by this, and yelled obscenities-and threats up at us. I clearly remember several who chanted "Hang the commies!"

I could see signs protesting the action and some supporting it. Students were running from all directions, and the crowd was already more than the yard could hold. The street was blocked with the curious, the sympathetic, and the vociferously hostile. I recall my extreme puzzlement that these students could become so upset over the temporary occupation of property and yet remain calm in the face of hundreds of thousands of dead and mutilated bodies less than a day's jet-ride away. I was shaken by what seemed an impossibly wide gulf between that group and those in the building.

Returning to the group on the main stairway, I found them discussing the next steps to be taken. Early in the occupation, there had been no need to identify oneself as "there to stay" or "only there for a while." It wasn't clear that anyone was going to stay for very long. Various ideas were now considered, and some decided to stay until forcibly ejected. It would, even if the ROTC issue was lost, demonstrate that this issue was not just student whim; it was a principle that we were willing to risk our college careers to defend.

It was at that time that many students began leaving; some unobtrusively, others with no little regret and apology. One student, Jim, said, "Look, you guys, I'd like to stay, but my dad would kill me." There was no pressure to have these people stay.

I don't think anyone seriously expected our action would persuade the faculty to reverse their decision; but neither did we, as a group, ever relinquish that hope. College demonstrations had already changed policy at other schools.

Soon after dark, an SDS member and former Dartmouth student named John came before the group with a sophomore from the College. The sophomore explained that John was very valuable to the movement and, having been arrested before, would be lost to the cause if given a long jail term. A vote was called to see if John could be excused before police came, but no vote was taken. John would have to make up his own mind. He left. Soon we were down to 56 students, former students, and sympathetic community members. All five of us who were freshmen dormmates remained, along with three other first-year students.

At one point, a student began to remove the U.S. flag from the main hallway flagstaff, but he was stopped. It was agreed to let the flag remain there because our action was not intended to undermine, but to reinforce, the principles for which it was supposed to stand. It remained throughout the occupation.

Don, who had been in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic Convention riots, was afraid that we would encounter the same kind of police brutality that he had encountered there. He argued against a passive surrender to the inevitable arrest, stating that our chances would be better if we used table legs and trash-can lids for our defense and escape. Non-violent argument prevailed, and it was agreed that we would employ passive resistance in the tradition of the civil-rights arrests that had taken place for years in the South.

My guitar was passed around as the hour grew later and the crowd outside thinned. Different people played and sang while we intermittently communicated with school officials through handwritten notes. Food was passed in through a window, and an air of camaraderie began to develop.

That mood recalls for me the frequent criticisms of student activism of that era, that it was motivated not by political conviction but by "adventurism." It was true that we felt adventurous; we were sharing a new experience in resistance to an illegal and immoral national administration, and it created excitement in all of us. But there were simpler ways to have adventures; we were there because we believed in the Tightness of our resistance. We sang, sharing our break with passive tolerance of Dartmouth's military involvement.

Dylan's songs seem trite, even naively old-fashioned to a nation turned in upon itself in a post-war recession. But such words belong no more to one decade than to another. As we sat there in the building, too many people had died; and they kept dying until the men who sent them realized that too many of the living were refusing to cooperate any longer. Dartmouth, however, would continue to cooperate; the State Police were on their way.

The details of the arrival of the troopers, the dogs, the riot-gear, and the vehicles are interesting, perhaps, but they belong in another account. Time magazine did as good a job as any. Time did omit, however, the fact that we had overdone the barricading of the huge double-doors of the administration building early in the day. After the troopers' futile banging away showed that the doors would have to be destroyed for them to gain entry, we removed some of the benches and tables so the doors would give way more handily. We forgot to notify the troopers of our cooperation and on their next heave, they burst through with unexpected ease and tumbled into a heap on the floor. We were not there for combat and we allowed ourselves to be carried away to the waiting buses.

