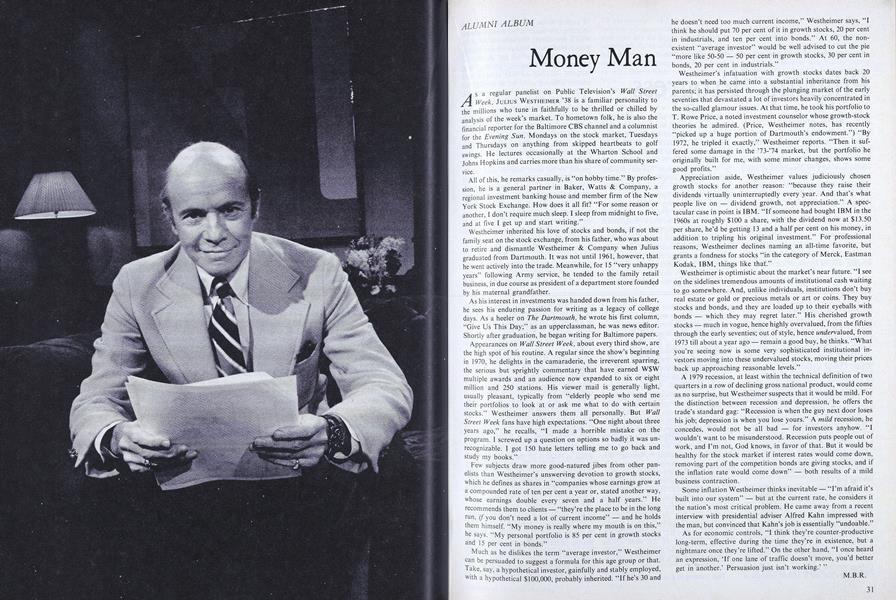

As a regular panelist on Public Television's Wall Street Week, JULIUS WESTHEIMER '38 is a familiar personality to the millions who tune in faithfully to be thrilled or chilled by analysis of the week's market. To hometown folk, he is also the financial reporter for the Baltimore CBS channel and a columnist for the Evening Sun, Mondays on the stock market, Tuesdays and Thursdays on anything from skipped heartbeats to golf swings. He lectures occasionally at the Wharton School and Johns Hopkins and carries more than his share of community service.

All of this, he remarks casually, is "on hobby time." By profession, he is a general partner in Baker, Watts & Company, a regional investment banking house and member firm of the New York Stock Exchange. How does it all fit? "For some reason or another, I don't require much sleep. I sleep from midnight to five, and at five I get up and start writing."

Westheimer inherited his love of stocks and bonds, if not the family seat on the stock exchange, from his father, who was about to retire and dismantle Westheimer & Company when Julius graduated from Dartmouth. It was not until 1961, however, that he went actively into the trade. Meanwhile, for 15 "very unhappy years" following Army service, he tended to the family retail business, in due course as president of a department store founded by his maternal grandfather.

As his interest in investments was handed down from his father, he sees his enduring passion for writing as a legacy of college days. As a heeler on The Dartmouth, he wrote his first column, "Give Us This Day;" as an upperclassman, he was news editor. Shortly after graduation, he began writing for Baltimore papers.

Appearances on Wall Street Week, about every third show, are the high spot of his routine. A regular since the show's beginning in 1970, he delights in the camaraderie, the irreverent sparring, the serious but sprightly commentary that have earned W$W multiple awards and an audience now expanded to six or eight million and 250 stations. His viewer mail is generally light, usually pleasant, typically from "elderly people who send me their portfolios to look at or ask me what to do with certain stocks." Westheimer answers them all personally. But WallStreet Week fans have high expectations. "One night about three years ago," he recalls, "I made a horrible mistake on the program. I screwed up a question on options so badly it was unrecognizable. I got 150 hate letters telling me to go back and study my books."

Few subjects draw more good-natured jibes from other panelists than Westheimer's unswerving devotion to growth stocks, which he defines as shares in "companies whose earnings grow at a compounded rate of ten per cent a year or, stated another way, whose earnings double every seven and a half years." He recommends them to clients - "they're the place to be in the long run, if you don't need a lot of current income" - and he holds them himself. "My money is really where my mouth is on this,' he says. "My personal portfolio is 85 per cent in growth stocks and 15 per cent in bonds."

