SUBJECT: The recent moratorium on classes called to discuss complaints of racism and sexism at the College. Problem: How to explain the situation without sounding like a preacher.

The moratorium was called at the end of a week and a half of increasingly tense racial confrontations. Though I think the specific incidents building up to the protests were over-blown, the larger problems they stood for were not.

Two Indian-clad students skating out on the hockey ice I can pass off as an immature act that deserves no more than an official reprimand. After all, freedom of expression means just that, the freedom to present ideas and prejudices no matter how distasteful or Neanderthal. But the incident symbolized something larger. It pointed up a long-standing attitude of a large part of the student body that might be characterized as "militant insensitivity." By this I mean that after all the word- smoke has cleared over what the Indian symbol does or does not mean, its desirability or lack thereof, two statements seem to emerge loud and clear: One portion of the student body has stated, "The symbol is offensive and degrading"; another portion has answered, "We don't give a damn."

In other words, the moratorium was not needed because of the irresponsible actions of two students, or because a Building and Grounds crew dismantled the Afro- American snow sculpture, or because a group of frustrated students took to spray- painting an already half-melted block of ice on the Green. Rather, the problem lies with years of non-communication among students, years of insensitivity - both active and passive - between the various factions of a badly splintered Dartmouth community.

The meeting in Webster Hall began calmly enough, with pleas from President Kemeny for tolerance and understanding. Kemeny characteristically cautioned that no issue is black and white. "Listen," he suggested. "Communicate," he urged. As I was nodding my silent agreement, Judy Aronson '82 took the platform as the representative for her organization, Women at Dartmouth. The contrast with Kemeny's well-modulated speech was startling. Beginning emotionally and growing more so, Aronson delivered a blistering attack on what she described as a deeply ingrained sexism within this institution - from the lopsided male/female ratio, to the lack of women in administrative and tenured positions, to the alleged sexual harassment of students by professors - and concluded with a list of demands for improving the status of all women at Dartmouth.

The speeches that followed - by representatives from the Latino Forum, Afro-American Society, and Native Americans at Dartmouth - unfolded in much the same way: electrically charged expressions of pain and anger, accusations of individual and institutional racism, demands for certain reforms. Usually, emotion won out over rationality, realistic description gave way to hyperbole. For instance, James DeFrantz '79, president of the Afro-American Society, characterized a black's existence at Dartmouth as a "living hell." But I found it difficult to condemn too readily such excesses. Here were people who had been silent for years over second-class treatment, finally erupting with righteous indignation - a state of mind notoriously hard to argue with.

After all was over that day, for me one Damoclean question still loomed up above: What will the alumni think? The answer is, of course, I don't know. But I do know a few things I hope the alumni do not think.

I hope they don't think that expressions of discontent are restricted to a few maladjusted, "sour-grapes" individuals. We sometimes hold a sentimental conception of Mother Dartmouth as one big happy family, singing around the campfire, just bubbling over with camaraderie. Fine. That image is indeed a part of the Dartmouth experience, including my own. But beneath that placid facade is a more complex, more painful, more real situation. The real Dartmouth includes women who are disgusted at the harassment and abuse they have suffered at their own school. It includes a depressing amount of voluntary segregation of races. It includes Native Americans who are specially recruited and then repeatedly subjected to the callous flaunting of a demeaning stereotype.

But women, blacks, and Native Americans are only the most visible dissenters. I myself am a WASP - one from the group supposedly on top, a happy oppressor as it were. But ever since I was a freshman, I have wavered between disillusionment and amused resignation at all those negative points usually brought up about Dartmouth - the anti- intellectualism, insensitivity, rowdiness, etc. Though I once feared I was just a wistful discontent left out of all the fun, I now realize the majority of people here share a similar dissatisfaction. Corner almost any seemingly jocular, well-adjusted student away from all the Dartmouth rah-rah for a while, slip past the usual conversational defenses, and you will probably find a person confused and uncertain about the social situation, one who might express a concern over widespread alcoholism, or perhaps question the intense pressure to conform, or maybe admit that male smash- up-the-frat virility is not so great.

The point is that those critical of Dartmouth are not just troublemakers crying out in the wilderness of left field. The portrait of a fractured community presented last month is accurate, whether we like to admit it or not. And that is why the response that I have already heard once and expect to hear again - "If you don't like it, get out" - is so infuriatingly narrow-minded. If everyone did get out, there wouldn't be many left. And those speaking out often care the most.

