Shortly after his arrival at Dartmouth in 1932, Mexican artist Jose Clemente Orozco wrote to President Hopkins explaining his proposal for a mural in the basement of Baker Library:

The American continental races are now becoming aware of their own personality as it emerges from two cultural currents - the indigenous and the European.

The great American myth of Quetzalcoatl is a living one embracing both elements and pointing clearly, by its prophetic nature, to the responsibility shared equally by the two Americas of creating here an authentic New World civilization.

I feel that this subject has a special significance for an institution such as Dartmouth College which has its origin in a continental rather than in a local outlook - the foundation of Dartmouth, I understand predating the foundation of the United States

The proposal, of course, became reality - a reality sometimes ignored by those who have no occasion to visit the reserve corridor, and often taken for granted by those who do. Last month, more than a few of both types squeezed into the corridor's west end to hear a panel discussion on what has become Dartmouth's most famous - some would say most infamous - artwork.

The event marked the visit to Hanover of Carlos Fuentes, a novelist, short-story writer, essayist, playwright, one of Latin America's foremost literary figures, and one of Mexico's leading leftist intellectuals. The 50-year-old Fuentes, who grew up the son of a career diplomat, has always been active in political circles, including as ambassador to France from 1975 to 1977. Fuentes' fiction, as does Orozco's art, draws much of its material from Mexico's revolution of 1910, often criticizing the modern state for failing to uphold the ideas of those early days.

Sara Castro-Klaren, associate professor of Romance Languages, opened the program by placing the work of both Fuentes and Orozco within the context of the cultural explosion following the revolution. Both artists deal not so much with individuals, but with the movement of people and the struggle of masses - "self-identity articulated in a universal framework."

Retired Professor Churchill Lathrop recalls that even before Orozco arrived in Hanover, the Art Department had sponsored three shows of his work between 1929 and 1931. Originally, the artist was to have demonstrated his mural painting in the small corridor linking Baker with the Carpenter Galleries, and, if funds could be obtained, completed a larger work inside Carpenter, probably on the myth of Daedalus. The plans were enlarged and moved to the reserve corridor after Orozco enthusiastically discovered its large blank walls. Financing the project was a major problem in those early Depression years, but one finally solved by hiring Orozco as an assistant professor of art for two years. The understanding was, Lathrop said, that his teaching would be visual instead of verbal, with the painting done in public.

Fuentes also discussed the murals, especially stressing the co-mingling of European and indigenous civilization after the conquest of Cortez. "Utopia," said Fuentes - the word of Thomas More brought by Spanish missionaries - linked together the spirit of the Renaissance with the golden age of Quetzalcoatl. The ensuing conflict of cultures has been Mexico's richest historical asset, embodied in the murals as the "desire for power and the power of desire."

Turning again to the revolution, Fuentes concluded his talk with an anecdote: In the summer of 1915, when the forces of Emiliano Zapata captured Mexico City, the troops were billeted in the houses seized from the aristocracy. Never before having seen such wealth, they were especially fascinated by the full-length mirrors and stood gazing at themselves for days. For these Indians, explained Fuentes, their culture was in their bodies - in their manner of greeting or moving or walking. For the first time they could actually see the embodiment of that culture. "As they huddled and looked at themselves in the mirrors, they were able to say, 'Look! It is I. Look! It is you.' Finally, 'Look! It is we.' It is this same mirror that is reflected in the great Orozco murals that we are all admiring today."

