Margaret Otto, the College's new head librarian, says that although at first she had her doubts about leaving M.I.T. and the bright lights of Boston for the hills of New Hampshire, when she checked out Dartmouth she found that the place has its own attractions, the most pleasantly surprising of which was alumni interest in the libraries "something I never saw'at M.I.T."

She was delighted, too, to find that Dartmouth's administration, faculty, and students are also unusually supportive of their libraries, and she had high praise for Dartmouth's foresight in starting early to take advantage of technological advances in library science. "No," she said winningly, "I don't miss the city at all. Dartmouth College is a very exciting place for a librarian to be just now."

"How come?" we asked with pointed naivete, whereupon Otto whisked us off to a computer terminal in the Reference Department and arranged an on-line, or immediate, bibliographic search for us.

"What would you like to know about?" she asked matter-of-factly, as if it weren't the grandest question in the world. "Oh, gee," we fumbled. "Human sexual differences, maybe?" Five minutes later we had a computer print-out informing us that there are 9,491 works in the Dartmouth College libraries dealing with that subject.

Did we want abstracts of all of them? Or would we like to pinpoint our investigation somewhat? Overwhelmed by the thought of 9,491 abstracts on any subject, we opted to pinpoint. Asking the computer to cross- reference human sexual differences and psychology, we got a slightly more manageable 2,168. Human sexual differences and biology produced an even more reasonable 33. The librarians said they were sorry that because of costs they could not call up and print out even 33 abstracts on-line, explaining that such an order would have to be printed out off-line by the information retrieval service computer in California and sent to Hanover by mail. "It takes two or three days," they said apologetically.

The reference librarians then pressed upon us all manner of tantalizing adver- tisements about the library's new retrieval systems, by which the computer scans hundreds of indexes and abstracts for you in seconds and spits out your own personalized bibliography. No more grubby, bleary-eyed pawing through ponderous printed volumes.

Visions of bibliographic sugarplums were still dancing in our head as Otto led us off to the circulation desk. There we heard about the latest security measures installed to protect Dartmouth's cherished open- stack system. The books, it turns out, have been bugged. When a book is properly checked out, a librarian deactivates its magnetic insertion, so that it can be carried through the exit gate without setting off the alarm buzzer. The incidence of stolen books has dramatically decreased, according to Otto, since the installation of the new system though, like all systems, it has its kinks. The occasional three-ring binder, belt buckle, or Afro comb, inexplicably magnetized, will set off the alarm. So far such problems have almost all been easily solved by running the offending metal article through the deactivating machine as though it were a book. "Except for that damned flute," muttered one of the student workers who overheard our conversation.

From circulation, we were shepherded along to the office of Director of Automated Services Emily Fayen, whose door was cryptically labeled "Pilot Project." This project, about which Otto is very excited (and Fayen is ecstatic), is an experimental on-line cataloguing program designed to introduce Dartmouth's library patrons to the idea of using a computer to locate items in the library. It replaces the old familiar card catalog with a small computer terminal and video screen though Fayen is emphatic about the fact that the library does not intend to go whole hog online until there is sufficient evidence that the library's faculty and student users are happy with the idea. Dartmouth has been dual-cataloguing its acquisitions since 1972 (with an obvious eye toward someday switching over entirely to computer- cataloguing and video-screen call-up). Some 350,000 citations have already been put on tapes in machine-readable form as well as on index cards in the ordinary way.

We asked Fayen the usual question about a computerized catalog "What about when the computer goes down?" and got the reassuring answer that the system being considered is one with a maximum down time in a worst-case failure of 15 minutes. What that really means, we were told, is more or less a two-computer system, rather like the backup generating system in a hospital.

We went back to Otto's elegant little paneled office on the first floor and talked some more about why she likes being here. Dartmouth, she said, has a delightful combination of smallness and quality. "It's unique," she pointed out, "in having a research-quality library and a student body that is primarily undergraduate." She showed us the 1978-79 Association of Research Libraries statistics, and, sure enough, Dartmouth is the only one of the 110 members which offers graduate degrees in a single-Aigii number off fields (9). And yet, while its 1,347,738 volumes do not, of course, come close to Harvard's leading 9,913,992, they do constitute a full- fledged primary-source research collection.

Otto likes the relative smallness Qf Dartmouth's library because it allows her to steer clear of the bureaucratic tangles that inevitably accompany large library systems and because she thinks it will aid her in creating a library administration which relies even more heavily than in the past on full staff involvement in major decision- making.

