BRITISH AMBASSADOR TO THE UNITED STATES

PROFESSOR TOYNBEE and others warn us that each civilization is judged by its ability or inability to find an active and dynamic response to the challenges of its time. How would our countries rate on this basis? In these dangerous times the penalties may be high if any of us, Canada, United States or Britain, become too irremediably committed to wrong courses.

First, what are the underlying trends which must condition our thinking about the issues before us? Secondly, how are our peoples adapting themselves to those trends at my corner of the North-American triangle?. . .

Let me apply the tests which I have suggested to three of the more obvious threats of the modern world. The first is the drive towards responsible self-government within the borders of a nation-state which we know as nationalism. The second is the speed of scientific development which can open up a new world for man. The third is the impact of weapons of mass destruction which make it unlikely that our present form of civilization could survive their use in another war. For the first time in the history of man it is becoming open to all to enjoy a high standard of living and leisure. Equally for the first time it is becoming possible for man to wipe himself from off the face ol the earth.

These are wide questions, and others will answer them for the United States and Canada. But may I put to you my view of how my own country, Britain, has been doing since the war to meet these three challenges.

What is our answer to the challenge of nationalism? There are some solid historical reasons why our answers here tonight can be clear and unequivocal.

It was in Britain that the concept of representative selfgovernment within the borders of the nation-state was born. It was in Canada and the United States that the idea was made applicable to vast continental areas and multi-national groups through the Federal system. It is in our Common wealth of Nations that it has reached a special form of collective development.

These ideas and institutions have been among our great contributions to political philosophy. They have exercised a profound influence upon those who have led nationalist movements everywhere and at all times whether they acknowledge their ideological debts to us or not. They may not be our exclusive invention. But they are certainly not Communist "inventions" and they certainly rank with our greatest exports.

Today many so-called nationalist leaders continue to accuse us of "imperialism." Imperialism is a difficult word to define; but if "anti-imperialism" is a movement to give responsible self-government to groups of the same nationality, then it should be honestly and frankly recognized that we originated the movement, that we equipped it with its basic theories and institutions, that we have provided a training ground for its leaders of all creeds and colors, and that we have fostered it for generations as a government, as a civilization and as a people. No empire or government or ad- ministration in history has trained once subject peoples more carefully in the arts of responsible national self-government or handed over power to them more extensively and generously. . . .

It is in the context of technology that the British people today confront the second historic force in the modern world to which I referred: the opening up of a new world of human development in terms of power, scientific achievement and industrial and agricultural production. For us, adjustment to this new world is not merely a field for adventure and profit, but a basic fact of life which determines our survival as a nation. We live precariously under compulsions which do not always operate on nations more self-sufficient than Britain.

Let us consider some of these compulsions and their impact upon Britain.

r t First, the need for exports. For us it is literally true that we must export or die, because we must import or die. We cannot raise on our island enough food to feed our population, nor enough raw materials to feed our industries and keep employed one of the most highly skilled labor forces in the world. Every year we must produce a substantial surplus in our balance of trade to pay for this food and raw materials, to liquidate old debts and to finance new investments overseas. We can only sell this surplus if our exports are competitive in quality and in price. Moreover, they must be competitive by a margin sufficiently large to overcome tariffs and other obstructive trade barriers raised against our goods.

To achieve this requires continually new techniques, new inventions and industrial innovations, not only to reduce the cost of production but open up new markets and maintain old ones. It requires a continuous adaptation of our export industries to the constantly changing pattern of international trade....

Secondly, we have the compulsion which derives from the need for power to drive the wheels of our industry. Coal is still our main source of power, and we have still large reserves. But we have been mining coal so extensively and so long that it becomes yearly more expensive to extract. We must find new sources of power. We do not have oil. We do not have cheap water power. It is not therefore a modernistic luxury, but a necessity for us to have nuclear power stations throughout the country as soon as possible. . . .

The third basic trend to which we must adjust our lives and our policies today derives from the existence in our hands and in hostile arsenals of weapons of mass destruction so powerful that civilization might not be able to survive their use. ... What adjustment must we make to bring up to date our international institutions and alliances and our national policies? What is the significance of the developments of specific defense policies for our basic objective of deterring aggression?