In all but a few cases, the police were civil enough. Don, who had feared police violence, was maced heavily as he was carried struggling from the building. In the process, an over-zealous trooper first delivered a full stream of the excruciating chemical squarely into the face of his commanding officer. Finally, we were all loaded and driven to a nearby armory until our removal to jail.

Our temporary release and subsequent hearing were marked by a number of legal maneuvers most conspicuous for the lack of defense we received from a local law firm. I had occasion to meet with our lawyers at various times, as a part of our group and as a representative of our group, and I do not regret their incompetence; we expected to be found guilty. I do regret that we and the Hanover community paid them several thousand dollars. We soon found ourselves serving 30-day jail sentences for criminal contempt of court, and if the lawyers had a hand in shortening it by three days, it has been a well-kept secret.

MEMORIES of our time in jail are still vivid. I don't know the basis for the particular groupings of students, unless they were random, but we were divided among several county jails throughout New Hampshire. I was in the largest group; the 14 of us spent our hours at Rockingham County Jail talking politics and resistance and doing course work for the spring term. We were allowed, depending upon the particular professors, to finish class assignments from our cells. Some of our group were seniors or graduates and were politically more sophisticated than others; they often led discussion. New ways of resisting the war were debated, as were new lifestyles for those who would graduate or might be dismissed from school. The occupation of Parkhurst was discussed, but it was generally considered over and done.

My journal from those 27 days contains a record of the disturbing hours I spent in these discussions. Such books as Oglesby's Containment and Change, Dumhoffs WhoRules America? and Marcuse's OneDimensional Man were made available to us through faculty members and sympathizers. Clearly, our country was guilty of the imperialism and underhanded dealings of which our State Department accused other nations. And clearly, too, our military policy was often formulated to benefit select financial interests. Even conservatives conceded these things, but they were quick to protest that such exploitation of others was a necessary part of Cold War policy. It is only recently that the undeniably corrupt and illegal activities of government agencies during that time have become public news items. Those who didn't believe it was happening then don't believe it is happening now.

Finally, we returned to campus, and our College Committee on Standing and Conduct hearings began. Some students were suspended because of their radicalism in general and their Parkhurst roles in particular. All of us who were freshman were given one or two semesters' probation but were allowed to continue schooling! Sandy was dismissed from ROTC, and I was not allowed to return to the football team in the fall. (When I went to talk to Coach Bob Blackman about the turn of events, he showed sincere concern for my judgment. "Don't you realize," he asked, "that if you are ever working for a big corporation - say IBM - if you don't conform to their rules, they'll just fire you?" I agreed that yes, they probably would; and I think that as Bob and I looked across his big desk at one another, each realized that the other was operating out of an entirely different play-book. I never played football at Dartmouth again.)

The suspensions of some students had led to the general advice that we plead contrition to the CCSC if we cared to stay in school, but that seemed to me to abdicate a position we were trying to strengthen. I therefore went in with rhetoric blazing, attacking the faculty for "their commitment not to conscience, but to contract." The committee listened patiently, tolerantly, and then asked me if I had anything more to say. I was almost speechless at the lack of concern over my indignation; the meeting was adjourned.

I attribute the committee's benign aspect to the just-concluded testimony of Dean Dickerson, who spoke on my behalf. It was emotionally difficult for him to do so, because his position was radically against that of the demonstrators', and he wanted no confusion about that point. I was not allowed to hear him speak, but his words to the committee carried weight; he ordinarily presided over it. He and I had formed a friendship that lasted, I think, until our last meeting in his office the day before he died in my senior year.

I have never regretted the episode that was Parkhurst '69. Part of who I am now is whatever small courage or abandon it took to join my fellows in that protest against Dartmouth's military cooperation. I have remained active in social and environmental issues and am now pursuing a Ph.D. in education, doing another kind of homework that helps in knowing one's country.

