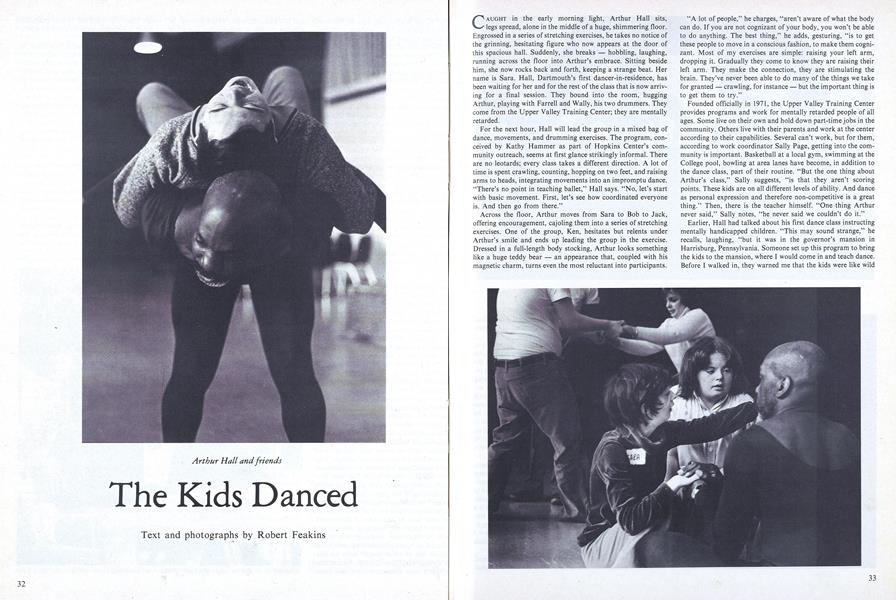

Caught in the early morning light, Arthur Hall sits, legs spread, alone in the middle of a huge, shimmering floor. Engrossed in a series of stretching exercises, he takes no notice of the grinning, hesitating figure who now appears at the door of this spacious hall. Suddenly, she breaks — hobbling, laughing, running across the floor into Arthur's embrace. Sitting beside him, she now rocks back and forth, keeping a strange beat. Her name is Sara. Hall, Dartmouth's first dancer-in-residence, has been waiting for her and for the rest of the class that is now arriving for a final session. They bound into the room, hugging Arthur, playing with Farrell and Wally, his two drummers. They come from the Upper Valley Training Center; they are mentally retarded.

For the next hour, Hall will lead the group in a mixed bag of dance, movements, and drumming exercises. The program, conceived by Kathy Hammer as part of Hopkins Center's community outreach, seems at first glance strikingly informal. There are no leotards; every class takes a different direction. A lot of time is spent crawling, counting, hopping on two feet, and raising arms to heads, integrating movements into an impromptu dance. "There's no point in teaching ballet," Hall says. "No, let's start with basic movement. First, let's see how coordinated everyone is. And then go from there."

Across the floor, Arthur moves from Sara to Bob to Jack, offering encouragement, cajoling them into a series of stretching exercises. One of the group, Ken, hesitates but relents under Arthur's smile and ends up leading the group in the exercise. Dressed in a full-length body stocking, Arthur looks something like a huge teddy bear — an appearance that, coupled with his magnetic charm, turns even the most reluctant into participants.

"A lot of people," he charges, "aren't aware of what the body can do. If you are not cognizant of your body, you won't be able to do anything. The best thing," he adds, gesturing, "is to get these people to move in a conscious fashion, to make them cognizant. Most of my exercises are simple: raising your left arm, dropping it. Gradually they come to know they are raising their left arm. They make the connection, they are stimulating the brain. They've never been able to do many of the things we take for granted - crawling, for instance - but the important thing is to get them to try."

Founded officially in 1971, the Upper Valley Training Center provides programs and work for mentally retarded people of all ages. Some live on their own and hold down part-time jobs in the community. Others live with their parents and work at the center according to their capabilities. Several can't work, but for them, according to work coordinator Sally Page, getting into the community is important. Basketball at a local gym, swimming at the College pool, bowling at area lanes have become, in addition to the dance class, part of their routine. "But the one thing about Arthur's class," Sally suggests, "is that they aren't scoring points. These kids are on all different levels of ability. And dance as personal expression and therefore non-competitive is a great thing." Then, there is the teacher himself. "One thing Arthur never said," Sally notes, "he never said we couldn't do it."