Any defense policy today cannot be a unilateral affair. Defense against the dangers which confront us today involves units too large to be confined within any national boundaries. No one country today, not even the United States, has within its boundaries or under its sovereign control all the raw materials, all the bases, all the launching sites, all the industrial resources, the weapons and the means of delivering them, which it needs to defend itself against an all-out attack by the Communist powers. In terms of defense, neutralism and isolationism have become military absurdities. And the Soviet claim to possess the inter-continental ballistic missile makes this more rather than less true. Nor does any theory of limited nuclear warfare change this. We are either united or we are defenseless. The bonds which unite Britain, Canada and the United States are not just bonds of blood or of ideology or of sentiment. They are bonds of mutual selfinterest in survival.

The Communists know that. They know that if they can stimulate allied disunity and dissension, they have a weapon far more destructive than any inter-continental missile. . . . Upon our ability to resist divisive maneuvers and remain united depends our power to deter aggression and to prevent war.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

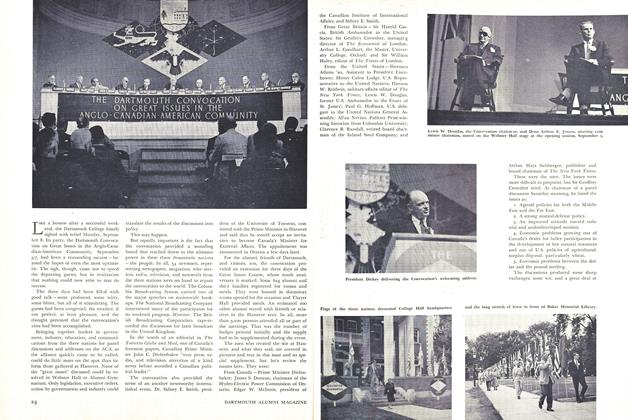

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTenure

April 1975 -

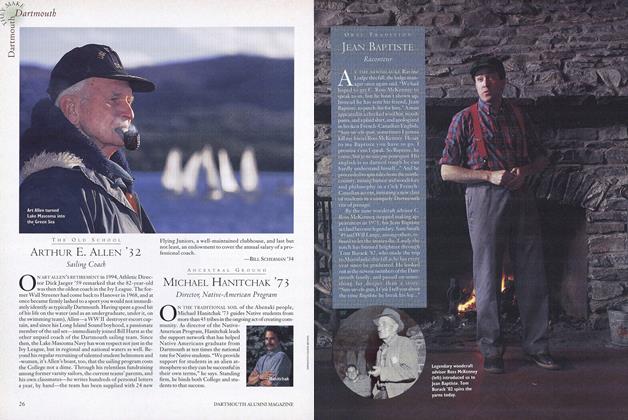

Cover Story

Cover StoryJean Baptiste

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureWhy Teachers Teach

January 1957 By ANDREW G. TRUXAL -

Cover Story

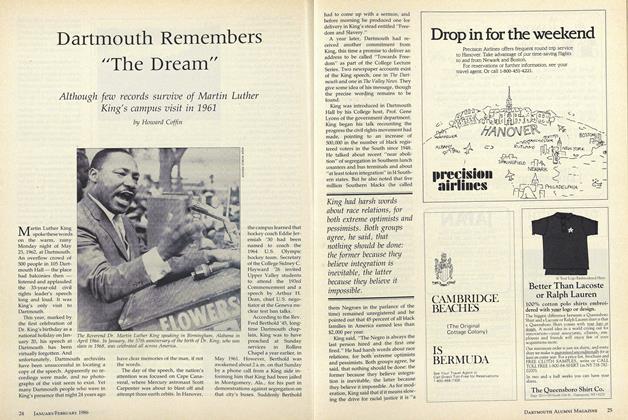

Cover StoryDartmouth Remembers "The Dream"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Howard Coffin -

Feature

FeatureRisky Business

Mar/Apr 2001 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

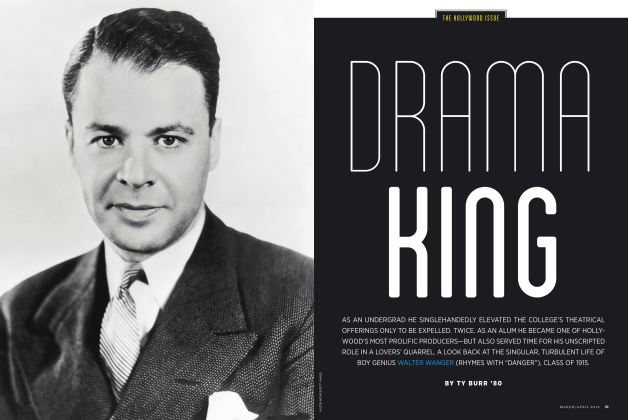

Feature

FeatureDrama King

MARCH | APRIL By TY BURR ’80