Much as he dislikes the term "average investor," Westheimer can be persuaded to suggest a formula for this age group or that. Take, say, a hypothetical investor, gainfully and stably employed, with a hypothetical $100,000, probably inherited. "If he's 30 and he doesn't need too much current income," Westheimer says, "I think he should put 70 per cent of it in growth stocks, 20 per cent in industrials, and ten per cent into bonds." At 60, the non-existent "average investor" would be well advised to cut the pie "more like 50-50 - 50 per cent in growth stocks, 30 per cent in bonds, 20 per cent in industrials."

Westheimer's infatuation with growth stocks dates back 20 years to when he came into a substantial inheritance from his parents; it has persisted through the plunging market of the early seventies that devastated a lot of investors heavily concentrated in the so-called glamour issues. At that time, he took his portfolio to T. Rowe Price, a noted investment counselor whose growth-stock theories he admired. (Price, Westheimer notes, has recently "picked up a huge portion of Dartmouth's endowment.") "By 1972, he tripled it exactly," Westheimer reports. "Then it suffered some damage in the '73-'74 market, but the portfolio he originally built for me, with some minor changes, shows some good profits."

Appreciation aside, Westheimer values judiciously chosen growth stocks for another reason: "because they raise their dividends virtually uninterruptedly every year. And that's what people live on - dividend growth, not appreciation." A spectacular case in point is IBM. "If someone had bought IBM in the 1960s at roughly $100 a share, with the dividend now at $13.50 per share, he'd be getting 13 and a half per cent on his money, in addition to tripling his original investment." For professional reasons, Westheimer declines naming an all-time favorite, but grants a fondness for stocks "in the category of Merck, Eastman Kodak, IBM, things like that."

Westheimer is optimistic about the market's near future. "I see on the sidelines tremendous amounts of institutional cash waiting to go somewhere. And, unlike individuals, institutions don't buy real estate or gold or precious metals or art or coins. They buy stocks and bonds, and they are loaded up to their eyeballs with bonds - which they may regret later." His cherished growth stocks - much in vogue, hence highly overvalued, from the fifties through the early seventies; out of style, hence undervalued, from 1973 till about a year ago - remain a good buy, he thinks. "What you're seeing now is some very sophisticated institutional investors moving into these undervalued stocks, moving their prices back up approaching reasonable levels."

A 1979 recession, at least within the technical definition of two quarters in a row of declining gross national product, would come as no surprise, but Westheimer suspects that it would be mild. For the distinction between recession and depression, he offers the trade's standard gag: "Recession is when the guy next door loses his job; depression is when you lose yours." A mild recession, he concedes, would not be all bad - for investors anyhow. "I wouldn't want to be misunderstood. Recession puts people out of work, and I'm not, God knows, in favor of that. But it would be healthy for the stock market if interest rates would come down, removing part of the competition bonds are giving stocks, and if the inflation rate would come down" - both results of a mild business contraction.

Some inflation Westheimer thinks inevitable - "I'm afraid it's built into our system" - but at the current rate, he considers it the nation's most critical problem. He came away from a recent interview with presidential adviser Alfred Kahn impressed with the man, but convinced that Kahn's job is essentially "undoable."

As for economic controls, "I think they're counter-productive long-term, effective during the time they're in existence, but a nightmare once they're lifted." On the other hand, "I once heard an expression, 'lf one lane of traffic doesn't move, you'd better get in another.' Persuasion just isn't working.' "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThere and Back Again

April 1979 By John S. Major -

Feature

FeaturePilgrims' Progress

April 1979 By L. Bruce Anderson, Edward Bradley -

Feature

FeatureA winter of discontent, a day of perceiving differences

April 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleJust Out of Reach

April 1979 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleBooks in Process

April 1979 -

Article

ArticleOn the Raising of Spirits

April 1979 By MICHAEL DORRIS