Earlier, Hall had talked about his first dance class instructing mentally handicapped children. "This may sound strange," he recalls, laughing, "but it was in the governor's mansion in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Someone set up this program to bring the kids to the mansion, where I would come in and teach dance. Before I walked in, they warned me that the kids were like wild animals." He found that was sheer nonsense, that if anything, "We both seemed to relate better to the movements of the body than any of the political or academic disciplines."

Shouting encouragement at Ken, putting his arm around Sara, trading jokes with Jack, Arthur convinces the group to meet his demands, demonstrating the motivating force that makes the sessions so electric. Born in Memphis, Tennessee, he became interested in dance when he was a child. As a black male growing up in the thirties, he remembers, he was not particularly encouraged with his dancing. After some time with the National Negro Opera Company, a stint in the Army (where he became the first black choreographer), then more dance training, he founded the Arthur Hall Afro-American Dance Ensemble in Philadelphia in 1970. A member of the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, Hall is also president of the Ile Ife Museum in Philadelphia, which collects, preserves, interprets, and exhibits Afro-American works of art.

It is his commitment to West African dance that is at the basis of Hall's instruction. Throughout the session with the training center class, every movement seems to key into clapping or counting with the best of the drums, and everyone gets a chance to bang away at them. Arthur is adamant about their importance. "In West African dance, the drummer is making you. There is a marriage that happens when you put your foot down to that rhythm or beat. West African dance is just gut; you're feeling it. The drum beat makes you aware. It measures every movement I have these kids do, and remember - what we are trying to teach them is an awareness of the body."

Hall points with special pride to Ken, a boy who had been, both at the training center and in early dance classes, non-verbal. As the sessions continued, he had become increasingly animated, by now to the point that he is talking and counting along with the others. Admitting this, Sally Page adds that "Ken had never, prior to this class with Arthur, jumped with both feet in the air. And he can crawl now, too. I've tried to figure out why he responded so well, and I think it's because dance is so primitive and so is Ken."

Sally walks over to the corner and asks Tom if he wants to join the others. He refuses. For most of the sessions, he has seemed glued to the spot next to the drummers. But at the end of this, their last class, he too joins in the group's final dance — gliding across the floor as Arthur leads them in a slow-motion exercise.

"The story," Hall explains, "is how much can I pass on to you without talking. So we come back to what I was saying before. They have to be made aware of their bodies. They are physically uneducated and, when the drum beats, when we clap and move, they are revealing something to themselves. The beat measures the movement. They think, 'Oh, yes, this is my hand, and I am moving it to my head while my legs are going here.' " He sighs and, raising his arms in the air, says, "Listen, all this clapping and counting — it's simply infectious."

Throughout the ten-week program, the class has caused considerable interest, and the last day is no different. Over by the doorway, several strangers peek in; members of the Hopkins Center staff occasionally peer from office windows overlooking the hall. The group seemed unaware of the attention until, one day, a local television crew showed up, causing one of the group to comment aloud, "Oh, oh, they're gonna put us on TV again." Sally Page says of all the observers: "They seem to want to do what we are doing. They often see us in town and sometimes even here at Hopkins Center, but in this class, it has been different. I think they have learned something about us. We're really a friendly bunch, and when someone like Arthur Hall, who isn't afraid of us, comes along and gets us going, we accomplish everything he asks of us."

In a circle on the floor, they all sit together as their last moments with Arthur draw to a close. There is talk of going some day to Philadelphia to visit him. Jack cracks everyone up by saying he will bring his wife. But it now seems a possibility to him. Two weeks later, at the training center, Sally Page says the group can still remember that Arthur will be back at Dartmouth in 1980. "It's remarkable," she comments, "that they can still remember that."

