David Kastan, assistant professor of English and a marathon runner, was on his way one morning to the Epsom ten- miler. He was studying in England late last summer, and the Epsom ten-miler was to be his first appearance in a British race. Kastan hadn't considered that the Epsom race might not be in Epsom. So, of course, he got off the train there. When he asked someone in Epsom if there was anywhere he could perhaps change into his running gear, he was told there most certainly was. There was, that is, six miles down the road in Tottenham Corners, where the Epsom ten-miler would be starting.

Not easily discouraged, Kastan, who runs the marathon in two hours and 40 minutes, inquired about bus service between Epsom and Tottenham Corners. To his delight, he learned that there was indeed a bus which ran between the two towns — but the bus had left for Tottenham Corners some ten minutes earlier.

"I stuck my thumb out into the road with my running gear and shoes draped over my arm," he related recently, "and about ten seconds later, a car pulled up." This Samaritan of lost runners asked Kastan if he was going to the race. "I said 'Yes,' and my driver introduced himself as Laurie O'Hara. He turned out to be the best English runner in the over-40 age division. In fact, he still holds the world record in that age group for the 10,000 meters. We drove to the race, and I'd known Laurie by then for all of the ten minutes it took us to get to Tottenham Corners. We were getting out of the car, and Laurie said, 'Come, I'll introduce you to some of the lads.' We walked over to where some runners were warming up, and Laurie announced, 'This is my American friend, Dave.' Well, that sort of became my name: 'Laurie's American friend, Dave.' While I was warming up, everyone whom I had met was coming up to introduce other runners to me: 'Oh, this is Laurie's American friend, Dave.' Within 20 minutes, I knew almost 100 runners in Britain."

Kastan came straight to Dartmouth in the fall of 1973 from his graduate studies at the University of Chicago. A Shakespeare scholar, Kastan recalled that "coming from Chicago intellectually was really quite a change. To leave the incredibly charged University of Chicago campus, and to come to Hanover where there is a much more low-key, genteel approach to learning, was a bit of a shock at first."

Kastan joked that his first scholarly endeavor at Dartmouth involved a rereading of the college motto, Voxclamantis in deserto — "a voice crying in the wilderness." "When I first got here I thought it was wonderful to hear at Dartmouth a voice crying in the wilderness. But I discovered that sometimes Dartmouth is a wilderness without a voice. I was a little surprised in some ways at the tone of the place, and in some ways, I'm delighted by it. There's a kind of generosity, and decency, and openness that's very attractive. On the other hand, the lack of intensity sometimes is disturbing."

Many students and recent graduates who have struggled under the pressures created by the Dartmouth Plan's short academic terms would be quick to challenge Kastan's assertion that Dartmouth lacks intensity. But he maintains he does not mean to imply that Dartmouth students don't work hard. "The students are academically excellent, but not intellectually involved," he said. "I have students who are very willing to work hard to get A's, to get good recommendations, to get into good law schools, but the motivation is an external motivation. Dartmouth becomes a way of establishing credentials to do something else, instead of a place where students work out of a desire to master material for the love of that material."

Kastan jokingly compared the Dartmouth experience to a bar mitzvah, the celebration of a Jewish boy's entrance into manhood. "Of course," he said, "the bar mitzvah is a fraud in some ways; at age 13 the Jewish boy does not become a man. Dartmouth's celebration of the transition from adolescence into adulthood is similar. At the end of four years, we tell you that today you become an adult. This is a fraud in the same way as the bar mitzvah. Students come out of Dartmouth with their degrees, come out with their admissions to law or medical schools, come out with their jobs at Procter and Gamble. I'm not sure that's exactly what Dartmouth should do."

What does Kastan see as the purpose of a Dartmouth education? "Our graduates ought to be able to assume useful roles in the society, but if those roles really are to be useful, it's going to be because the people in those roles know not only how to think, but maybe why to think. Somehow we've got to teach critical thinking and intellectual sympathy."

Why has Kastan chosen to teach Shakespeare's plays? His first lecture to his classes addresses the question, "Why do we bother to read Shakespeare at all?" He begins the answer by quoting from the editors' introduction to the first folio, published in 1623: "Reade him, therefore; and againe, and againe: And if you do not like him, surely you are in some manifest danger, not to understand him." Kastan continues: "Not to understand Shakespeare is not merely to miss wonderful entertainment; it's to cut ourselves off from a powerful source of knowledge, knowledge of the vital terms of our own humanity, knowledge that might generate the intellectual and emotional sympathy that, in turn, might refine the moral intelligence so that we are able to live to our fullest humanity and not barbarize the lives of those around us, or our own. In the first chorus of 'The Rock,' T. S. Eliot asks, 'Where is the knowledge we have lost with information?' I think it's in Shakespeare, and that's why we should read him."

Kastan credits the University of Chicago's David Bevington ("the best teacher I've ever had") for providing him with an example of how one might help to generate that moral and intellectual sympathy. In his lectures, Kastan uses throwaway lines, pantomime, references to movies like Woody Allen's Manhattan and Neil Simon's The Goodbye Girl, along with jokes that might somehow juxtapose the Boston Red Sox and Shakespeare. "Rather than being a way of evading the material," he explained, "I think it's a way of suggesting the possibility for Shakespeare to infiltrate other areas of life, to suggest that somehow Shakespeare makes a difference outside 13 Carpenter Hall."