My none-too-subtle aim here has been to counsel restraint and reason. If I didn't succeed in keeping out the preacher, sorry. But it seems imperative to me that the past graduates of Dartmouth understand the problems the current students are facing. Instead of vigorous denials, defenses of the alma mater, and counter-accusations, how about considering that even if the complaining voices are a bit strident, they are at least sincere, the complaints themselves are about very real problems, and the requests not unreasonable at all? As Professor Bill Cook pointed out in his closing remarks in Webster Hall, the College has already committed itself in official policy to fulfilling almost all of the demands presented. It is not asking too much to keep those commitments.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThere and Back Again

April 1979 By John S. Major -

Feature

FeaturePilgrims' Progress

April 1979 By L. Bruce Anderson, Edward Bradley -

Feature

FeatureA winter of discontent, a day of perceiving differences

April 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleJust Out of Reach

April 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

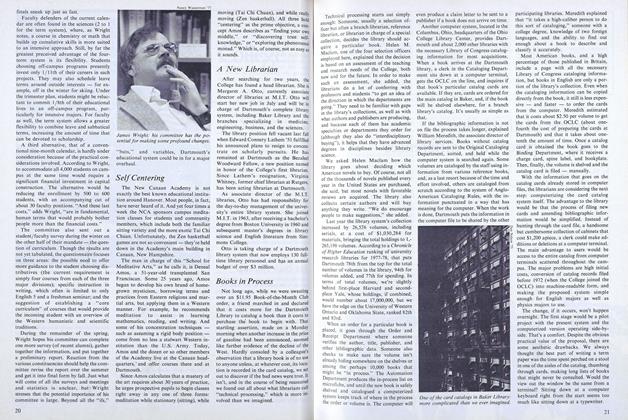

ArticleBooks in Process

April 1979 -

Article

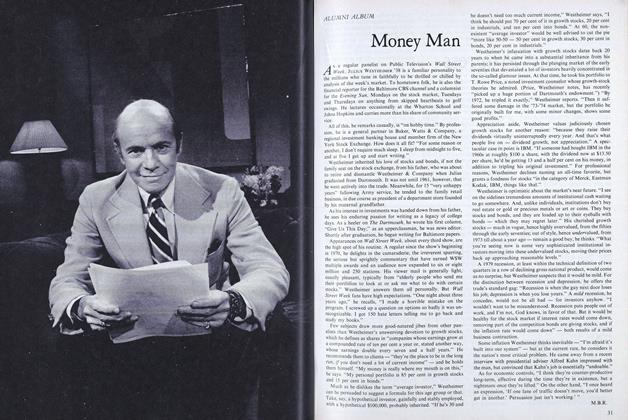

ArticleMoney Man

April 1979 By M.B.R.

TIM TAYLOR '79

Article

-

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR SHAW LEAVES FACULTY TO GO TO KNOX COLLEGE

April 1920 -

Article

ArticleFRESHMEN SHOW IMPROVED SCHOLASTIC RECORDS

March 1921 -

Article

ArticleTWO RECENT MASSACHUSETTS APPOINTMENTS

January, 1925 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

February 1977 -

Article

ArticleHALF WAY THERE

December 1990 -

Article

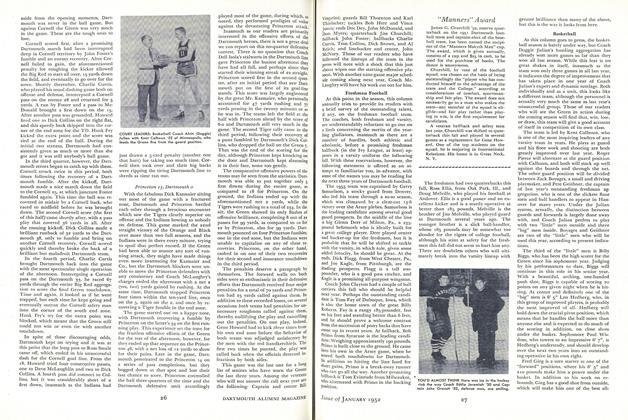

ArticleFreshman Football

January 1952 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26