In the 14th chapter of The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck writes some powerful words. He writes that despite wars, despite the falling bombs, despite death, despite the folly into which man from time to time plunges himself, these very horrors are the proof that man's spirit has indeed taken a step forward, a step perhaps hard fought and small, but a step nevertheless. He tells us "This you may say and know it and know it":

If the step were not being taken [Steinbeck continues], if the stumbling-forward ache were not alive, the bombs would not fall, the throats would not be cut. Fear the time when the bombs stop falling while the bombers live — for every bomb is proof that the spirit has not died. And fear the time when the strikes stop while the great owners live — for every little beaten strike is proof that the step is being taken.

Many will find it disturbing that I quote such words in a magazine connected with an institution like Dartmouth College. I assume Steinbeck is not terribly popular within our "family." I mean, after all, the man was a socialist. And just look at what he writes! Even if one takes such unsettling images as sliced throats and falling bombs for metaphors, the passage still contains at its core an affirmation of dissension, of strife, of struggle; a belief that what little progress we can manage down here will come through a never-ending process of questioning old assumptions and testing new ideas. Fear the time the mind submits to complacent stagnation. Fear the time man becomes calcified into a fixed and rigid existence.

How do we respond to such a stern and unyielding injunction? What relevance do these words have for this college safely entrenched upon its hill? Even if such an ideal of rigorous self-interrogation is impossible to attain, emphasis on questioning and controversy should lie at the very heart of a liberal arts education. It seems to me that a college could do no better than to graduate individuals intelligently equipped with the critical ability to challenge the. status quo in whatever field they enter - individuals willing not only to accept change but to implement it. The atmosphere on campus that can best facilitate this process is one that encourages cultural and intellectual diversity. This calls for students (and faculty) drawn from both sexes, all races, different nationalities, and varied political, economic, and religious backgrounds. Anything less means the Dartmouth graduate is poorly educated.

Naturally, not everyone agrees. I was talking with a friend of mine, a junior at the College, about the recent furor over fraternities and minorities. Pontificating in my usual manner, I launched into a discussion of the notions described above — asserting that the controversy and the thrashing out of conflicting viewpoints is healthy for the school; they demonstrate we still care enough to argue. My friend (maybe I should downgrade that to "acquaintance") countered by saying, no, he had dispensed with "all those ideas" way back in high school, and now he only wanted four years of placidity and peace of mind, a nice quiet staircase to law school or business school or whatever. I find it distressing, to say the least, that at the advanced age of 20 anyone could have cut through the ambiguity in the world and completely settled his mind on all those troublesome little problems like sexism, racism, discrimination, and so forth.

Unfortunately, this student is not atypical at Dartmouth. When I speak with other friends about the ills they discern in this school, the usual topics like rowdyism, drunkenness, and anti-intellectualism often arise. But the problem most consistently stressed is the homogeneity of the student body — the overwhelming pressure to conform that breeds, at best, an insensitivity to alternate perspectives, and at worst, a bitter hostility toward anyone presumptious enough to question even timidly the prevailing values. I am embarrassed and ashamed of the number of times I've read in The Dartmouth a column or letter applying "malcontent" or "do-gooder" or some such term to anyone speaking out on problems such as the abuse of women, discrimination against blacks, or insults to Native Americans. In other words, an individual is not criticized for, say, his inaccurate assessment of a situation or his erroneous conclusions; he is derided for the mere act of questioning, for the mere fact of being different. When Homo sapiens first arrived on the evolutionary scene, they probably got a similar reception from those Neanderthals still hanging around the neighborhood who didn't appreciate the change, but one would think that after roughly 35,000 years things would have improved.

Perhaps such resistance to change is understandable in an institution that rallies around the slogan, "Lest the old traditions fail." Although Richard Hovey may have wished to encourage our fidelity to certain enduring educational values, his words today are too often invoked merely as a defense of what has been against what could be. Certainly, maintaining a sense of continuity with the past is important, but not when it blinds us to the critical needs of the present and future. If this school is indeed committed to providing the leaders of tomorrow, why not instead have for a theme: "Lest the new initiatives fail"? Why not instead urge an acknowledgement of and response to the realities of the 20th century?

I apologize if I sound bitter about my Dartmouth experience. I am not. In fact, I have many fond memories of the sort admissions officers love to have us relate to prospective students. I find extremely encouraging the many significant changes I've seen at Dartmouth since my arrival in the fall of 1975: the recent commitment to end quotas for women; the increasing sensitivity toward minorities; the appearance of social alternatives to fraternities; and the promise of a forum for cultural diversity inherent in the new College Center. But after my own internal struggle — after considering all the pros and cons, yeas and nays, pushes and pulls — I finally conclude that if today a high school senior asked me if he or she should matriculate at Dartmouth, my answer would be no. It hurts me to write that, but at this point I believe anyone seeking what I describe above as a comprehensive education (as opposed to just finding a good job) would do better to attend another institution, probably one outside the Ivy League, probably a state university. Fortunately, there is hope — hope that the College will continue to improve at its recent rate, hope that the alumni will not resist that change but encourage it, and hope that in five years I can enthusiastically reverse my judgment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

FeatureE – i – e – i – o

June 1979 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

FeatureExit with a Flourish

June 1979 By Beverly Foster -

Feature

FeatureEncouraging growth, affirming the educational process

June 1979 By Robert Kilmarx -

Article

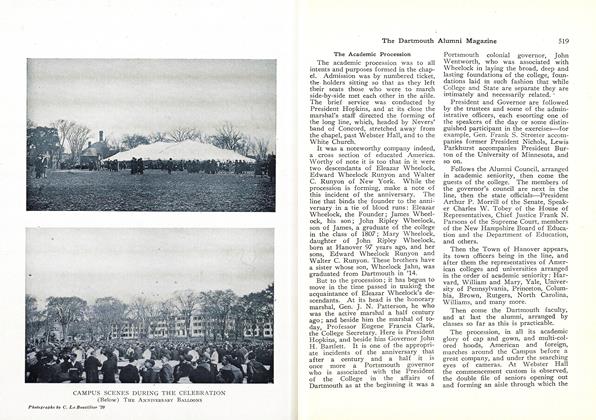

ArticleCommencement

June 1979 By James L. Farley -

Article

Article'Radical' with a Cause

June 1979 By Tim Taylor

TIM TAYLOR '79

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH COLLEGE REPRINTS

December, 1919 -

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR BARTLETT PREPARES GUIDE TO HANOVER

DECEMBER 1926 -

Article

ArticleThayer Overseers

MAY 1972 -

Article

ArticleOTHER WINTER SPORTS

APRIL 1973 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Secrets Leak Out

November 1934 By C. E. W. '30 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in Manhattan

December 1951 By STAN JONES '18