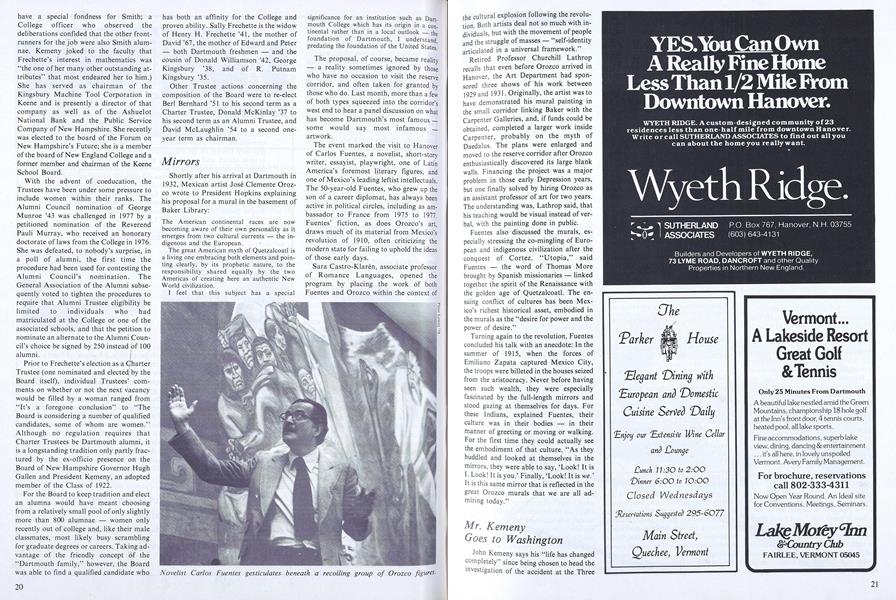

Novelist Carlos Fuentes gesticulates beneath a recoiling group of Orozco figures.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

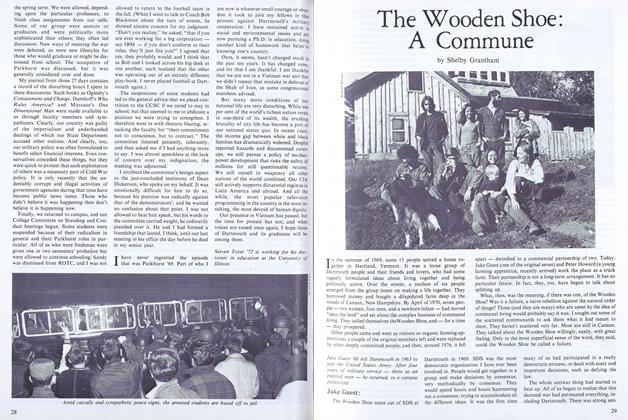

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

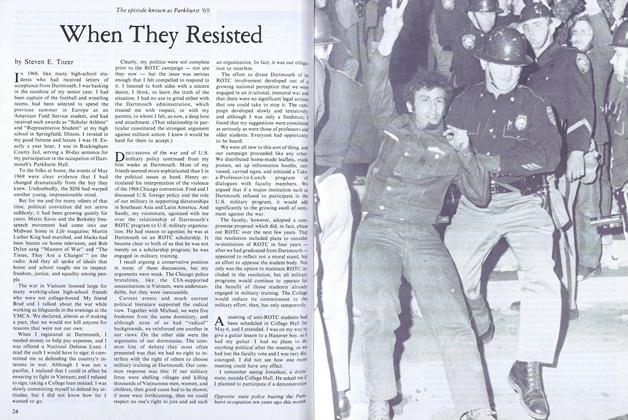

FeatureWhen They Resisted

May 1979 By Steven E. Tozer -

Feature

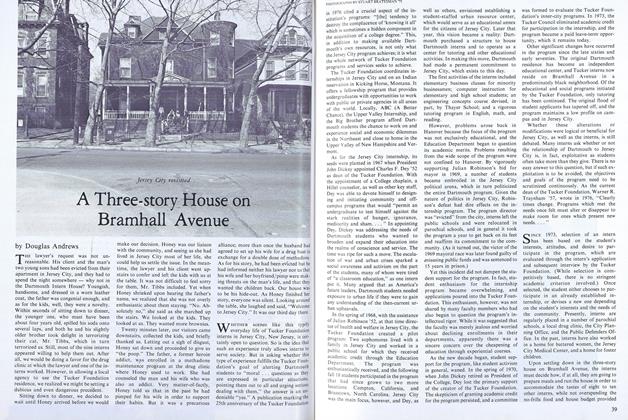

FeatureA Three-story House on Bramhall Avenue

May 1979 By Douglas Andrews -

Article

ArticleHearts and Minds Study

May 1979 By TIM TAYLOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

May 1979 By WILLIAM A. CARTER -

Article

ArticleJudicial Clerk

May 1979 By M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

Article$5000 LEFT FOR INCREASE IN FACULTY PAYROLL

December 1921 -

Article

ArticlePresident Heard at Luncheon

June 1935 -

Article

ArticleCornell Tickets

October 1938 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER UNDER COVER

FEBRUARY 1964 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleCHARLES MERRILL HOUGH, A GREAT JURIST

JUNE, 1927 By Judge William N. Cohen '79 -

Article

ArticleFrom a 1908 Mem Book

April1935 By L. W. G