AT the conclusion of the first intermission of the February 25 hockey game, two students appeared on the ice painted and dressed as "Dartmouth Indians." After a few turns around the rink, they retreated to a waiting car and were driven away. Their actions, they later explained, were intended to "increase school spirit" and, by some definition of that phrase, they succeeded beyond their wildest expectations.

The significance of the "skaters incident" can be understood well only in the context of Dartmouth. To some, it seemed to imply a thumbed nose to those who have for the past decade supported a number of changes at the College - co-education, year-round operation, de-emphasis of fraternities, and last (and in many ways least) the discontinuation of the unofficial school "mascot." To others, the event - and its enthusiastic initial reception by some members of the crowd - signified a sense of frustration and loss; to them, it seemed that the years of painstaking explanation as to why an ethnic caricature might be offensive to a considerable and growing segment of the Dartmouth community had been wasted.

"There were hard feelings on all sides during the days after the hockey game; students and staff whose sentiments placed them at odds over the issue and who consequently felt betrayed and confused looked to the administration of the College for leadership and direction. Even the eventual resolution of the problem proved to be controversial and upsetting to some. But no one can deny that the action of the skaters did indeed raise the spirits of the College. They served as a catalySt for discussions, sometimes heated, sometimes abstract, of a variety of topics by a wide assortment of people. Some had previously conversed rarely with one another; few had heard what the other was saying. This process culminated in a day of open forums (March 8) in which the College paused from its normal business to take stock and pay attention to its own internal harmony. Only time will tell how successful we all were. One person's perspective, my own, follows.

It is never altogether agreeable to realize that progress and social change are expensive. The re-examination of assumed or even cherished ideas is often a painful and disturbing process for all concerned. "Growing pains" are a reality both for the individual and for the community, but they can't, and shouldn't, be avoided; dynamism is not just necessary to life - it is life.

The many disturbing and confusing events of the past weeks are perceived by some as a kind of showdown between two forces: the mythic, ponderous and, for many, demonstrably successful "Old Dartmouth," and the upstart, untested and evolving "New." Unfortunately, this division is often believed to separate irrevocably those identified with one position from those defined in the other. In the bizarre realm of stereotypes, "Old Dartmouth," composed of a coalition of faceless alumni, white male fraternity members, and people who like to have "fun," defends Civilization-As-We-Know-It against a rowdy band of allied women, minorities, and humorless bleeding-hearts.

The significant truth missed in this hasty analysis, however, is the obvious fact that if the latter group did not believe in the basic values of the College, did not see, or wish to see, their own futures bound together with that of their chosen institution, they would be elsewhere. It is safe to say, therefore, that all sides, despite various and disparate disappointments and disenchantments, do share a common denominator: the faith and the conviction that Dartmouth College can and should be something quite fine.

Nothing suggests this more than the two events which framed what was for most of us a troubling week. The skaters and their vocal and less-vocal supporters sought to "renew school spirit" by publicly recreating a mascot which for some years (but not for many, when the facts are examined) was an uncontested source of identification for many members of the community. The ensuing events, if nothing else, prove one thing: that times have changed, perhaps much more so than anyone formerly believed.

Five days later, another kind of demonstration, equally public, took place on the center of the Green. A diverse coalition of people joined hands and sang to proclaim that they, too, were members of the Dartmouth community and that they, too, demanded an institution in which they could find pride and spirit.

It seems clear that the majority of people involved in each event meant no specific insult or defamation to others. In their way they were both affirming kinds of protestations. But hurt, misunderstanding, and alienation seemed to result. Some people believed that each demonstration particularly excluded them and their aspirations from full participation in this community, regardless of their retrospectively explained (in the case of the first) or announced (in the second) intentions. The gap between them, I'm convinced, is one of empathy, not ideology.

The time has come for all members of the Dartmouth community to accept some basic facts; for a number of years the "Indian symbol" has had, for its proponents, very little to do with Native Americans and very much emphasis on "symbol." It has become a symbol of a symbol, the banner of those who question a variety of changes which have taken place in the last decade. That's all fine and good except for one very real thing: The use of an ethnic caricature truly offends and abuses Native American and other members of this community - and that's no abstraction. The history of the College regarding Indians (14 graduates in the first 200 years) is not such that it permits license with the name or visage (especially a distorted, stereotyped, and inaccurate one) of a contemporary population which has suffered and in many areas continues to experience neglect, oppression, and misrepresentation. It is this "tradition," and no other, which the symbol evokes for Native Americans.

The days of the casual acceptance of notions such as the Happy Rhythmic Negro, the Nefarious Money-lending Jew, the Passive Dumb Woman and, yes, the Savage/Noble Indian are done. That other institutions may for a while continue their use in no way makes it permissible in our kind of community. So let's literally and figuratively "bury the hatchet" once and for all.

Let us rather take this unique opportunity to listen to each other, to acknowledge our common concerns and to respect our differences. This will be neither easy nor uncomplicated, and no one of us will be happy with each proposed direction, but we've all paid a high price for this moment in our time together - let's not waste it. With a spirit of understanding and mutuality, a really "New" Dartmouth, built on the very best of past traditions and the best of innovative ideas, can be vigorously sought together.

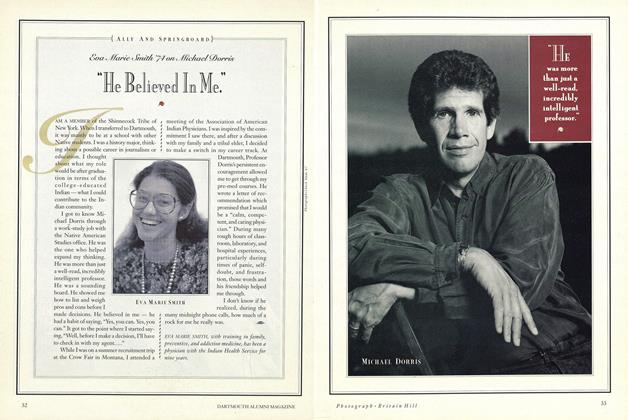

Michael Dorris, a Modoc, is assistant professor of anthropologyand chairs the Native American Studies program.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThere and Back Again

April 1979 By John S. Major -

Feature

FeaturePilgrims' Progress

April 1979 By L. Bruce Anderson, Edward Bradley -

Feature

FeatureA winter of discontent, a day of perceiving differences

April 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleJust Out of Reach

April 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleBooks in Process

April 1979 -

Article

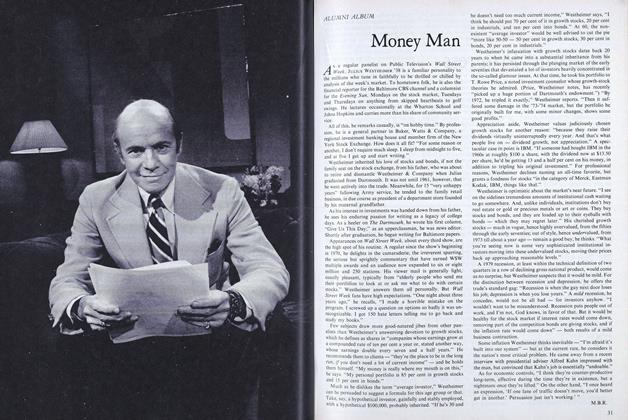

ArticleMoney Man

April 1979 By M.B.R.