PRESUMPTUOUS. That's what it was. It was just plain presumptuous for two upstart freshmen to think they could convince the College to shell out bucks for major renovations during a period of increasing financial austerity. And they were so pushy. Always asking for this, demanding that, here a nudge, there a prod. What was the hurry, anyway? Notions about some sort of student center had been kicking around campus for over 50 years, and yet now these guys were hoping to see one open before they graduated. As we say down south, "It'll never fly, Orville."

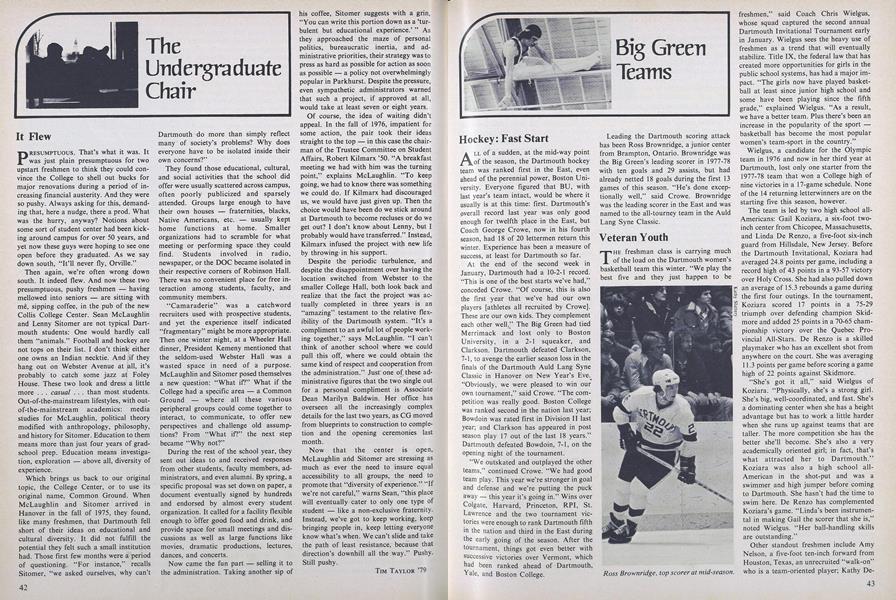

Then again, we're often wrong down south. It indeed flew. And now these two presumptuous, pushy freshmen - having mellowed into seniors - are sitting with me, sipping coffee, in the pub of the new Collis College Center. Sean McLaughlin and Lenny Sitomer are not typical Dartmouth students: One would hardly call them "animals." Football and hockey are not tops on their list. I don't think either one owns an Indian necktie. And if they hang out on Webster Avenue at jail, it's probably to catch some jazz at Foley House. These two look and dress a little more . . . casual . . . than most students. Out-of-the-mainstream lifestyles, with out-of-the-mainstream academics: media studies for McLaughlin, political theory modified with anthropology, philosophy, and history for Sitomer. Education to them means more than just four years of grad-school prep. Education means investigation, exploration - above all, diversity of experience.

Which brings us back to our original topic, the College Center, or to use its original name, Common Ground. When McLaughlin and Sitomer arrived in Hanover in the fall of 1975, they found, like many freshmen, that Dartmouth fell short of their ideas on educational and cultural diversity. It did not fulfill the potential they felt such a small institution had. Those first few months were a period of questioning. "For instance," recalls Sitomer, "we asked ourselves, why can't Dartmouth do more than simply reflect many of society's problems? Why does everyone have to be isolated inside their own concerns?"

They found those educational, cultural, and social activities that the school did offer were usually scattered across campus, often poorly publicized and sparsely attended. Groups large enough to have their own houses - fraternities, blacks, Native Americans, etc. - usually kept home functions at home. Smaller organizations had to scramble for what meeting or performing space they could find. Students involved in radio, newspaper, or the DOC became isolated in their respective corners of Robinson Hall. There was no convenient place for free interaction among students, faculty, and community members.

"Camaraderie" was a catchword recruiters used with prospective students, and yet the experience itself indicated "fragmentary" might be more appropriate. Then one winter night, at a Wheeler Hall dinner, President Kemeny mentioned that the seldom-used Webster Hall was a wasted space in need of a purpose. McLaughlin and Sitomer posed themselves a new question: "What if?" What if the College had a specific area - a Common Ground - where all these various peripheral groups could come together to interact, to communicate, to offer new perspectives and challenge old assump- tions? From "What if?" the next step became "Why not?"

During the rest of the school year, they sent out ideas to and received responses from other students, faculty members, ad- ministrators, and even alumni. By spring, a specific proposal was set down on paper, a document eventually signed by hundreds and endorsed by almost every student organization. It called for a facility flexible enough to offer good food and drink, and provide space for small meetings and discussions as well as large functions like movies, dramatic productions, lectures, dances, and concerts.

Now came the fun part - selling it to the administration. Taking another sip of his coffee, Sitomer suggests with a grin, "You can write this portion down as a 'turbulent but educational experience.' " As they approached the maze of personal politics, bureaucratic inertia, and administrative priorities, their strategy was to press as hard as possible for action as soon as possible - a policy not overwhelmingly popular in Parkhurst. Despite the pressure, even sympathetic administrators warned that such a project, if approved at all, would take at least seven or eight years.

Of course, the idea of waiting didn't appeal. In the fall of 1976, impatient for some action, the pair took their ideas straight to the top - in this case the chairman of the Trustee Committee on Student Affairs, Robert Kilmarx '50. "A breakfast meeting we had with him was the turning point," explains McLaughlin. "To keep going, we had to know there was something we could do. If Kilmarx had discouraged us, we would have just given up. Then the choice would have been do we stick around at Dartmouth to become recluses or do we get out? I don't know about Lenny, but I probably would have transferred." Instead, Kilmarx infused the project with new life by throwing in his support.

Despite the periodic turbulence, and despite the disappointment over having the location switched from Webster to the smaller College Hall, both look back and realize that the fact the project was actually completed in three years is an "amazing" testament to the relative flexibility of the Dartmouth system. "It's a compliment to an awful lot of people working together," says McLaughlin. "I can't think of another school where we could pull this off, where we could obtain the same kind of respect and cooperation from the administration." Just one of these administrative figures that the two single out for a personal compliment is Associate Dean Marilyn Baldwin. Her office has overseen all the increasingly complex details for the last two years, as CG moved from blueprints to construction to completion and the opening ceremonies last month.

Now that the center is open, McLaughlin arid Sitomer are stressing as much as ever the need to insure equal accessibility to all groups, the need to promote that "diversity of experience." "If we're not careful," warns Sean, "this place will eventually cater to only one type of student - like a non-exclusive fraternity. Instead, we've got to keep working, keep bringing people in, keep letting everyone know what's when. We can't slide and take the path of least resistance, because that direction's downhill all the way." Pushy. Still pushy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDr. Hot's Thermal Therapy

January | February 1979 By Bill Galvin -

Feature

FeaturePresident on Trial

January | February 1979 By Marilyn Tobias -

Feature

FeatureThe Old Sod: Summits Above and Graves Below

January | February 1979 By Ann Lloyd McLane -

Feature

FeatureWomensports

January | February 1979 -

Article

ArticleWriter Possessed

January | February 1979 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

January | February 1979 By DAVID R. BOLDT