Ours, it seems, hasn't changed much in the past ten years. It has changed some, and for that I am thankful. I am thankful that we are not in a Vietnam war and that we didn't repeat that mistake in defense of the Shah of Iran, as some congressional members advised.

But many more conditions of our national life are very disturbing. While one per cent of the world's richest nation revels in one-third of its wealth, the crushing brutality of city life has become a part of our national status quo. In recent years, the income gap between white and black families has dramatically widened. Despite reported hazards and documented cover- ups, we still pursue a policy of nuclear- power development that risks the safety of millions for still questionable returns. We still outsell in weaponry all other nations of the world combined. Our CIA still actively supports dictatorial regimes in Latin America and abroad. And all the while, the most popular television programming in the country is the most insulting, the most devoid of human dignity.

Our presence in Vietnam has passed, but the time for protest has not; and when voices are raised once again, I hope those of Dartmouth and its graduates will be among them.

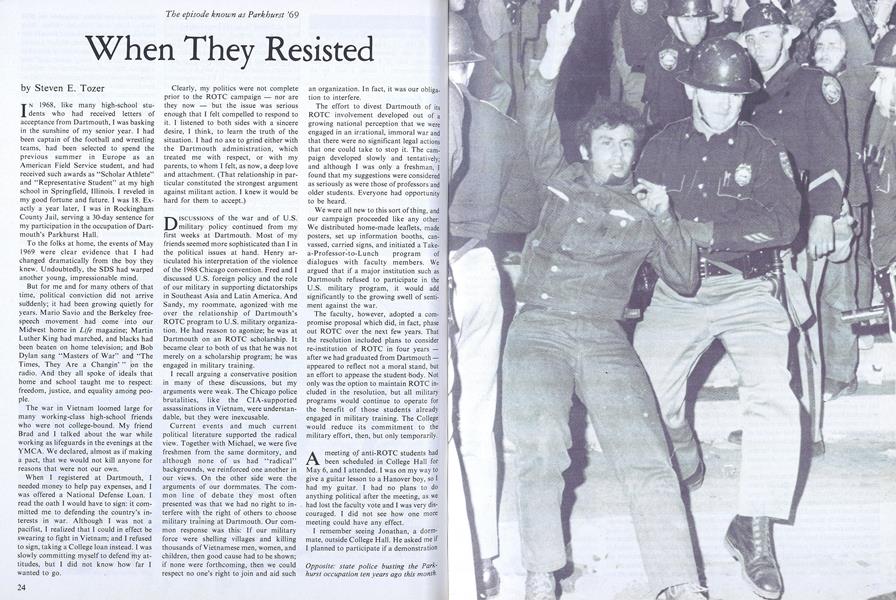

Above: A Parkhurst occupier relaxes overan anti-ROTC banner. On Chase Field ayear earlier (below), another student madeit clear that SDS didn't speak for him.

Amid catcalls and sympathetic peace signs, the arrested students are bused off to jail.

Opposite: state police busting the Park-hurst occupation ten years ago this month.

Steven Tozer '72 is working for his doctorate in education at the University ofIllinois.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureA Three-story House on Bramhall Avenue

May 1979 By Douglas Andrews -

Article

ArticleHearts and Minds Study

May 1979 By TIM TAYLOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

May 1979 By WILLIAM A. CARTER -

Article

ArticleJudicial Clerk

May 1979 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1927

May 1979 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Valedictorian Changes His Mind

MAY 1972 By ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH ALUMNI FUND REPORT

NOVEMBER 1963 By Charles F. Moore, Jr. '25 -

Feature

FeatureThe Cult of Domesticity

SEPTEMBER 1997 By Christine Altieri -

Feature

FeatureOldest Living Graduate, Will Be 100 This Month

APRIL 1964 By Dr. Edwin H. Allen '85 -

Feature

FeatureNative Americans at Dartmouth

MAY 1986 By Peter Mandel -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Beat of Terror

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By STUART A. REID ’08