Notes on a Distinguished Defendant and the Supreme Court’s Great non-decision

DEC. 1977 R. H. R.Seldom in our generation has a legal case so sharply yet so confusingly polarized public opinion as the Bakke case. In the face of the issues it presents, our neat, traditional labels liberal, conservative, radical, right wing, left wing blur and blend and, ultimately, fail as individuals and organizations take their positions on all sides of the issues. Ironies abound; among the record number of amicus curiae briefs before the Supreme Court are two in which, for instance, the American Bar Association and the National Lawyers Guild find themselves in un- accustomed and no doubt uncomfortable agree- ment. Amid the swirl of controversy which has made “reverse discrimination” a household phrase only one thing seems certain: The issues to be resolved in this case are of almost in- calculable enormity not just for higher educa- tion but for the whole developing social fabric of America.

Though constitutional lawyers and jurists must argue the Bakke case in terms of legal con- cepts, from inside academia the issues tend to translate themselves into a less legalistic but no less pressing question. Should higher education operate on its traditional “color-blind” princi- ple, open to all qualified comers regardless of race, creed, or color; or should it indeed, may it undertake special, compensatory, so-called “affirmative action” programs which, over- simplified, tend to discriminate for minority students in order to overcome the long- entrenched discrimination against them? Or in the language of Charles E. Odegaard '32, should universities adopt the stance of merely “recep- tive passivity” toward educating minorities, or should they institute “positive action” (as most have already done) to recruit, admit, and (if necessary) specially train minority students?

Odegaard, president emeritus of the Univer- sity of Washington, has recently published a book in which this question predominates: Minorities in Medicine: From ReceptivePassivity to Positive Action, 1966-76 (New York, The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, 1977. 164 pp. $4.00). On the face of it a book Odegaard calls it a “report” which records the progress made in educating minority students in medical schools during the past decade, it would seem of compelling interest only to those who teach in and administer our medical schools or other professional schools. But in fact its contemporary relevance extends well beyond its self-imposed limitations. For in part at least it also records the gradual conver- sion of an informed, experienced educator.

Upon his assumption of the presidency of the University of Washington in 1958, Odegaard found himself in full agreement with the univer- sity’s commitment to the main-stream, traditionally liberal “color-blind principle” which offered “equal opportunity without regard to race, creed, or color, to all persons.” It was the commencement of June 1963 that first shook his confidence. “As the long line of graduates filed by,” he writes, “it dawned on me that despite the presence of a black community hardly two miles away and despite the talk about the expansion of opportunity for blacks in our society, there were remarkably few blacks among the graduates. I asked myself, since the university is presumably open to them, why were there so few?”

That initial question led to further questions and thence to “a whole new learning ex- perience” during which Odegaard came to realize, he says, that despite all the rhetoric the most striking fact was not how much but how little the academic community had been able “to open a predominantly white educational institu- tion to a minority group.” And ultimately he came to understand, he writes, how fundamen- tally and “how much we must change our perceptions about the educational process in general, if it is to provide real equality of oppor- tunity. ...” Based on his new-found convic- tions, Odegaard took the next logical step: the establishment of special, compensatory “affir- mative action” programs at the University of Washington.

Not inappropriately, in 1971 the first court test of the legality of such programs was oc- casioned by Odegaard’s own policies. In the now famous DeFunis case Odegaard, as president, was named defendant by the plaintiff, Marco DeFunis, who alleged that because he was denied admission to the University of Washington Law School jyhile less well qualified minority students were accepted, his right to equal protection under the law had been violated. With the DeFunis Case case “reverse discrimination” slipped into not only the legal lexicon but the general vocabulary. But the issue remained unresolved, for in 1974 in what has been wryly called its “great nondecision,” a 5-4 majority of the United States Supreme Court decided in effect not to decide the case. Thus the matter was left hanging. And thus the crucial significance of the Bakke case.

Thus, too, some of the significance of Odegaard’s book, which owns the distinction of having been quoted in several amicus briefs now before the Supreme Court. Some of the significance, but not all. For in the years since that starkly white commencement of 1963 Odegaard has come full circle. His position is unequivocal: “I am identified,” he writes, “and myself identify with the idea that ‘business as usual’ is not a sufficient response to the needs of educationally disadvantaged students.” What is required now, he concludes, is “something more . . . something positive in Federalese, something ‘affirmative’ in the way of remedial, compensatory, or preferential oppor- tunity to help minorities to catch up with the majority so that they can participate ultimately on an even basis with the majority.”

Whatever one’s own position, whatever one’s own perplexities about reverse discrimination, Odegaard’s position demands thoughtful con- sideration. He is by profession a historian, by choice a long-time university administrator, by training an informed and conscientious academician, and by inclination a thoughtful man. And unlike many of the rest of us, he is totally committed and unperplexed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

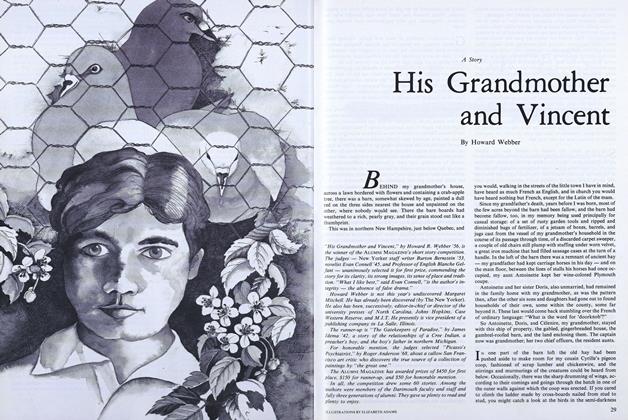

FeatureA Story: His Grandmother and Vincent

December | January 1977 By Howard Webber -

Feature

FeatureThe Well-Tempered Synclavier

December | January 1977 By Woody Rothe -

Feature

FeatureReflections on an $8-million post office The Hopkins Revolution

December | January 1977 By Henry B. Williams -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

December | January 1977 By S.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

December | January 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Sports

SportsThe Coach Departs

December | January 1977 By Brad Hills ’65

R. H. R.

-

Books

BooksNotes on a launching: a new journal, not for the literati alone, but for the literate, one and all.

September 1978 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksNotes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief.

March 1979 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksWood Butchers

June 1981 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksNot for Art's Sake

APRIL 1982 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksSleuthing

APRIL 1982 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksMan in the Cambric Mask

JUNE 1982 By R. H. R.