WHILE the likelihood of a Dartmouth club of Shanghai reactivated in time for a June luncheon seems remote indeed, there remains on mainland China, as far as we know, a small cadre of Dartmouth alumni.

Scant word of former Chinese undergraduates has reached Hanover since the Bamboo Curtain descended in 1949; as far as can be learned, no American-born alumni remained, either voluntarily or involuntarily, after the Communists came to power. For the most part, the news has been that there was no news.

Francis Pan '26, who lives in Hong Kong, had not at last report heard from his brother Quentin '24 since 1966, and then only after an 11-year silence. Quentin, formerly a dean and professor at Tsing Hua University in Peking, had been demoted to a minor research job at the National Minorities Institute for being unbecomingly popular with students. His welfare was "a constant source of anxiety," Francis wrote.

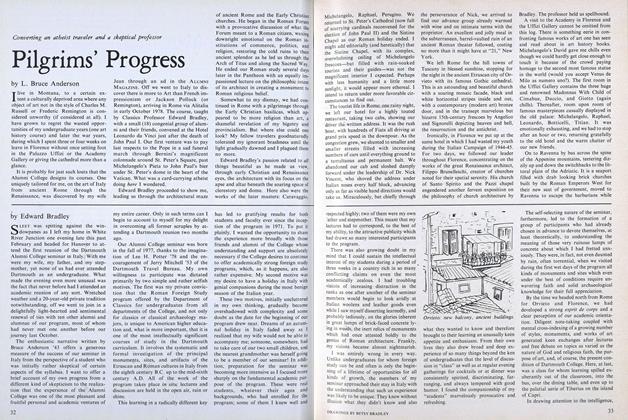

Another Chinese alumnus emerged briefly and unexpectedly in 1972, when former Dartmouth Professor Jonathan Mirsky visited China with a group of Far East scholars. At the same National Minorities Institute, Mirsky encountered Wen-Tsao Wu '25, a Columbia Ph.D. and reputedly China's foremost sociologist. "When I mentioned that I was from Dartmouth College," Mirsky recalled, "I didn't expect that anyone would have heard of it. Imagine my surprise when it turned out that Dr. Wu had spent four years here as an undergraduate. Like all Dartmouth men, he appears to have total recall of the College and its surroundings, and his memories were typically enthusiastic." Wu and Mirsky are shown together above.

The 1940 directory lists 29 alumni then living in China; the 1955 edition adds two more, while at least one other Chinese student had matriculated meanwhile. Eight of the 14 Americans known to be in China shortly before World War II are still living, all of them in this country. Some of them were interned by the Japanese after Pearl Harbor and later repatriated. None has apparently been in contact with Chinese alumni since his return following the Communist takeover.

Of the 15 Chinese listed in the 1940 directory, Francis Pan and Hsi-Jui Shen '28 have been in Hong Kong for many years. Fen-Min Tung '27, a judge in Shanghai in pre-Communist days, was there until he retired in 1969, when he asked the College to suspend his mail pending a new address; there has been no word since. Another, Lin-Yi Ho ' 11, retired after the Communists came to power, but remained in Shanghai until 1961, when he was granted a temporary permit to travel to Hong Kong on a sad errand involving the death of his American son. Because of bureaucratic delays, his permit expired before his business was done, and he could neither return home nor receive permanent-resident status in Hong Kong. Under a special American program, he came to California to live with his daughter.

Among the others, one, George Chang '30 of the Central News Agency of China, died in Tokyo in 1958; three, Po Chen '14, Shao-Kuang Yu '26, and Kyung-Pang Yeu '27, are on some evidence presumed dead. The rest, including until recently Wen Tsao Wu, have been reluctantly classified by Alumni Records as "lost." Of the younger men, Peter Ling '51 returned to China following his junior year; Chung-Nim Lam '55 left after one year, finished medical school in Peking in 1957, took post-graduate training in Scotland, and died in Canada in .1976; and Shih-Yueh Wang '44 died in Hong Kong the same year. Wang's two daughters, Elizabeth and Hilda, are currently enrolled as Dartmouth undergraduates.

In addition to the nostalgic Professor Wu, the elusive alumni include Hua Huang '18, who graduated Phi Beta Kappa, went on to Harvard Law School, and entered diplomatic service; Nien-Tsung (Horatio) Chen '24, who transferred to the University of Michigan to study municipal government; Ssu-Yung Liang '26, a distinguished archaeologist and a member of the Chinese equivalent of the French Academy; Quentin Pan, apparently too liberal to retain a high position; Chojen Chen '31, a banker also alleged to have been demoted for insufficiently pure ideology; and Theodore Tisheng Yen '35, whose father was pre-war minister to Washington. It was thought for a time that Hua Huang had been rediscovered - as ambassador to Canada. But investigation revealed that Ambassador Huang was born in 1913. Had they been one and the same, the Dartmouth Huang would have graduated from the College, a trifle too precociously, at the age of five.