Of course, all is not roses, even at Mother Dartmouth. There are problems, the most pressing among them space and money.

"We are totally out of space at Baker and Sherman, and we are approaching capacity rapidly in all the other branches on campus," said Otto. "We simply cannot continue to grow at the same rate as we did during the last decade. Library costs are ahead of even double-digit inflation. Journal literature alone increased in cost last year 16 to 20 per cent and that's only the cost of continuing the journals we already have, without adding any new ones. Books are up 10 to 12 per cent, and we also have problems in maintaining our foreign- language acquisitions because of the devaluation of the dollar."

Libraries across the country all have the same problems of space and money, explained Otto, which make expansion almost out of the question. Otto feels that the task before her is maintenance: "My job," she said earnestly, "is to maintain the quality of the library at the level to which Dartmouth's faculty and students have become accustomed."

HAVE you ever thought deeply about the derivation of the word comedy? Is it from the Greek word for a wild revel, or the Dorian word for a village, or the word for sleep, because comedy is born from night fantasies? It doesn't matter, because all the words are related to a common root that has to do with lying down in an open space." Visiting Professor Erich Segal

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Triumphant Failure

October 1980 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Article

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Article

-

Article

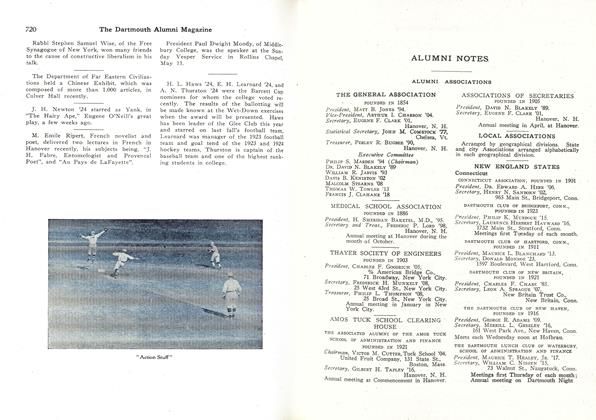

ArticleAMOS TUCK SCHOOL CLEARING HOUSE

June 1924 -

Article

Article"HECTIC BUT STIMULATING"

August 1924 -

Article

Article1925 Bequest Program

July 1950 -

Article

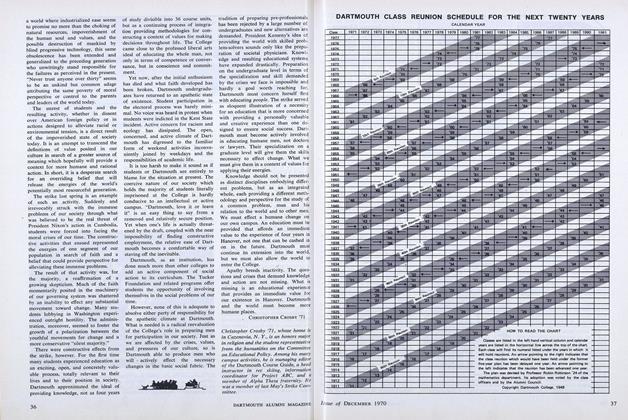

ArticleDARTMOUTH CLASS REUNION SCHEDULE FOR THE NEXT TWENTY YEARS

DECEMBER 1970 -

Article

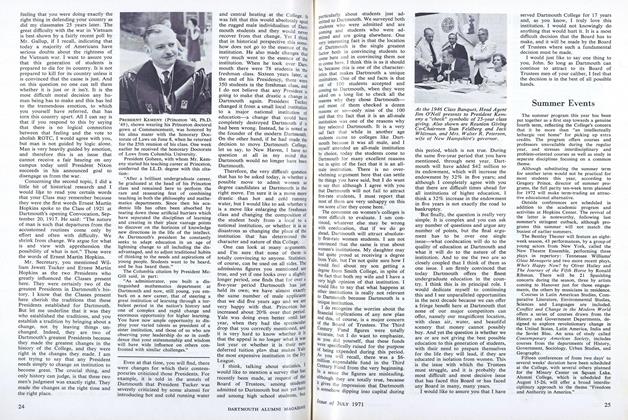

ArticlePRESIDENT KEMENY (Princeton '46, Ph.D. '49),

JULY 1971 -

Article

ArticleJapan's Greatest Family

January 1940 By Warren E. Montsie '15