After that last class, Arthur describes his sessions with the group as "a program of passion." Staring intently, he says, "Dance is feeling, passion. We could try to teach ballet; we could try to teach that discipline. Heck, I love ballet, but here that isn't the point." He pauses, then continues. "I'm really talking about breaking down barriers. We're trying to free these kids. I'm still freeing myself. People say we don't have time for programs like this. I don't like that. Give it a chance." A smile crosses his face. "Give it a dance."

One of the class put it even better when, back at the training center two weeks later, she stood up in front of the group. "When I dance, I ...," she hesitated, then found her thought, "... I felt together with feelings and movements." Then she started to dance, remembering what Arthur Hall taught her.

Arthur Hall and friends

Robert Feakins '78 spent last year working as an undergraduateintern at Hopkins Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUps and Downs in the Big Leagues

September 1979 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Article

ArticleThe Bard's American Friend

September 1979 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

September 1979 By JOHN L. GILLESPIE, Fred Alpert '54 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

September 1979 By WILLIAM B. CATER JR. -

Article

ArticleCarving Out Spaces

September 1979 By Beth Baron '80

Features

-

Feature

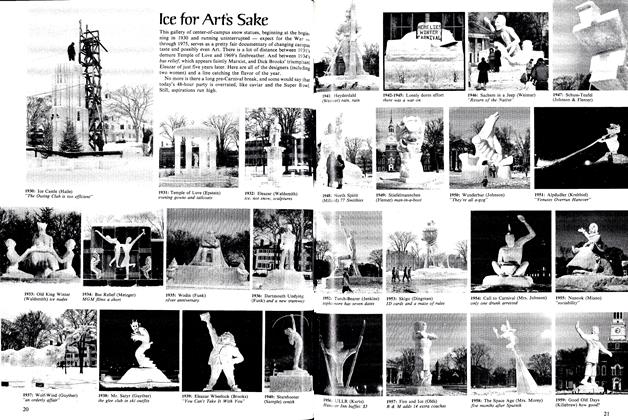

FeatureIce for Arťs Sake

February 1976 -

Cover Story

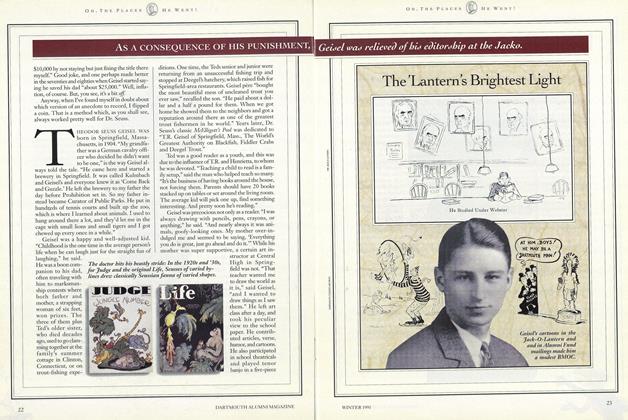

Cover StoryThe 'Lanterns' Brightest Light

December 1991 -

FEATURE

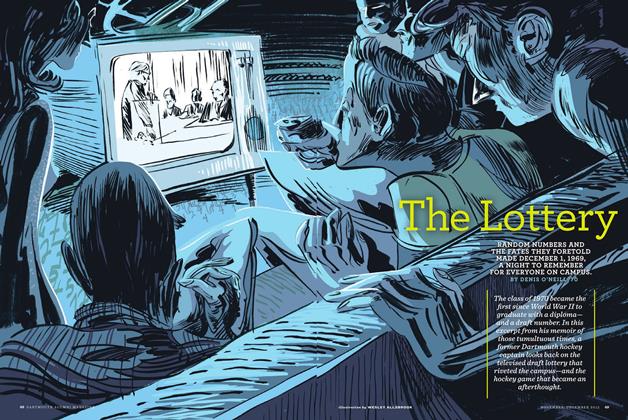

FEATUREThe Lottery

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By DENIS O’NEILL ’70 -

Feature

FeatureFive Plays for All Seasons

September 1975 By DREW TALLMAN and JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

FeatureThe Last of the Liberals?

May 1981 By Frank B. Wilderson -

Feature

Feature"The Computer Revolution" Revisited

OCTOBER 1984 By George O'Connell