By no coincidence, the Chinese students were, almost to a man, graduates of Tsing Hua University, long since absorbed by Peking University. As Lo-Yi Ho has explained, Tsing Hua was established on the American junior-college model specifically to prepare Chinese students for higher education in this country. As secretary of the university and senior-class adviser, Ho wrote, "Twice I had charge of the students all the way to the U.S., and it afforded me an opportunity to visit colleges and universities. Each time I included Dartmouth in my tour, and I still remember my visit to President Hopkins."

A similar old-world paternalism flavors a letter to President Hopkins from Minister Yen, who dispatched an attache from the legation to escort his son to college. "I am anxious," wrote the father, "for him to see the best of American college life, and prefer for him to live in a dormitory. ... It may be well for him to have a certain amount of coaching in subjects wherein he may be deficient, as for instance French, in which I desire to have him learn well. ... I am enclosing a cheque for $500, which after paying for his tuition and other fees may be handed to him for his personal expenses. ... While there is no need for my son to stint himself as to expenses, I am not at all in favor of his spending extravagantly during his college days. .. if

It remains for Lin-Yi Ho, writing to his classmates in 1966, to describe most poignantly the turbulent times that have intervened between the aristocratic assumptions of Yen the father and the stern egalitarianism that has isolated Yen the son from the Western World for more than four decades. "If there is anything that I can boast of and brag about, it is that I have lived and survived perhaps under more different forms and kinds of government than any other classmate," he wrote. Born in 1888, when China was an absolute monarchy, he lived successively under a Republic, a dictatorship, foreign occupation, "the dying years of Nationalist China," and Communist rule. "Thus I have come back once again to the land of the free," he concluded, "after all the misfortunes and losses, trials and tribulations, stress and strain, first in a war-torn country suffering from internal strife and external aggression throughout my active life, then in a reign of terror, and finally in a colony where everybody was a VIP - master and boss, even the humblest clerk in the government bureaucracy. Like an imprisoned bird out of the cage with an individuality and the freedom of a human being, free from mental distress and torture, I enjoy and treasure the peace and happiness which goes with freedom."

Francis Pan might have been writing of all the alumni in China during those years when he responded to an inquiry about one of them: "He is not lost but just out of reach."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

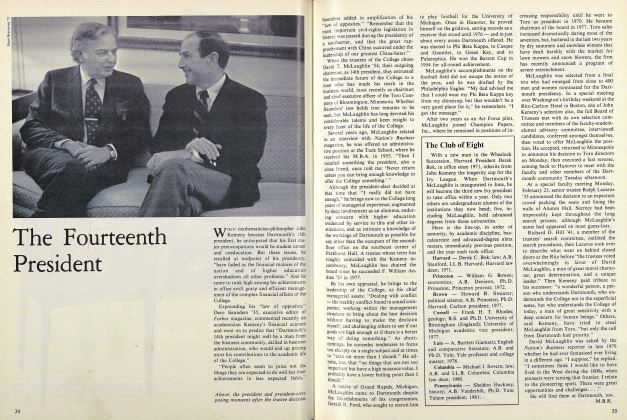

FeatureThere and Back Again

April 1979 By John S. Major -

Feature

FeaturePilgrims' Progress

April 1979 By L. Bruce Anderson, Edward Bradley -

Feature

FeatureA winter of discontent, a day of perceiving differences

April 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleBooks in Process

April 1979 -

Article

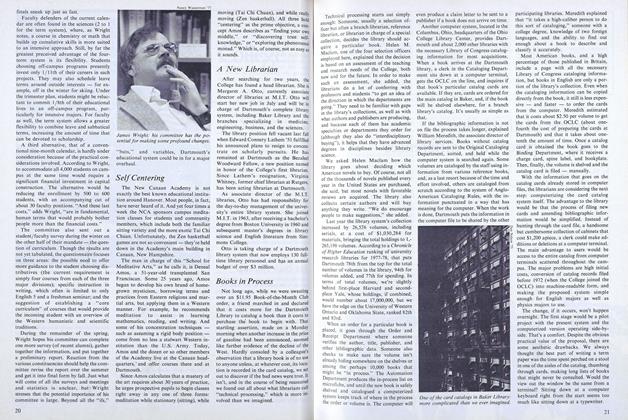

ArticleMoney Man

April 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleOn the Raising of Spirits

April 1979 By MICHAEL DORRIS

M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleVisitor of the Month

November 1941 -

Article

ArticleSecond Trustee Term For Harvey P. Hood

July 1950 -

Article

ArticleSenior Fellows

November 1957 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

November 1946 By John H. Minnich '29 -

Article

ArticleAuthor and Sophomore

March 1961 By TED BREMBLE '56 -

Article

ArticleWah-Hoo-Wah!

October 1941 By The Editor