Kastan argues that the best courses are like time bombs — that is, what they impart becomes most important sometime after the final exams have all been graded. His greatest hope for his students, as a professor, is that perhaps something that they remember from the study of Shakespeare's plays will help them to understand some of life's problems or pleasures, such as a failing marriage or an extraordinary friendship. "That's why I teach. I'm sure not in it for the money, and I'm not in it for the good hours. But thinking about the plays has helped me to understand lots of things about my own life. Shakespeare certainly should never become, at least in the classroom, a pretext for talking about one's own emotional and moral life. But it's a remarkably fertile context for that discussion."

Perhaps there's some coincidence that a professor whose specialty is Shakespeare also heads the College's judiciary body, the College Committee on Standing and Conduct (CCSC). In the dean's office they often joke that David Kastan "belongs" to the CCSC. "I love that line," Kastan said. "That 'belongs' is just the perfect verb there. They've got me."

Why does Kastan agree to chair the most time-consuming committee at Dartmouth? "I know it's enormously time- consuming, and often frustrating, and often very disturbing. But the pleasures come from that shared dialogue about moral issues. I find it really exciting to listen to ten different members of this community reason through a problem. That problem might be dropping a fourth course after a deadline, which raises interesting pedagological questions, or it might be the problem of what to do about dorm damage."

Kastan and his fellow committee members find it embarrassing to tell people that serving on the CCSC is fun. "To say that it's fun always conjures up the vision of the committee taking hideous, sadistic pleasure in the difficulties of students. On the contrary, it's often very painful to listen to students' problems. Each committee has a unique character and imposes that character on the campus. That's what finally justifies in my mind the time I put in on it. The CCSC makes a difference to what Dartmouth College is like, and it's a college that I care about enormously." His evidence for this claim: "When we play Princeton [his alma mater] in sports, I root for Dartmouth."

As much time as Kastan's academic and committee work consumes, he never fails to find the time to run every day — often twice: six and a half miles in the morning, and ten to 13 miles in the afternoon. "I'll be working at my desk thinking about a lecture or an article I'm writing, and I sort of hit that dead point in my day. It's probably hypoglycemia, but whatever the reason, I find I'm not working efficiently. So, I'll go run."

He claims that his reason for running is probably narcissism, but he's not absolutely sure. He rejects popular attempts, like Dr. George Sheehan's, to mystify running. He says he fears that creating a mystique about running might discourage people from trying it. "It leads people to expect these wonderful intellectual and emotional experiences from running. They go running, and they're hurting just trying to make it around the track, and they're mumbling to themselves, 'Where's the high? Where's the high?' I think the high is stopping."

What does Kastan think about when he runs? "The time I spend running tends to be the time I reserve to think about running. Otherwise, I'd think about running all the time. I have a real fear about that. I'm always afraid that if somebody woke me up in the middle of the night, shined a light in my eyes, and said, 'Okay, Kastan, what are you?' I'm not sure what I'd say. Would I say I'm a Dartmouth professor? An American? I don't know. I'm afraid I'd say that I'm a runner."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUps and Downs in the Big Leagues

September 1979 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

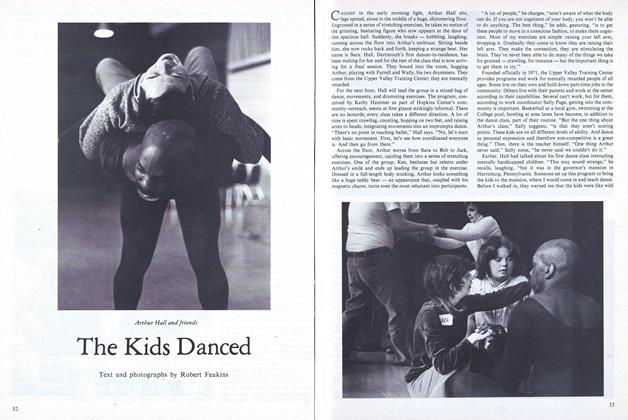

FeatureThe Kids Danced

September 1979 By Robert Feakins -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

September 1979 By JOHN L. GILLESPIE, Fred Alpert '54 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

September 1979 By WILLIAM B. CATER JR. -

Article

ArticleCarving Out Spaces

September 1979 By Beth Baron '80

Michael Colacchio '80

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Beth Ann Baron '80, Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleZombie of the 1902 Room

October 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleAn Old-fashioned Mutant

December 1979 By MICHAEL COLACCHIO '80 -

Article

ArticleThe Great Society

April 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Books

BooksExperiential Education

OCTOBER 1981 By Michael Colacchio '80

Article

-

Article

ArticleEARLY SCHOOLS FOR GIRLS IN HANOVER

May 1918 -

Article

ArticleChemistry Assistant

January 1943 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

October 1933 By Bill McCarter '19. -

Article

ArticleGreen Jottings

October 1955 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleNippee-Tuckee-Caloosahatchee

December 1975 By MILTON TUCKER '19 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29